- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

of the Celts 5 страница

In Ireland, the division into the three classes as on the mainland in Roman times had survived. The druids were called Draoi, Ovates were the Faith and later called Fili, possibly deriving from the Latin filius, and the bards also were called Bards. When the Druids were later disqualified by Christianity, they disappear from the reports. Many of their tasks were taken over by the Fili, who, of course, now no longer could officially perform their original activities like the sacrifices and rituals for the gods, but were able to maintain their position in society as philosophers, poets of the courts, scholars and advisors to the kings. They could preserve their tradition and certainly further carried out secretly many practices of the old religion. The bards but mostly lost the religious background and became just wandering poets, storytellers and musicians.

The education of a File as testified by the ancient Irish records lasted twelve years. The substance of the first year was related to grammar, twenty memorized stories, and the Ogham tree alphabet, to which I shall return. Over the next four years, every year ten more stories had to be learned by heart, plus a dozen hours philosophy, the law of privileges and other poems, up to the sixth year it had to be a total of forty-eight poems and twenty stories. After another three years, the student was given the title Anruth, which could be interpreted as "noble river", apparently alluded here to the flow of inspiration and poetry. The outward sign of this was the presentation of a silver branch. Until then, he had learned another fifty stories, so he now had a repertoire of in total one hundred and seventy stories. Furthermore, he had learned to write praise-poems and treatises on a subject as well as the laws of rhyme and style in the Irish language, which is a very complicated matter, poetic composition and history of the place names in Ireland. After the tenth year and the completion of composition and poetic form he was called Eces, which means "man of learning". After the eleventh year, in which he had memorized additional hundred poems, he received the title File, which meant that he was a full-skilled poet. After the twelfth year, and one hundred and twenty other eulogies he was appointed Ollamh, Doctor of poetry, and received as an honorary token a golden branch. These branches (in the first year he was awarded one of bronze, then of silver and in the end the golden one) had little bells and were attached to the garment so that everyone was aware in the hall, when the File entered to tell a story or to recite a poem.

Within these schools there were also special studies offered, which resulted in being an adviser of kings, a jurist or a doctor. But a longer training period was necessary for this education, which could have approached about twenty years as mentioned in classical literature. From the tradition is also clear that all of these tasks were not reserved for men. There were, as already mentioned in ancient records, female Druids such as those pointed out by classical authors on the island of Sena opposite Armorica, or in the Irish myths, the beautiful Fedelma in the Táin bó Cuailnge, who foretold to Queen Medhbh a war with many losses, and old Leborcham, a satirist and educator of the beautiful Deirdre, who was quite familiar with prophesies. Even female doctors and poets are mentioned, not only in the legends, but also in the collection of the Irish Brehon Laws, which were written down in the fourteenth century, but which are, for the most part, however, are much older.

Some other druids who are named in the legends in particular, are Cathbad, the druid of King Conchobar of Ulster, Mog Ruith, the inventor of a vast, dangerous magical wheel, which could kill or blind the enemies, and who was even said to have taken off into the air with the support of a cloak of bull-fur, bird wings and Druidic device, or Dian Cecht, the physician of the Tuatha dé Danann, the People of the Goddess Danu, who healed with herbs, spells and sacred springs.

To the druids of Ireland were the foundations of their world-view the immortality of the soul, the migration of the soul, nature observation, time calculation and a philosophy of life, in which everything was imbued with the divine. But they are said also to have performed weather magic and the drying of rivers, and to have exercised immense power with their spoken magic. A Druid could, for example, kill or dispose with his curses a king who appeared to him no longer suitable for this position. In the old Irish literature there are some examples of such maledictions: before the battle of Moytura proclaimed the druid of one party towards the other: "I will put the heaviest curse on them, tell satires against them and bring disgrace on them, so that they cannot resist our warriors because of my magic formulas."

A description of a corresponding magical incantation is found in the book of Ballymote. It had to be carried out on a hill after a fasting period: "All stood with their back against a hawthorn bush. The wind was blowing from the north. Every one took a sling-stone and a hawthorn branch in his hand and sang his verse to curse the king over it. Then each one placed the stone and the branch on the roots of the hawthorn. If they were at fault, the earth opened beneath them to devour them. When in the contrary the king was wrong, he was together with his wife, son, horse, weapons, equipment and dog swallowed up by the earth of the hill." As it is quite unlikely that such spectacular incidents took place, yet could the suggestive, psychological impact of a magical curse be substantial and could indeed be dangerous for the position or life of a king.

