- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Introduction to Shudda-advaita Darshan 1 страница

Introduction to Shudda-advaita Darshan

as per Tattvarth-Deep Nibandha

and Anu-Bhasya

Contents

Introduction to Shudda-advaita Darshan as per Tattvarth-Deep-Nibandha

Summum Bonum of life:

Pramana Chapter:

Pramey Chapter

Samkhya System Nirakarana:

Atomic Theory Nirakaran (Paramanuvaad):

Buddhist Theory Nirakaran:

Vigyanvaad Nirakaran:

Syaadvaad Nirakaran:

Mimansakas and Naiyayikas Nirakaran:

Mayavaad Nirakaran:

Nescience (Avidhya)

Relation between Jiva and Brahman:

Work, Knowledge and Devotion:

Summum Bonum of life:

Tattvarth Deep Nibandha is one of the works of Shree Vallabhacharya, the exponent of the Shuddha-advaita system of Philosophy in India. His Philosophy of Shudda-advaita is explained at great length in his work Anubhasya, which is a commentary on the BrahmaSutras of Badarayan Vyas. In his Subodhini commentary on the Bhagwat, he has explained this philosophy also. His son Vitthaleshji and his descendents, Shri Purushottamji, Yogi Gopeshwarji, Girdharji, Murlidharji etc. also have explained this philosophy both by their learned commentaries on his works and also by their independent works. In all these works, has been discussed the problem of ultimate reality of the world and the summum bonum of life.

Every philosopher in every age has tried to solve this problem according to his light. In this world, the end of all activity is happiness. There is not a single person in this world who will welcome pain. Even those persons who commit suicide do so only out of utter disgust in life. When all hope of release from pain deserts them, they are compelled by circumstances to resort to suicide. But in their heart they desire happiness. One writer has said that all men by their nature desist from pain. Every one desires happiness. Shri Vallabhacharya, in his commentary Subodhini while explaining the purpose of life says ‘To all, two things are desirable –

1. Removal of pain

2. Attainment of happiness”.

Mere removal of pain is a negative side of the problem. So the attainment of happiness is also necessary. The Greeks called this happiness ‘well-being’.

That the highest human good is the well-being is universally admitted by all philosophers all over the world, both by the past and the present but there are different views to precise nature of well-being. Mr. Rogers in his ‘A short History of Ethics’ writing on this question says ‘the vulgar often identifies it with pleasure, wealth or honour, but these cannot be final ends, for some pleasures are not desirable, Wealth is only a means to well-being and honour is sought rather to increase our confidence in our own virtue then as an end desirable for its own sake. Plato pronounced the doctrine of an absolute good which is the prime source of the excellence of all good things. This also must be rejected because it is contrary to experience. The Cynics held that wellbeing is identical with the possession of virtue. This also cannot be accepted as final, since the worth of virtue has to be estimated by the nature of the mental activities to which it leads.

Moreover, regarded as a merely inactive possession, it is useless and almost meaningless. Aritotle defines ‘well-being’ as an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue in a complete life. This implies that as ‘well-being’ is not a subordinate end, it must be complete. It is an unconditional good, desirable for its own sake, and preferable to any other. Again, it implies that this activity must be conscious, and either purely rational or in obedience to pleasure. The Epicureans identified happiness with pleasure and Stoics with abstinence from it and life of complete selfabnegation. This is a how the problem of ‘well-being’ was solved by the Greek Philosophers. Latin Philosophers gave a new colour on this.

