- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Chapter 17

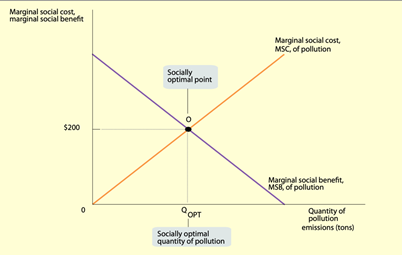

The marginal social cost of pollution is the additional cost imposed on society as a whole by an additional unit of pollution.

The marginal social benefit of pollution is the additional gain to society as a whole from an additional unit of pollution.

The socially optimal quantity of pollution is the quantity of pollution that society would choose if all the costs and benefits of pollution were fully accounted for.

An external cost is an uncompensated cost that an individual or firm imposes on others.

An external benefit is a benefit that an individual or firm confers on others without receiving compensation.

Pollution is an example of an external cost, or negative externality; in contrast, some activities can give rise to external benefits, or positive externalities. External costs and benefits are known as externalities.

Left to itself, a market economy will typically generate too much pollution because polluters have no incentive to take into account the costs they impose on others.

In an influential 1960 article, the economist Ronald Coase pointed out that, in an ideal world, the private sector could indeed deal with all externalities.

According to the Coase theorem, even in the presence of externalities an economy can always reach an efficient solution provided that the transaction costs—the costs to individuals of making a deal—are sufficiently low.

The costs of making a deal are known as transaction costs.

The implication of Coase’s analysis is that externalities need not lead to inefficiency because individuals have an incentive to find a way to make mutually beneficial deals that lead them to take externalities into account when making decisions.

When individuals do take externalities into account, economists say that they internalize the externality.

Transaction costs prevent individuals from making efficient deals.

Examples of transaction costs include the following:

- The costs of communication among the interested parties—costs that may be very high if many people are involved.

- The costs of making legally binding agreements that may be high if doing so requires the employment of expensive legal services.

- Costly delays involved in bargaining—even if there is a potentially beneficial deal, both sides may hold out in an effort to extract more favorable terms, leading to increased effort and forgone utility.

Policies Toward Pollution:

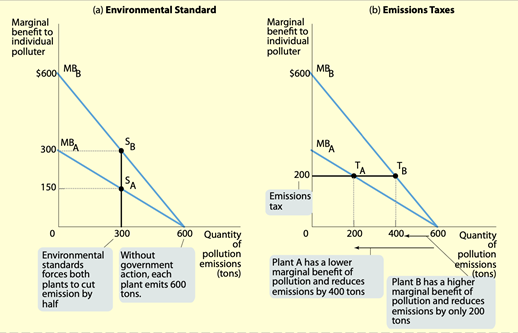

- Environmental standards are rules that protect the environment by specifying actions by producers and consumers. Generally, such standards are inefficient because they are inflexible.

- An emissions tax is a tax that depends on the amount of pollution a firm produces.

- Tradable emissions permits are licenses to emit limited quantities of pollutants that can be bought and sold by polluters.

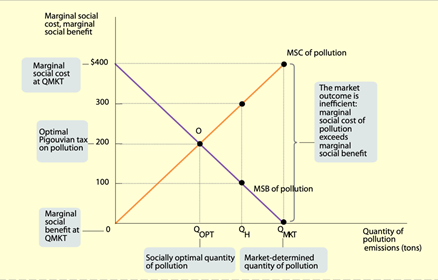

- Taxes designed to reduce external costs are known as Pigouvian taxes.

When the quantity of pollution emitted can be directly observed and controlled, environmental goals can be achieved efficiently in two ways: emissions taxes and tradable emissions permits.

These methods are efficient because they are flexible, allocating more pollution reduction to those who can do it more cheaply.

An emissions tax is a form of Pigouvian tax, a tax designed to reduce external costs.

The optimal Pigouvian tax is equal to the marginal social cost of pollution at the socially optimal quantity of pollution.

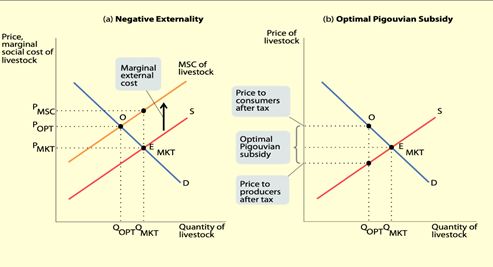

When there are external costs, the marginal social cost of a good or activity exceeds the industry’s marginal cost of producing the good.

In the absence of government intervention, the industry typically produces too much of the good.

The socially optimal quantity can be achieved by an optimal Pigouvian tax, equal to the marginal external cost, or by a system of tradable production permits.

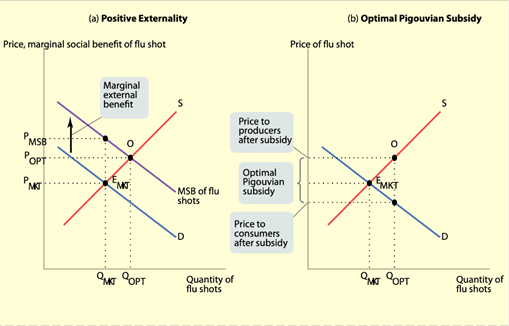

The marginal social benefit of a good or activity is equal to the marginal benefit that accrues to consumers plus its marginal external benefit.

A Pigouvian subsidy is a payment designed to encourage activities that yield external benefits.

A technology spillover is an external benefit that results when knowledge spreads among individuals and firms. The socially optimal quantity can be achieved by an optimal Pigouvian subsidy equal to the marginal external benefit.

An industrial policy is a policy that supports industries believed to yield positive externalities.

The marginal social cost of a good or activity is equal to the marginal cost of production plus its marginal external cost.

A good is subject to a network externality when the value of the good to an individual is greater when a large number of other people also use the good.

Any way in which other people’s consumption of a good increases your own marginal benefit from consumption of that good can give rise to network effects.

A good is subject to positive feedback when success breeds greater success and failure breeds failure.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|