- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Model. Part 1.

Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Model. Part 1.

Eli Heckscher was born on November 24, 1879, in Stockholm. He completed his secondary education there in 1897. Heckscher studied at the university in Uppsala under David Davidson and was subsequently a docent under Cassel at Stockholm and Gothenburg, completing his Ph.D. in Uppsala, in 1907.

Eli Heckscher was born on November 24, 1879, in Stockholm. He completed his secondary education there in 1897. Heckscher studied at the university in Uppsala under David Davidson and was subsequently a docent under Cassel at Stockholm and Gothenburg, completing his Ph.D. in Uppsala, in 1907.

He was professor of Political economy and Statistics at the Stockholm School of Economics from 1909 until 1929. When he exchanged that chair for a research professorship in economic history, he became founder and director of the Stockholm Institute for Economic History, finally retiring as emeritus professor (заслуженный профессор в отставке) in 1945. In fact, he established economic history as an independent academic discipline in Sweden.

According to a bibliography published in 1950, Heckscher had as of the previous year published 1,148 books and articles, among which may be mentioned his study of Mercantilism, translated into several languages, and a monumental economic history of Sweden in several volumes. Although Heckscher is now chiefly remembered as an economic historian, he also made several contributions to economic theory, including the concept of commodity points, which limits the fluctuation of inconvertible paper currencies (Heckscher, 1919). Heckscher is best known for a model explaining patterns in international trade that he developed with Bertil Ohlin.

As Heckscher died on November 26, 1952, in Stockholm, he could not be given a posthumous (посмертный) Nobel Prize for his work on the Heckscher-Ohlin Theory. Instead, Bertil Ohlin was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1977 (together with British economist James E. Meade) for his contribution to the theory of international trade, based on the work he did with Heckscher.

Bertil Ohlin was born on April 23, 1899 into an upper-middle class family in a village in the south of Sweden. He received his B.A. (Bachelor of Arts)[1] from Lund University 1917. Having seen in a newspaper a review of a book about the economic aspects of the world war, The Continental System: An Economic Interpretation in 1918, a study of Napoleon’s blockade of England and its relation to the mercantilist system, written by Eli Heckscher who was professor at the Stockholm Business School, young Bertil Ohlin suggested to his parents, that he should take up studies there.

Bertil Ohlin was born on April 23, 1899 into an upper-middle class family in a village in the south of Sweden. He received his B.A. (Bachelor of Arts)[1] from Lund University 1917. Having seen in a newspaper a review of a book about the economic aspects of the world war, The Continental System: An Economic Interpretation in 1918, a study of Napoleon’s blockade of England and its relation to the mercantilist system, written by Eli Heckscher who was professor at the Stockholm Business School, young Bertil Ohlin suggested to his parents, that he should take up studies there.

This he did. Later on, Ohlin moved to the philosophical faculty of Stockholm University where his teachers were Gustav Cassel and Gösta Bagge. During his studies in Sweden he spent few months in 1922 in Cambridge, England and thereafter in Harvard University. Ohlin finished his studies and received his doctorate from Stockholm University in 1924.

In 1925 he became a professor of economics at the University of Copenhagen. Throughout the next five years he reworked his Ph.D. thesis into a ground-breaking publication (Ohlin, 1933).

In 1931 Bertil Ohlin succeeded Eli Heckscher, his teacher, as professor of economics, at the Stockholm School of Economics. In 1933, Ohlin published a work that made him world renowned, Interregional and International Trade. The book was characterized by an attempt to pay more attention to how factor supply, location, taxation, social policy, and risk affect international division of labor. Ohlin built an economic theory of international trade from earlier work by Heckscher and his own doctoral thesis. It is now known as the Heckscher-Ohlin model, one of the standard models economists use to debate trade theory.

Ohlin was jointly awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 1977 together with the British economist James Meade "for their pathbreaking contribution to the theory of international trade and international capital movements."