Hobbes understands ‘well-being’ in self-interest, in constant progress of desires towards of fulfillment. According to Spinoza, ‘well-being’ consists in ‘the knowledge of God’, who is the one substance embracing all reality within HIS own being. Butler and August Compte saw wellbeing in social good or altruism. According to Kant, distribution of happiness, in exact proportion to virtue constitutes Summum Bonnum. The German philosopher Fichti, Schelling and Hegel were rationally idealists. To them well-being meant freedom by the knowledge of self. The Utilitarian school of Bentham and Mill, which is described by Sidgwick as ‘Universalistic Hedonism’ defines well-being as the greatest happiness of the greatest number in society. According to this, the value of any kind of happiness is to be judged from its utility. From all these views, we learn that in the Western Philosophy, the problem of well-being is pursued variously by various philosophers. However all accept well-being as the supreme end of the life. It is either individualistic or universalistic. The Individualistic well-being is called Egoistic Hedonism. It teaches that the agent must, or ought to pursue, his own happiness. Thus latter is called universalistic Hedonism, which regards universal happiness as the end. Only the German school of rationalistic idealism sees happiness in the freedom by knowledge.

Now let us turn to the East. The earliest school that has attempted to tackle this problem, systematically is the Samkhya school of Kapila. According to this school, Summum Bonum is freedom from pain. Pain is threefold: -

1 The Internal (Adhyatmik)

2. the External (Adhibhautik) and

3. the Divine or superhuman (Adhidaivik).

Of these the internal is two fold – bodily and mental. Bodily pain is caused by the disorder of the universal humours, wind, bile and phlegan; and mental pain is due to perception of particular objects. The external pains are caused by men, beasts, birds, reptiles and inanimate things. The superhuman pains are due to the evil influence of planets spirits, good etc. Release from all these kinds of pains is the end of human life. That constitutes final beatitude. The spirit experiences pain on account of its being under the influence of nature. If the spirit isolates itself from the influence of nature, it becomes free from pain. So spirit’s isolation from nature is the liberation according to the Samkhyas. When the spirit realizes the real character of the nature, it ceases to operate its influence upon him. Pantanjali said that the means of freedom from pain lies in the exercise of control over mind and senses. It is the want of control over these that is the cause of all troubles in the world. The logicians (Naiyayikas) assert that the knowledge of right kind which enables a man to discriminate what is ephemeral from what is permanent can help him to secure liberation from pain. That is the view of the Vaisheshika also. The Naiyayikas lay emphasis upon correct knowledge, arrived by logical methods of perception, inference, analogy and the verbal authority. The Vaisheshikas require the knowledge of seven subjects such as substratum, quality etc. which will explain the real nature of the things in the world. Jaimini required performance of sacrifice as a means to the liberation of Pain. Badrayan, the author of Brahman Sutras indicated the knowledge of Brahman, the supreme spirit for the achievement of the above end. Buddhism sees a means in self-effacement and Jainism in self-control and penance. To Shankaracharya, liberation is the removal of nescience by means of the knowledge of Brahman. Ramanuja couples the knowledge with work for that end. Thus various ways are suggested for liberation from pain by different schools. Vallabhacharya, the author of Tattva Deep Nibandha undertakes here to offer solution from his own point of view. For the sake of convenience, he divides his work into three chapters

1. Shastrarth

2. Sarvanirnaya

3. Bhagwatarth

In the first chapter he gives the interpretation of the scriptures; in the second, his verdict, on the character of the various scriptures, and in the third his exposition of the underlying meaning of Bhagwat.

The first chapter contains 104 verses. On each of these verses, he has written his own commentary called ‘Prakasha’. This elucidates in an explanatory manner, what he has stated concisely and pithily in the verse-part. To make clear the ‘Prakasha’ portion, Shree Purushottamji has written very able and learned commentary called ‘Avran-bhang’ which means breaking or removing of the veil. The obscurity of the thought in Vallabhacharya’s Prakasha is the veil, which he has removed by his commentary.

The first verse of the first chapter, he devotes to the salutation of Lord Krishna, whom he regards as the Supreme Lord. In the second Verse he stated the problem of this work. It is as he says, ‘emancipation. ’ Only the Satvik and the votaries of God are entitled to it. It is for them that he undertakes to consider that problem in this work.

Every philosophical problem should be approached from four points of view viz.