The so-called bardic schools existed until the 17th century, but in them only a remnant of the formerly long training was taught, namely poetry, the intricate rhymes system, harp-playing, genealogies and stories of kings and the myths of the ancient gods, now called fairies and heroes. The students had to endure for days in windowless, dark rooms with a stone on the chest, until they received the inspiration for their poetry.

The meeting place of the druids in Ireland was Uisneach, which was believed to be the center of the country. In the ancient scriptures, there are also descriptions of druidic rites, especially in Cormac's Glossary (Sana Cormaic) from the 9th century from Cashel, and in some myths. In the ritual for prophesy, Tarbhfhíos, which means "bull knowledge," a white bull had to be slaughtered. The druid ate of the meat and the broth in which it was cooked, and then lay down on the fur of the animal to sleep, while four of his colleagues said incantations about him. In the case described, he saw in his sleep the shape and characteristics of the rightful king, and what he just did at the moment. A similar ritual was probably Imbas forosnai, "enlightenment of the bright knowledge", in which the flesh of a red pig, dog or cat should be eaten, after which one had to lay down for a three-days magic sleep, which also enabled one for divination. More difficult is the explanation of Teinm Laida, which could have meant "disclosure by the song". All three of these rituals were subsequently banned by Christianity, because they were associated with the invocation of pagan gods. A single ritual was not prohibited, Dichetal do chennaib, which means "reciting the ends", probably relating to the fingertips. It seems to have consisted of the recitation of certain wisdom teachings of the supernatural, the fingers could have served as a reminder, or a magic act in conjunction with the fingertips led to clairvoyance.

Now I want to share some more of the aforementioned tree alphabet of the druids. We have already seen that trees were of great importance for the religious beliefs of the Celts. They worshiped their gods in sacred groves and revered the mistletoe growing on oaks. The Celts in Gaul had tree-gods, such as the Deus Robur, the oak god of Angouleme, the Fagus, the beech-god from the Pyrenees, or the apple tree god, Abellio. Each tribe had its sacred tree under which the kings were crowned, or other rites took place. Such a sacred tree was called Bile, in the Gallic as well as in Irish, and in Ireland there were, corresponding to the five provinces, five such trees, namely the tree of Ross, a yew tree, the tree of Mugna, an oak tree, and the trees of Dathi , Uisneach and Tortu, all three ash trees. On the cutting of these sacred trees a death-sentence was afflicted, but at the time of Christianity this did not protect them anymore.

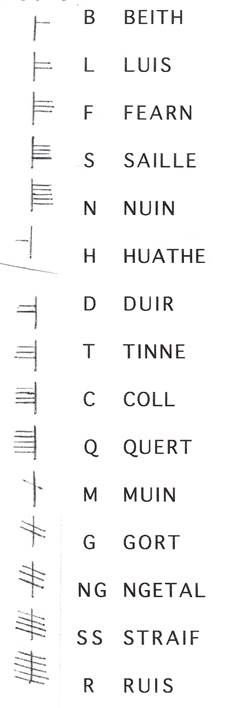

The Irish Celts possessed their own script, called Ogham-script. It consists of a system of straight lines, which have been attached along a vertical line from the center to the left, to the right, across it or in an inclined position and which in different numbers refer to the various letters. Also, they were very suitable to be placed on the edges of standing stones, with which often a particular event or person buried there was commemorated.

This script was mainly reserved for druids who engraved it on wooden panels, the so-called Coelbreni, that were used for oracle throwing. It could also be expressed with finger-signs, which enabled the scholars to a secret communication, impossible to understand for the uninitiated. This Ogham-letters were now associated in the form of an alphabet with certain trees, to which special significances and characteristics and sometimes gods were associated. There are several sources which, in slightly different form, deliver this alphabet. Most can be found in an Irish manuscript collection from the 14th century, the Book of Ballimote, including the legend of its creation. According to it, it was invented by Ogma, who belonged to the Tuatha Dé Danann, the people of the goddess Danu. He was regarded as the god of poetry and eloquence, and had the nickname "sun face", which could also indicate a sun-god.