Later, Ohlin and other members of the "Stockholm school" extended Knut Wicksell's economic analysis to produce a theory of the macroeconomy anticipating Keynesianism.

Bertil Ohlin died on August 3, 1979, in Valadalen, Sweden.

The basis for the Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Model is that countries differ in their endowment of resources. Industrial countries are endowed with relatively large amounts of capital and skilled labor, whereas developing nations are primarily characterized as having large amounts of unskilled labor. These resource endowment differences lead to different countries being most efficient in producing certain types of goods. That is to say, countries would specialize in the production of those goods for which they have a comparative advantage.

In order to develop the Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Model, we must first make simplifying assumptions. This model is a 2 good by 2 input by 2 country model. So let's have two different goods (clothing and planes), two inputs ( labor {L} and capital {K}), and lastly two countries, the US and Mexico.

We need to initially establish a vocabulary. The two goods are different from each other because they use relatively different amounts of labor and capital used in their production. We define clothing as labor intensive meaning that its production uses relatively more labor than capital in its production as compared to the production of planes. On the other hand, planes are termed capital intensive because relatively more capital is used in their production than in clothing.

Clothing - Labor Intensive

Planes - Capital Intensive

The two countries, the US and Mexico, differ from each other in their relative endowments of labor and capital. We assume that the two countries are identical in every other way, in particular

1) that they have access to the same technologies and

2) that consumers have identical preferences.

These assumptions allow us to base our analysis solely on the difference in resource endowments.

We define the US as being capital abundant. This means that the US has relatively more capital than labor compared to Mexico. Mexico would then be labor abundant, since it has relatively more labor than capital compared to the US.

US - Capital Abundant

Mexico - Labor Abundant

Note that goods are defined in terms of intensities, while countries in terms of abundances.

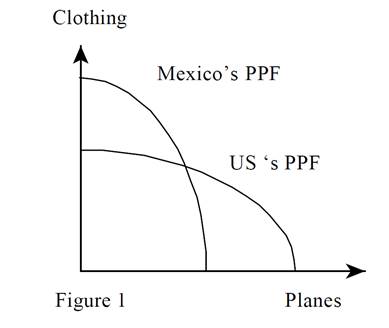

The difference in the countries' resource endowments gives rise to differently shaped PPFs. The US being capital abundant can produce relatively more planes than clothing. The reverse would be true for Mexico. Figure 1 shows the US and Mexican PPFs. The US's PPF stretches over the horizontal axis, whereas Mexico's PPF stretches along the vertical axis.

Since both countries have identical preferences, they would have the same family of indifference curves. Therefore, we can portray their preferences with the same set of indifference curves.

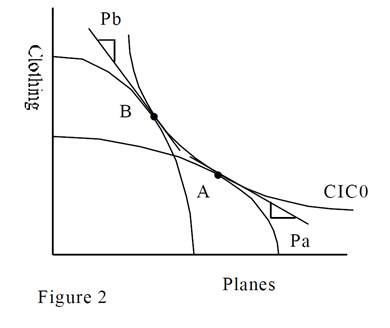

We start the analysis where both the US and Mexico are simultaneously in autarkic general equilibria. The US, closed economy, could do no better than point A in Figure 2. Mexico's autarkic equilibrium is achieved at point B.

We have scaled the graph so that the US and Mexico achieve the same social utility level. This does not necessarily have to be the case, but it makes the graphs simpler to understand.

These general equilibria are achieved by the autarkic prices Pa and Pb, for the US and Mexico, respectively.

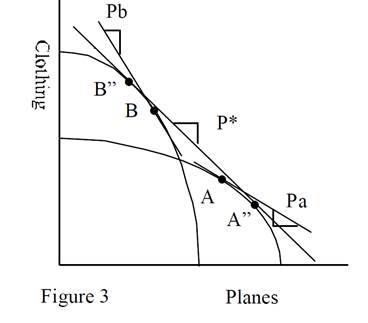

Now, the two countries open up to trade. In order for trade to occur, we will need to fulfill an important condition. The terms of trade (the prices at which the US and Mexico will exchange goods) will necessarily be in between the two countries' autarkic prices. Since in autarky Pb is steeper than Pa, Mexicans have a higher relative price for planes in terms of clothing than does the US. Therefore, in order to exchange airplanes for clothing, the relative price must be higher than the US's autarkic price, but lower than Mexico's relative price. Explicitly,

Pb > P* > Pa,

where P* is the terms of trade (price planes / price clothing) between the two countries.