1. Pramana

2. Pramey

3. Sadhan

4. Fal

Here emancipation is the fruit. Its real character should first of all be known by means of proofs. That will come under the Pramana section. Then the question of the main objects of knowledge, worth knowing will be discussed in Prameya Section. Then the various means for the realization of ultimate fruit will be explained under the Sadhana section. In the fruit section, the real nature of fruit will be explained. The first chaper i. e. Shastrath Prakaran deals with the Pramana.

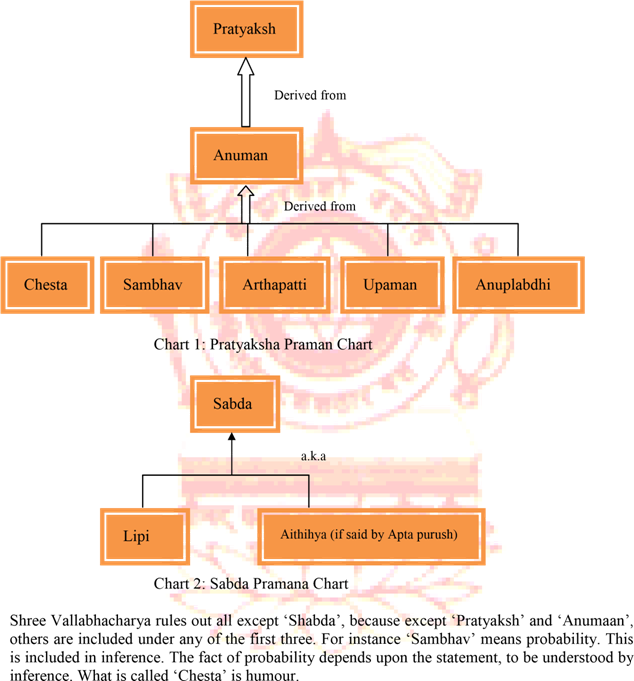

Pramana Chapter:

Pramana means ‘Proofs of knowledge. ’ Pramana is defined as ‘Pramakaran’ – an instrument of knowledge. ‘Prama’ is explained as ‘Yathartha Anubhav’ i. e. it must be direct cognition, free from doubt, perversion of facts or false reasoning.

The ‘Yatharthatva’ of ‘Anubhav’ is explained as ‘Tadvati Tatprakaaratvam’ for instance ‘Rajat’ (Silver) has Rajatva ‘Silverness’. So when we say ‘Rajat’ is ‘Rajatva’, it is ‘Yatharth’ (exact) cognition. The work ‘Karan’ means ‘Sadhaktam Kaaran’ i. e. the cause that is most essential in producing a certain result. So anything that is most essential in exact cognition of the object is called ‘Pramana. ’

Here the question to be decided is what should be our ‘Pramana’ in the right appreciation of our problem of emancipation and understanding the ultimate reality of the world viz. Brahman. In V. 7 Shree Vallabhacharya mentions only ‘Sabda Pramana’ as valid, (“Sabda Eva Pramanam”). The Materialist (Charvaka) recognizes only ‘Pratyaksh’. The pramanas considered by other systems are given in the below table:

| Sr. No | System | Pramanas |

| 1. | Buddhas | Perception and Inference. Not in Vedas (Pratyaksha and Anuman) |

| 2. | Sankhyas | Anuman, Pratyaksha and Shabda |

| 4. | Mimansakas | Arthapatti |

| 5. | Naiyayikas | Analogy(Upaman) |

| 7. | Vallabhacharya | Shabda Only. |

| 8. | Charvakas | Pratyaksh |

| 9. | Jaines | Pratyaksh and Anuman |

| 10. | Vaisheshikas | Pratyaksh and Anuman |

| 11. | Madhavacharya | Pratyaksh and Shabda |

| 12. | Yoga | Anuman, Pratyaksha and Shabda |

| 13. | Ramanujacharya | Anuman, Pratyaksha and Shabda |

| 14. | Maheshwars | Analogy (Upaman) |

| 15. | Kumaril, AdvaitaVaad | Anuplabdhi and Abhav |

| 16. | Puranikas | Sambhav and Aitihya |

| 17. | Tantrikas | Chesta |

|

| ||

Pramana Derivation Chart:

