- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Boots. Slippers. Low boots

SEP 23, 2020 AT 8: 00 PM

Boots

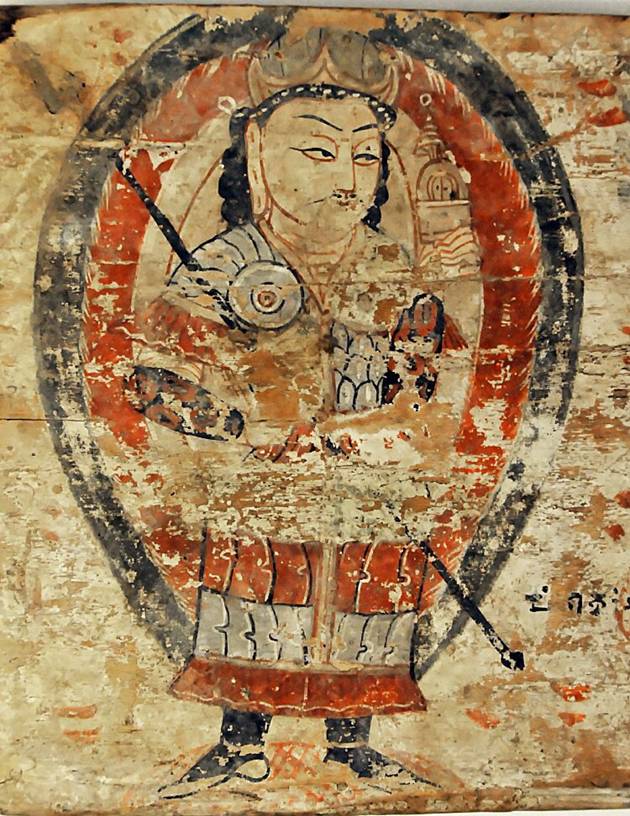

Title image: leather boot from Mount Mugh, now in the Hermitage in St Petersburg. Photo: Mesteller Janos

The first thing I tell new re-enactors to get is a set of footwear. Many western re-enactors leave footwear to the end, as there's presumably good evidence for going barefoot in medieval Europe, but the same cannot be said for early medieval Central Asia - a barefoot person is only seen once, in a farming context, and all his coworkers wear boots. In fact, going around barefoot was considered bad etiquette according to Sasanian customs, and perhaps the same could be said for Sogdiana.

There are two types of boots worn in Sogdiana - tall boots extending to the knee, and shorter boots extending just above the ankle. From the 6th - 7th Century site of Yakke Parsan in Khwarazm, a third type of footwear is known, which is a simple low slipper. Shoes were made on a wooden last (a mould for making shoes), as evidenced by the find of a last from Munchak Tepa.

Slippers

The shoe from Yakke Parsan, from Nezarik " Raskopki Yakke-Parsana, " in " Materialy Khorezmskoi Ekspeditsii 7"

Only one slipper has survived, and it comes from the 6th - 7th Century site of Yakke Parsan, in Khwarazm. In its shape, it appears quite similar to the textile footwear from the Astana Cemetery, Tang China, but is made of leather instead of textile or hemp. It appears to be made in two parts - a sole, and an upper, with a seam at the back. Slippers aren't shown in any Central Asian painting or iconography, so it's unclear how these might have been worn, but parallels can be drawn to paintings from Dandan Uiliq, where white slippers with ties around the ankle are worn over taller black footwear, possibly made of fabric (like the few surviving socks and stockings that have survived from early medieval Central Asia) or a softer, thinner leather.

Low boots

Two examples have survived, one from Mount Mugh, and one from Kafir Kala near Samarkand, and both show the same sewing pattern. The boot from Mount Mugh is on display in the Hermitage, and many aspects of its construction can be seen clearly.

The following photographs have been provided thanks to Mesteller Janos:

There's a few interesting details in the construction.

First, and perhaps most interesting: this isn't a turnshoe - the seam connecting the sole to the upper hasn't been stitched inside out and flipped. In fact, thread is just about visible going all around the foot.

This is similar to a set of boots found in Mongolia, dating to the 4th - 6th Centuries, which are again low boots, published in Seregin et al, " Скальное Погребение Урд Улаан Унээт (монгольский Алтай): Возможности Культурно-хронологической Интерпретации"

Secondly, the boot is made up of many parts. Just going off the photos, there is: a sole; an upper, which simply covers the dorsal aspect of the foot; a heelpiece, which appears to be roughly triangular; the main tube of the boot which rises up the leg; and a narrow vamp connecting the upper to the main tube.

Using multiple parts, each of which could be shaped and fitted, must have made construction and fitting the boot easier.

Who wore these? Sogdians normally wear long clothes that extend to the mid-shin, so it's often hard to see how tall their footwear are, but there are three groups of people who definitely wear these shorter boots - wrestlers, dancers (sometimes), and acrobats, who might have benefitted from the added mobility of short, wide boots, compared with taller narrow boots

Wrestlers on the western wall of Panjakent XVII / 14. From Belenitsky, Монументальное искусство Пенджикента

A rhyton in the form of a female acrobat. From Marshak and Baulo, " Silver rhyton from the Khantian sanctuary"

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|