This often secret knowledge of the alphabet was called crane -knowledge. The crane was an animal which was often associated with a goddess, moreover the silhouettes of the migration of cranes in the sky reminds one of the patterns of the Ogham alphabet. The sea-god Manannan Mac Lir had a bag of crane-skin, where he kept his magical paraphernalia.

Further descriptions of the tree-alphabet can be found in the text "The Scholar's Primer" from Scotland from the sixteenth century and in the book “Ogygia”, published in Ireland in 1793 by Roderick O'Flaherty, but probably a much older work. In it he affirms, that it is true druidic knowledge that has been passed down orally for many centuries. The different variants of the tree-alphabet were made known again in our time by Robert von Ranke-Graves in his book “The white goddess”. He suspects that the trees and the related letters also corresponded to the seasonal time-units, which might be possible, regarding the great worship the Celts had for the trees, and their importance for festivals and meetings. He tries a combination of trees and their letters with the Celtic lunar months, but starts it mistakenly at the winter solstice. He also mentions several systems of the alphabet, a shorter older one with seventeen characters, to which later more were added so that the final, complete version comprises over twenty-five letters, including five vowels and five diphthongs or double consonants. These were presented by Liz and Colin Murray, who begin with the Celtic New Year, the First of November, and have also issued fortune telling cards with images of trees with the Ogham letters. These are all interpretations of our time. But now the most complete version of this alphabet should be presented, so you can imagine, what it looks like.

The Ogham Tree Alphabeth

The Birch, Irish Beith, is the first tree and corresponds to the first consonant B. It stands for the beginning, a new start, fresh energy, and cleaning and is associated with the goddess Bríd or Brigid.

The next letter, L is represented by Luis, the Rowan. The mountain ash is a tree that is associated with fairies and witches, it is supposed to protect against magic and control its powers.

The alder, Fearn, is a tree, that loves water, it relates to dreams, divination and prophecy, and is connected with the Welsh god Bran.

The letter S stands for Saille, the willow. It corresponds to the water, the rhythms and tides, and therefore has a relationship with the female forces, the moon and intuition. It is also associated with the goddess Bríd.

The next letter, N, corresponds to Nuinn, the ash. This is a tree of the sun and connects the earth to the sky and the universe therefore it is also a tree of kings and magicians and is associated with the great Welsh magician Gwydion.

The second group of five consonants begins with H, the tree is Huathe or hawthorn. This is the tree of the fairies and elves, the Queen of May, of renewal and spring and must be treated with caution.

The next letter, D, belongs to Duir, the oak. It is known as a tree of strength and protection, firmness and power and is allocated to the good God of the Irish, the Dagda, as well as in ancient times to the similar gods Zeus and Jupiter.

Now follows the letter T and the tree Tinne, the Holly. This spiny, evergreen tree with red berries is representing the Green Knight, the tireless, fearless fighter who stands up for the just cause - and the characteristics of fighting power, steadfastness and the will to overcome.

The next letter, C, is connected to a shrub, Coll, the hazel. The hazelnuts are in Irish mythology a symbol of wisdom, omniscience, and poetic inspiration and correspond to the wise King Fionn and the bard.

To the tenth letter, Q, belongs Quert, the apple tree. This is the tree of the Celtic Otherworld, the land of eternal youth and beauty. Messengers from there often bring an apple branch with flowers and golden fruit at the same time as a sign with them. So the apple tree is connected to beauty and eternal life, and thus to the goddess of the land. Therefor the Otherworld is also named Avallon, which means land of apples.

The next letter, M is represented again not by a tree, but by the vine, Muin, which was probably taken early to the British Isles by the Romans. It stands for ecstasy, prophecy and enlightenment and is associated with the God Lugh, who was a magician, young and beautiful and a master in many arts..

The letter G is again not represented by a tree, but by Gort, the Ivy. It is a symbol of transformation, for the maze, for the search for the soul and its resurrection.

The next letter is a diphthong, Ng, and refers to the reeds, Ngetal, which is supposed to mean flexibility and determination. In another variant of the alphabet is here the letter P and the tree Peith, a kind of elder, but that is a later addition.

The next character is again a double letter, a sharp SS, which represents Straif, the blackthorn. It relates to the hardness and ruthlessness of winter and of fate with his hard thorns and acidic berries.

The letter R is connected to Ruis, the elder. It was regarded as a tree of change that has to do with the problem of death and life, but also with magic and witches, so it was rather feared.