It is mere continuity of a vague assertion of which the original source cannot be traced. It is open to doubt. So when it is open to doubt it is not a valid means of coginition. If however the original source is known and known to be trustworthy then, it is a case of Verbal Cognition (Shabda) Pure and simple. Similarly ‘Aitihya’ becomes a case of Shabda Pramana if it is given by a trustworthy person; otherwise it is no Pramana at all. Pratima when it is a correct word it is included under Pratyaksha and Anuman, otherwise it is not valid.

Thus having ruled out Sambhav, Chesta, Aitihya and Pratima we shall consider Upaman, Arthapatti and Abhav. Upaman means ‘Analogy’. It is illustrated by the example, “As the cow, so the gavaya”. Gavaya is an animal, which resembles a cow. The knowledge of the Gavaya here is got from the words ‘As the cow’. Therefore it is included under verbal cognition. Also here when we first see the animal Gavaya, we at once remember the cow which is seen. So it is perception which is here instrumental in giving us the knowledge that the animal like cow which we see is Gavaya. Or it can be included under Inference. Mr. Ganganath Jha in his translation of Tattva Kaumudi explains it thus –‘When experienced persons use a certain term in reference to a particular thing, it should be regarded as denoting it – specially when there is no function other than direct denotation as is found in the well-known case of the term cow applied to the animal genus ‘Cow’ (Major Premise).

The term Gavaya is used (by experienced persons) in reference to the animal similar to the cow (Minor Premise). Therefore the term gavaya must be regarded as denotative of that animal (Conclusion).

Thus this cognition is purely inferential. So this is rejected. Shri Purushottamji also in his Prasthan Ratnakar rejects it as an independent proof.

Arthapatti means ‘Presumption’. The Naiyayikas reject it because they maintain that its function is performed by a Vyatirekyanuman. The example cited here is ‘Fat Devdutta does not eat by day’. Fatness is the result of eating. Now if the man does not eat by day, he must be eating by night. So ultimately what is called ‘Presumption’ becomes the case of inference. Similarly in the case of latter, although there is not direct contact between the object and the senses, yet there is comprehension of the absence of an object through the medium of Visheshan Vishesyabhav. The absence of the jar, at a certain place itself in the form of vacancy; all faculties with the sole exception of the Sentient Faculty – are consequently undergoing modification and all these diverse modifications are perceptible by the sense; hence there can be no object.

So out of the list of 10 Pramanas, only three remain to be considered, Pratyaksh, Anuman and Shabda. Vallabhacharya believes only in ‘Shabda Praman’. Inference is dependent upon Perception. Inference without help of perception cannot give us knowledge. If the perception is invalid; the inference will be invalid. As inference is subordinate to perception, it cannot be accepted as an independent proof in the matter of the cognition of Brahaman. When we prove the statement viz. the mountain is fiery, we give smoke as its reason. But when we give reason, we remember the cases of smoke always associated with fire. We had perceived on a former occasion smoke, arising from fire. We had perceived all that where there was no fire there was no smoke. We remember this knowledge of perception and with its help prove the case in question. So inference as an independent proof has no value. This being the case in the matter of the knowledge of Brahman it is not accepted. Because it requires direct or indirect contact between the senses and the object to be cognized, Brahman cannot be thus cognized. Moreover perceptual cognition is very often erroneous, due to the defective function of organs. So it is also not accepted.