We also allow efficient production by allowing producers in both countries to respond to the new set of prices, P*. In order to maximize profits, production will shift along each county's PPF to where P* equals its MRT.

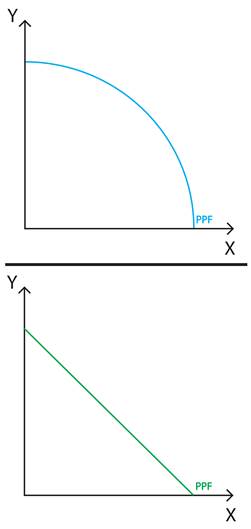

The marginal rate of transformation (MRT) can be defined as how many units of good x have to stop being produced in order to produce an extra unit of good y, while keeping constant the use of production factors and the technology being used. It involves the relation between the production of different outputs, while maintaining constant the same level of production factors. It can be determined using the following formula:

The MRT is related to the production possibilities frontier (PPF). The slope of the curves shows how a reallocation of the production can end with a different bundle of production, using the same quantity of inputs. Two of the most commonly used PPFs are depicted in the adjacent figure.

In the first graph, the MRT will change along the curve.

The second graph, which portrays the case of perfect substitutes output, that is the slope has an angle of 45º with each axis and therefore we have MRT = 1. When considering different substitutes goods, the slope will be different and the MRT can be defined as a fraction, such as 1/2 ,1/3, and so on. For perfect substitutes, the MRT will remain constant.

Figure 3 illustrates these conditions. The first condition is met. Pb is steeper than P* which in turn is steeper than Pa. Thus Pb > P* > Pa. Profit maximization is also shown because P* is tangent to both PPFs at A" & B". These tendencies suggest that producers in both countries are maximizing their profits.

Note that production shifts in both countries. The US moves from point A to A", or increases plane production and decreases clothing output. The opposite is true for Mexico as it moves production from B to B". This shift in production represents each country specializing in the production of a particular good, planes in the US and clothing in Mexico. This is an important result that we will address shortly.

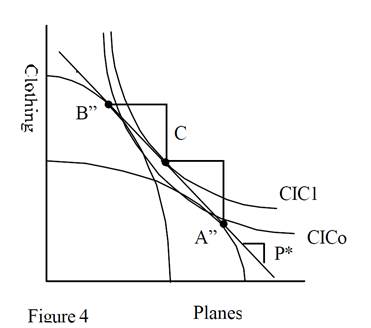

Now that production occurs at A" and B", the next topic to address is consumption. Unlike autarky, countries A and B are now able to trade with each other and by definition of the terms of trade exchange goods along the P* price line. Utility maximization occurs at the commodity bundle whose indifference curve is tangent to P*. This occurs at point C in Figure 4.

With consumption at point C (note: for both countries) we can show each country's imports and exports trade patterns by the use of a trade triangle along P* from the point of production to the point of consumption. When production exceeds consumption, the excess is exported. If consumption exceeds production, it must be the case that the good is being imported. For the US, the height of the triangle represents clothing imports and its length represents plane exports. Note that for Mexico the opposite is true. The height of its trade triangle represents its exports while the length represents its imports.

The patterns of trade show that the US specializes in and exports planes and Mexico specializes in and exports clothing. This unsurprising but important result is called the Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem. Formally, this theorem states that a country specializes in the production and export of that good which uses its abundant input intensively.

Also note that both countries are better off. The social indifference curve passing through point C is at a higher utility level than in autarky.

[1] A Bachelor of Arts is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|