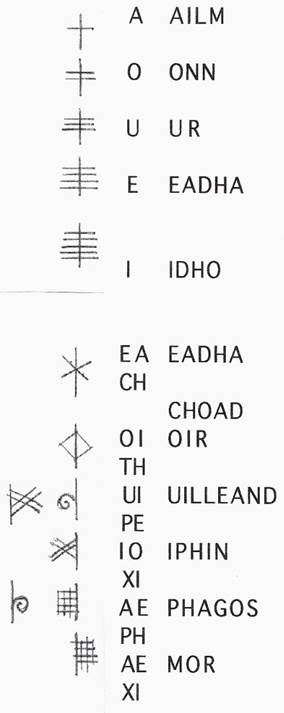

The vowels AOUEI form a separate group of five.

The letter A belongs to the tree Ailm, the fir or pine, which is also associated with the goddess Brigid and has the significance of vision, being upright, clear sight and knowledge.

To the letter O is belonging Onn, the gorse. It is believed to protect against witches and to bring fulfillment and wealth.

The letter U is connected to Ur, the heather. This plant has a lot to do with the underground areas, with fairies and elves, but also with the fertility of the earth.

The vowel E corresponds to Eadha, Aspen, and thus the ability to overcome difficulties, to strength and to perseverance. The wood was used for shields and to provide protection. But the trembling of the leaves of the tree is also associated with speech and the transmission of messages and the god Ogma.

I is the letter of the yew, Idho, that is often found in cemeteries. Yews can be incredibly old they symbolize death and rebirth, the resurrection from destruction, and the gateway to another world.

The last group of five letters was added later, and includes double consonants or double vowels in different versions.

The first of these, CH, or EA, is combined with Choad, the grove, or again with Eadha, Aspen, and refers to the communality.

OI or TH is represented by Oir, the spindle tree, meaning sudden realization and joy.

UI or PE refers to Uilleand, the wild honeysuckle, which should lead to the discovery of the mysteries of life and to decision.

IO or XI refers to Iphin, the gooseberry and the search for knowledge.

PH or AE are the beech, phagus, or the tradition and wisdom of the past. Sometimes Iphin is missing and IO, and the beech, Phagos for PH and now together with IO, stands second to last place, in which case the last position is occupied by AE and XI and paired with the sea, which stands for mystery.

In the collection of early Irish law texts, the so-called Brehon Laws dating from the fourteenth century, which are for the most part but much older, the trees are divided into classes, where the top class, the noble trees or prince trees, were held in high esteem, and it was forbidden under severe penalties, to cut them without a permit. Among these were the yew, the oak, the ash, the fir or pine tree, the apple tree, the holly and hazel. Later on, the alder, willow and the birch were added.

In the Welsh manuscript collections there can be seen as well that the trees were of great importance for the druids. Particularly interesting in this context is the poem “The battle of the Trees” or Kat Godeu from the 13th century, preserved in the Book of Taliesin. It is attributed to the famous bard, poet and probably druid Taliesin from the sixth century and tells, how an obviously into trees transformed army or rather trees equipped with human qualities wage battle.

An excerpt of which is for example:

"The alders, at the head of the troops, the vanguard,

Willows and mountain ash are late in the array ......

The hawthorn, armed with spines, stings in their hands,

The trembling aspen cuts off the heads

and is itself cleared in the turmoil.

The fern appears to be trampled, gorse ahead of all

was wounded in the ditch, furze is not hurt,

Although one finds it everywhere.

The heather is however victorious, because it knows how to protect all sides.

The deployment of the combatants also makes the people spellbound.

Under the treads of the oak tremble heaven and earth.

Struggling valiantly, its name still lives on for long. "

There are theories that here a battle of the gods, encrypted by the trees and the tree alphabet, is told. In the introduction to this poem, however, is another interesting item, namely a description of the transformations of Taliesin:

"I've already appeared in many aspects,

before I won a valid form for me.

I have been a gilded lance,

which I still remember today.

I have been a drop of rain in the wind,

I'm the farthest of stars,

I've been an ocean current, have been an eagle

and the fisherman's boat on the sea.

I have been the feast of a festival,

have been the drop in the cast,

I'm a sword in the hand of a warrior,

I have been a shield in battle

I have been the string of the harp

and that nine years.

I’m the water, the foam,

I’ve been a sponge in the fire.