What is, then, this Shabda Pramana? It is the sentence of a trustworthy man. The word ‘Apta’ excludes all pseudo-knowledge. It should be self-sufficient in authority. All verbal testimony is not accepted as shabda pramana, but only those that lead to the knowledge of Brahaman. Judged by this test, out author mentions only the following four scripture as the testimony – the Vedas, the Gita, the Brahma Sutras, and Samadhi Bhasha of Bhagavata. The Jaimini Sutras are also to be included in this list if they do not conflict with these.

In the Bhagvata, there are three kinds of language. One is ‘Lok Bhasa’ i. e. the language similar to that used by wordly poets like Kalidas etc. The portion which contains description of time, place fights etc treated as ‘Lok Bhasha’ i. e. language similar to that used by wordly poets like Kalidas etc. The portion which contains description of time, place, fights etc. treated as Lok Bhasa. In the Prakasha it is illustrated by the line Athoshasi Pravuttayaam etc., i. e. when it was morning. Such Descriptive passages do not add to the knowledge of Brahman. Hence it is not included in the category of the word proof. The other kind of language is called ‘Paramat Bhasa’ i. e. the language in which the opinions of others are mentioned as in the example of ‘Shrutam DwaipayanaMukhaat’. This was heard from the mouth of Dwaipayana. This has no value for the knowledge of Brahman. Only the portion called Samadhi Bhasha is useful to us, because, in it, the truth, experienced by the author in his state of meditation is depicted. It being so, it can serve as a valid proof. Shri Vallabhacharya explains the word Samadhibhasha as ‘Samaadhau Swaanubhuya Niropitam Sa Samadhibhasa’. Such truth can stand all tests. It can never be errorneous. So in the matter of proofs, Vallabhacharya accepts only Shabda Pramana that which gives us the knowledge of transcendental subject i. e. Brahman and of this only.

The Vedas consists of two parts: - 1. Purva Kanda 2. Uttar Kanda. The former means samhitas and Brahman works, the latter means Aryankas and Upanishads. The subject of the former is Sacrifice and the latter ‘Knowledge of Brahman’. According to Vallabhacharya entire Vedas consisting of the above two parts and also of Arthavada etc. becomes Verbal Recognition. Jaimini will accept only the first part of the Vedas and reject the second as of no use for religious life. Shankaracharya on the other hand accepts only the latter and rejects the former as being useless. But Vallabhacharya accepts both. He does not take Vedas by half. To accept one part and reject another, is nothing but having the Vedas or cutting a body into two parts. In Vallabhacharya’s opinion, both the portions are important and complementary of each other. In all these four works, the principal subject dealt with is Brahman. So whatever doubts we have about Brahman should be solved by these four works. These works are not to be taken as separate proofs. Each succeeding work should be regarded as supplementary of each preceding one. Any doubt arising about any point discussed in any preceding work should be removed by reference to the succeeding work. For example if one, while reading the shruti passage “he is without hands and feet and yet He runs and holds”, has a doubt whether human hands and feet are denied here to Brahman or it is a general denial: then that doubt should be solved by a passage of Gita viz ‘He has hands and feet etc. every where). Similarly if doubt arises from the passage of Gita, it should be removed from reference to the Sutras of Badarayan and any doubt in that should be cleared from reference to Bhagavat.

The manusmriti and other Smritis are also authentic if they are not contradictory to the spirit of the Veda. But if it is asked, what should be done if there is in some portion inconsistency and in some contradiction. In that case our author says that it should be rejected. Anything contrary to the meaning of Vedas should be discarded.