I’m indeed a mysterious wood ".

A similar idea of transforming power is found in the poem by the Irish druid Amergin, which was cited in the first chapter.

In Welsh mythology there also occurs frequently the transformation into animals.

In the collection of myths, the Mabinogi, for example, the old Magician King Math ap Mathonwy, who clearly shows druidic abilities, changes his unruly nephews, the magician apprentice Gwydion and his brother Gilvaethwy, as a punishment for one year into two deer, for one year into two wild boars and for a third year into two wolves. The soul of the murdered Lleu is transformed into an eagle, his wife Blodeuwedd, who ordered the murder, is transformed by Gwydion into an owl. Even Merlin from the Arthurian myths, who emerged from the Welsh Bard Myrrdhin, and who is described as a druid and wise adviser of King Arthur, is credited with an enormous ability of shape-shifting. He appears once as an old ragged old man, then as a strong younger man and hides in trees and bushes. This power of transformation, which is attributed to the druids in the ancient Irish and Welsh texts, has a strong shamanic component and shows their great connection to animals, plants and nature in general. The ecstasy of prophecy and prediction of the future is often described similar to the shaman. The ability of poetic writing and poetic inspiration was also perceived as divine power, of which one was possessed, so to speak, and named in Wales with the word Awen. The bards and druids were also known under the name Awenyddion. Here, too, the class of the bards, the Cynfeirdd, existed until the fifteenth century and wrote down many of the ancient texts. Included among them were the Gogynfeirdd (court poets), Penceirdd (chief poets), Bardd teulu (army poets), Cleryr (satirists), Prydydd (price bards) , Gwayrudd Beirdd (fighting bards), Cyfarwydd (story-teller), and Oferfardd (amateur bards). Famous bards were Cynddelw, Owain Cyfeiliog and Gruffudd ap Maredudd. From the fifteenth century on the poets were called Cywyddwyr.

In Welsh literature one can also recognize the concept of a worldview of the Druids, which consists of several worlds, which are permeating each other. The innermost or deepest circle or sphere is Annwn or the Otherworld, it is not horrible, but the source of the defining, shaping and life-giving elemental forces and represents a kind of collective sub-consciousness from which one can draw clairvoyantly. It is the home of fairies and gods, such as the kings Arawn or Gwyn ap Nudd or Morgane and the nine women who guard the cauldron of inspiration and rebirth. The second area, called Abred, is our real, physical world in which the forces of the different worlds achieve their manifestation. Abred is enveloped or permeated by Gwynwydd, the next world of white, bright light, from which the divine powers and the sublime ideas and ideals emanate into this world. It has a certain resemblance to paradise from which it but differs a lot, most of all by the absence of the antithesis of a punitive hell. There are several areas, such as the beautiful land of eternal youth, called in Irish Tir na n'Óg, to which you can obviously go after death if one has fulfilled certain tasks on earth in order to continue to live there as a semi-divine being. One can also be born again from there on earth to learn certain things and gain insights. There is in this place neither sickness, old age nor death, everything is beautiful and noble, but similar to our world, there are feelings, problems and struggles, you have to continue learning here. This range overlaps and often cannot be clearly separated from the actual fairy world and the world of wonders, which is the home of the gods like Bríd, Danu or Lugh, which is even more remote to earth. Then there seems to be a world of light, where the great cosmic entities and powers of creation have their origin. The whole world is enveloped in the concept of Ceugant, the unmanifested, formless Divine that is so sublime that it is impossible for people to understand it.

From all this traditional knowledge about the druids and their views a renewal movement of druidism was initiated in the seventeenth and eighteenth century in Wales. Much of it is based on real traditions, but much is also a contribution of that time, in which people were looking for their roots and wanted according to the Renaissance of antiquity in many European countries to initiate a Celtic Renaissance.

The main character of this movement was in the 18th century the Welsh Edward Williams, who called himself Iolo Morgannwg and wrote some books in this sense. The still active successive movements of today are several orders of druids, some of which maintain the esoteric and philosophical tradition, others, in turn, are more active in the field of the protection of the environment or are dedicated to cultural issues, such as the groups that organize the Welsh Eisteddfod, a large annual cultural festival in Welsh language with presentations of music contests, folk dance groups, drama, poetry and recitations, but also the druidic ceremony of the Gorsedd, with clothes and attire modeled after archaeological findings. How far this is a genuine survival of a tradition or a romantic nostalgic matter, is difficult to decide.

Similar groups have emerged in Cornwall and Brittany. In England there are some druid orders, such as "The Ancient Druid Order," which usually celebrates the Celtic festivals on ancient sites, and OBOD, "The Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids", which uses a training and teaching program, based on the ancient traditions. Both go back to a foundation in the year 1717. "The Ancient Order of Druids" in turn, has largely social and welfare objectives.

Many ideas of druidism are certainly very useful and can nowadays provide to us possible solutions to our problems, such as the respect and consideration for nature and the world and the consciousness of being a part of the whole universe, to behave accordingly and to live in unity with it, and the appreciation of creativity, arts, poetry and philosophy.

Also with regard to the legal system there are quite sensible approaches, such as the jurisdiction of compensations, which does not rely on the punishment of the transgressor, but on the reason, that he and his family had to make good the damage and harm done by him, be it a material or immaterial damage and the relative extent of equality of women, both in treasury, in the social position and in profession, and in the free choice of marriage and in equality to the spouse.

So it makes sense to deal today with the views and concepts of life of the Druids, to rescue them from the past and present them to a wider audience.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Selected sources:

Ian Adamson: The Cruithin – A History oft the Ulster Land and People, Belfast 1986

Bo Almquist – Séamas Ó Catháin – Pádraig Ó Héalaí: Fianníocht – Essays oft the Fenian Tradition of Ireland and Scotland, Dublin 1986/87

Geoffrey Ashe: Kelten, Druiden und König Arthur, Freiburg i. Breisgau 1992

Geoffrey Ashe: King Arthurs Avalon, Isle of Man 1979

Geoffrey Ashe: The Quest for Arthur’s Britain, St. Albans 1979

Geoffrey Ashe: König Arthur, Düsseldorf – Wien 1986

Osborn Bergin: Irish Bardic Poetry, Dublin 1984

Peter Berresford Ellis: The Celtic Empire, London 1990

Peter Berresford Ellis: Celtic Women, London 1995

Helmut Birkhan: Keltische Mythen und Märchen, Wien – München 1987

Helmut Birkhan: Keltische Erzählungen vom Kaiser Arthur, Band 1 und 2, in: Erzählungen des Mittelalters, Kettwig 1989

Helmut Birkhan: Kelten: Versuch einer Gesamtdarstellung ihrer Kultur Verlag der Österr.Akademie der Wissenschaften Wien 1999

Helmut Birkhan: Nachantike Keltenrezeption, Wien 2009

Aodh de Blácam: Gaelic Literature Surveyed, Dublin 1973

Sylvia und Paul Botheroyd: Lexikon der Keltischen Mythologie, München 1992

Rachel Bromwich: Armes Prydein – The Prophecy of Britain from the Book of Taliesin, Dublin 1992

Rachel Bromwich ed.: The Beginnings of Welsh Poetry, Cardiff 1980

Rachel Bromwich: Trioedd Ynys Prydein – The Welsh Triads, Cardiff 1978

Jean Louis Bruneaux: Druiden- Die Weisheit der Kelten,

Paris 2006

Jean Louis Bruneaux: The Celtic Gauls – Gods, Rites and

Sanctuaries, London 1988

James Cable: The Death of King Arthur – La Mort le Roi Arthu, Harmondsworth 1985

Moyra Caldecott: Women in Celtic Myth, London 1988

Proinsias Mac Cana: Celtic Mythology, Rushden 1984

Ingeborg Clarus: Keltische Mythen, Olten 1991

James Carney: Medieval Irish Lyrics, with: The Irish Bardic Poet, Dublin 1985

James Carney: Studies in Irish Literature and History, Dublin 1979

Philip Carr-Gomm: The Druid Renaissance, London 1996

Philip Carr-Gomm: The Druid Tradition, Longmead Shaftesbury 1991

Tomás Ó Cathasaigh: The Heroic Biography of Cormac Mac Airt, Dublin 1977

Richard Cavendish: King Arthur and the Grail, London 1980

Nora Chadwick: The Celts, Harmondsworth 1986

Daniel Corkery: The Hidden Ireland, Gill and Macmillan, Dublin1986

Dáibhí ó Cróinin ed.: Anew History of Ireland – Prehistoric and early Ireland

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|