Having mentioned the names of scriptures which he accepts as proofs of verbal cognition; Vallabhcharya says that all these works are unanimous in character in the matter of the knowledge of Brahman. Their principal meaning is God, the highest entity. That God is represented under various names in these works. In the Purva Kanda of the Vedas, He is represented as ‘Sacrifice’ in the Uttarkand as Brahman, in the Smriti works as Parmatman and in Bhagvat as Bhagwan or Krishna. These different names do not imply different Gods. God is one but is comprehenced differently. Work and knowledge are the powers of God. He reveals his power of works through sacrifice which is God’s form. The power of knowledge is revealed through his form of Brahman. As the Purva Kanda of the Vedas reveals only sacrifice – as part of God, it is partial revelation of the conception of God. Similarly the Uttarkand is partial, being confined only to be knowledge-aspect. But Bhagvata exhausts the full conception of God: - the work-aspect as well as knowledge-aspect. It is therefore complete exposition of God. In that work, God’s manifold sports are described exhaustively. So to understand the real conception of God, it is necessary that we should consult the Bhagwata without which our knowledge of Brahman will be only onesided. The Vedas consider God analytically but Bhagvata considers it synthetically. It says that God is capable of assuming many forms. Everything that we see is God. Nothing exists outside God. So even sacrifice and knowledge aspects are not separate from God. They both exist in him. Thus the conception of God is considered synthetically by the author of Bhagwata. So for thoroughness in the comprehension of God, we must betake to Bhagwata. It cannot be dispensed with it. No doubt Gita and Brahman Sutra give the knowledge of Brahman; but they do not describe the bliss parts of God. For this reason Vallabhacharya adds Bhagwata to the list of the verbal proofs. Shankaracharya accepts only the Vedas, Gita and Brahma Sutras, but Vallabhacharya is not satisfied, with these three only. So to make the list complete, he adds Bhagvata.

In these scriptures three different means for reaching God have been mentioned. In this section, Vallabhacharya only gives a cursory glance of them. He reserves them for detailed discussion in the second section. The three names are work, knowledge and devotion. Ordinarily they are supposed to be different means Vallabhacharya also regards them different, but he says that their ultimate goal, when considered in their real light is one and the same. Jaiminiya lays stress upon work only as the path to reach summum bonum and Shankaracharya upon knowledge only. Ramanujacharya harmonises both these into only conception of workship. The teachers of the Devotional sect regards devotion as the only proper means. Thus divergent opinions prevail among the philosophers and thinkers regarding the adequate means of reaching God. Each school sticks to one particular means, which it considers to be the best of all the means. According to Vallabhcharya, each of these means should be harmonized with others, for the thorough comprehension of God. Each one taken separately is not sufficient to enable man to march onwards on the path of spiritual progress. Moreover for the right understanding of any thing, we must look at it from two points of view, externally and internally. The external view will reveal the object only superficially i. e. only the outside of it as it appears to the external senses will be known. This can be known when the object is viewed intrinsically. Our conceptions of work, knowledge and devotion should be viewed from both the sides. Mere internal view will not be adequate to give us complete truth. To say that only work is good, or knowledge is good does not give us the whole truth. The advocates of work or knowledge or devotion did not look at the problem internally.

Hence they have erred in their judgement in regarding the particular means which they advocated as par excellence. Vallabhacharya examines the problem, internally. In his examination, he finds that really speaking there is no contradiction between these means. The contradiction that appears to us is only apparent, not real, because we look at the problems, from one angle of view i. e. from external view. But if we look at them from the other view, we shall understand their real nature and then the apparent contradiction will at once disappear. So, in Vallabhacharya’s judgment these three different means can be synthesized into one. Really speaking if we speak of our life in terms of geometry, then it should be conceived as a triangular figure-having three sides of work, knowledge and devotion. These sides must meet each other at their ends where the sides cease to exist separately. They are absorbed in making a figure called a triangle. In other words work, knowledge and devotion are necessary to make life. These three concepts should be merged each other into another. So that life is not this or that, but sweet harmonious amalgamation of all these-which will form one means of reaching God. Although Vallabhacharya has soft corner in his heart for devotion, he does not disregard other two. In verses 20-21-22, he explains the real meanings of work, knowledge and devotion. In ‘Gyannishtha Tada Gyeya Sarvagyo Hi Yadaa Bhavet. ’ He explains the real nature of knowledge. What is knowledge? Is it one derived from pondering upon the sentence “Tatvamasi” etc.? No, such knowledge cannot reveal Brahman. It can simply give verbal knowledge but cannot reveal God. God is the ultimate goal of each means. If knowledge is unable to take one near God, it is useless. It is not worth its salt. The end of knowledge will be secured, if the knower has become possessed of the knowledge of all i. e. God. He must through knowledge realize the fact that in all objects there is only one thing. And that thing is God. The different objects that we see are His diverse forms. Behind these diverse forms, there lies the supreme entity of God. When one realizes this fact i. e. sees unity in the midst of diversity, is said to have got real knowledge. So in short, knowledge has its value if it enables one to realize the unity. Otherwise it is useless. It must make the knower understand that God is omnipresent. It brings home to our mind that He is everywhere. Such knowledge is necessary for one’s seeking God. Similarly work is not mere sacrifice and the rituals. His idea of work is explained in the line ‘Dharmanistha Tadaa Gyeya Yadaa Chittam Prasidati! ” When the mind of the person becomes calm we must know that he has got the real sense of work. According to this view, the test of Dharmnistha lies in its being capable of making a man’s mind pacific and calm under all circumstances. Things might go wrong with him. The world may behave inimically towards him. All his hopes may fail and his plans may go amiss yet his mind remains cool and pleased. Its equipoise is never disturbed. The various distractions and troubles of the world will simply pass over the surface of the mind, but will not affect it even in the least. When the mind is so cultivated, it is said to have acquired the real purpose of work. One who acquires such an attitude of mind sees the hand of God behind all the worldly events. He will regard the world as theatre in which God enacts various scenes. Himself assuming various forms in order to play the role of various characters. So the happiness or misery, joy or sorrow, profits or losses have no meaning at all.

These are the external changes. This being the conviction of one devoted to the ideal of work, he never lets his mind ruffled. Tranquility and placidity is the test of the ideal of work. This is the underlying meaning of work. Such an ideal has its place in life. It is essential like knowledge.

Similarly the ideal of devotion is essential. But it is not simply ‘love’. It connotes a great deal.

He explains it in the line ‘Bhakti Nishtha Tadaa Gyeya Yadaa Krishnah Prasidati”. When Krishna is pleased, the ideal of devotion should be supposed to have reached completion. The test of knowledge if Sarvagyata (knowledge of all) that of work “ChittaPrasannata” (Placidity of mind) and that of devotion, KrushnaPrasannata (grace of the Lord). If the knowledge does not conduce to the state of knowing God in all things, it is of no use. If the sacrifices etc. which we understand as work, do not free the mind from passions of greed etc. and make it placid, then they are not worth their salt. The Ultimate object of work is to make a man resort to the service of God. The devotion has its value only if through it a man becomes recipient of the grace of God. These are the three ideals of life, though treated separately, but really speaking they are one. They are rather stages on the path to reach god. The stage of knowledge is the first one, that of work(services) is second one, and that of devotion the third one. That is why Vallabhacharya mentions knowledge first in his Karikas. His message is that a devotee should cultivate all these ideals to perfection in order to reach the Summum Bonum. These three ideals must be merged one into another, to evolve out of that merging a new beautiful life of a devotee. So according to him, nothing among these ideals is antagonistic to each other. In other words the merging of life of a devotee is the complete ideal of the knowledge, work and devotion into each other. But these ideals should be understood in their real significance which are conveyed in ‘Sarvagya, Chittaprasannata, and KrishnaPrasannata”. In the absence of the fusion of these ideals, his life should be understood as ‘Imperfect’ and our author brings home to our mind by pointing out the futility of these separate ideals. In the Prakash, he explained this point by saying that just as a man who wants to cross the river must throw his body into it otherwise he cannot cross it, so also, one must throw one’s whole heart and soul into the realization of these ideals otherwise the end for which the ideals are meant will not be secured.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|