- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION

THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION

Federal State Education Institution of higher Professional Education

“Penza State University”

"History Department"

Course Work

William Osler (1849–1919) — the "father of modern

medicine"

Student: mohammad ahmad haidar

Group: 19ll10 (a)

Accepted: Gavrilova Tatiana

Penza 2020

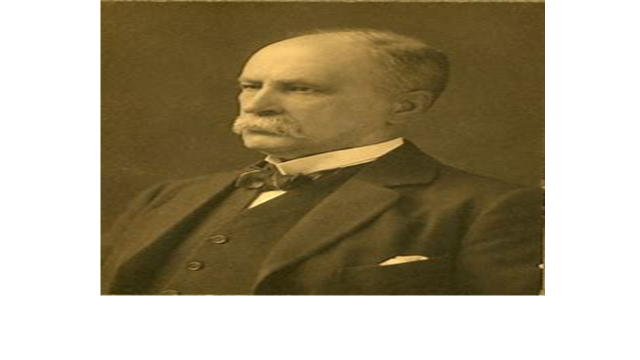

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, FRS FRCP (/ˈɒzlər/; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the four founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of physicians, and he was the first to bring medical students out of the lecture hall for bedside clinical training.[1] He has frequently been described as the Father of Modern Medicine and one of the "greatest diagnosticians ever to wield a stethoscope".[2][3] Osler was a person of many interests, who in addition to being a physician, was a bibliophile, historian, author, and renowned practical joker. One of his achievements was the founding of the History of Medicine Society (previously section) of the Royal Society of Medicine, London

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, FRS FRCP (/ˈɒzlər/; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the four founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of physicians, and he was the first to bring medical students out of the lecture hall for bedside clinical training.[1] He has frequently been described as the Father of Modern Medicine and one of the "greatest diagnosticians ever to wield a stethoscope".[2][3] Osler was a person of many interests, who in addition to being a physician, was a bibliophile, historian, author, and renowned practical joker. One of his achievements was the founding of the History of Medicine Society (previously section) of the Royal Society of Medicine, London

Family[edit]

William's great-grandfather, Edward Osler, was variously described as either a merchant seaman or a pirate.[5] One of William's uncles (Edward Osler (1798–1863)), a medical officer in the Royal Navy, wrote the Life of Lord Exmouth and the poem The Voyage. (Osler, Edward, 1798–1863. The Voyage : a poem, written at sea, and in the West Indies, and illustrated by papers on natural history. London : Longman, 1830). William Osler's father, Featherstone Lake Osler (1805–1895), the son of a shipowner at Falmouth, Cornwall, was a former Lieutenant in the Royal Navy who served on HMS Victory. In 1831 Featherstone Osler was invited to serve on HMS Beagle as the science officer on Charles Darwin's historic voyage to the Galápagos Islands, but he turned it down because his father was dying. In 1833, Featherstone Osler announced he wanted to become a minister of the Church of England.[6]

As a teenager, Featherstone Osler was aboard HMS Sappho when it was nearly destroyed by Atlantic storms and left adrift for weeks. Serving in the Navy, he was shipwrecked off Barbados. In 1837 Featherstone Osler officially retired from the Navy and emigrated to Canada, becoming a "saddle-bag minister" in rural Upper Canada. When Featherstone Osler and his bride, Ellen Free Picton, arrived in Canada, they were nearly shipwrecked again on Egg Island in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The Oslers had several children, including William, Britton Bath Osler,and Sir Edmund Boyd Osler.

Early life[edit]

William Osler was born in Bond Head, Canada West (now Ontario), on July 12, 1849, and raised after 1857 in Dundas, Ontario. (He was called William after William of Orange, who won the Battle of the Boyne on July 12, 1690.) His mother, who was very religious, prayed that Osler would become a priest.[7] Osler was educated at Trinity College School (then located in Weston, Ontario).

In 1867, Osler announced he would follow his father's footsteps into the ministry and entered Trinity College, Toronto (now part of the University of Toronto), in the autumn. At the time, he was becoming increasingly interested in medical science, under the influence of James Bovell, and Rev. William Arthur Johnson, encouraging him to switch his career.[8][9][10] In 1868, Osler enrolled in the Toronto School of Medicine,[11] a privately owned institution, not part of the Medical Faculty of the University of Toronto. Osler lived with James Bovell for a time, and through Johnson, he was introduced to the writings of Sir Thomas Browne; his Religio Medici caused a deep impression on him.[12] Osler left the Toronto School of Medicine after being accepted to the MDCM program at McGill University Faculty of Medicine in Montreal and he received his medical degree (MDCM) in 1872.

Career[edit]

Following post-graduate training under Rudolf Virchow in Europe, Osler returned to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine as a professor in 1874. Here he created the first formal journal club. During this time, he also showed interest in comparative pathology and is considered the first to teach veterinary pathology in North America as part of a broad understanding of disease pathogenesis. In 1884, he was appointed Chair of Clinical Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and in 1885, was one of the seven founding members of the Association of American Physicians, a society dedicated to "the advancement of scientific and practical medicine." When he left Philadelphia in 1889, his farewell address, "Aequanimitas",[13] was on the imperturbability (calm amid storm) and equanimity (moderated emotion, tolerance) necessary for physicians.[14]

n 1889, he accepted the position as the first Physician-in-Chief of the new Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Shortly afterwards, in 1893, Osler was instrumental in the creation of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and became one of the school's first professors of medicine. Osler quickly increased his reputation as a clinician, humanitarian, and teacher. He presided over a rapidly expanding domain. In the hospital's first year of operation, when it had 220 beds, 788 patients were seen for a total of over 15,000 days of treatment. Sixteen years later, when Osler left for Oxford, over 4,200 patients were seen for a total of nearly 110,000 days of treatment.[15]

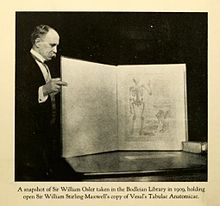

In 1905, he was appointed to the Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, which he held until his death. He was also a Student (fellow) of Christ Church, Oxford.

In the UK, he initiated the founding in 1907 of the Association of Physicians[16] and was founding Senior Editor of its publication the Quarterly Journal of Medicine until his death.[17]

In 1911, he initiated the Postgraduate Medical Association, of which he was the first President.[18] In the same year, Osler was named a baronet in the Coronation Honours List for his contributions to the field of medicine.[19]

In January 1919 he was appointed President of the Fellowship of Medicine [20] and was also in October 1919 appointed founding President of the merged Fellowship of Medicine and Postgraduate Medical Association,[21] now the Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine.

The largest collection of Osler's letters and papers is at the Osler Library of McGill University in Montreal and a collection of his papers is also held at the United States National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[22][23]

Personal life and family

An inveterate prankster, he wrote several humorous pieces under the pseudonym "Egerton Yorrick Davis", even fooling the editors of the Philadelphia Medical News into publishing a report on the extremely rare phenomenon of penis captivus, on December 13, 1884.[35] The letter was apparently a response to a report on the phenomenon of vaginismus reported three weeks previously in the Philadelphia Medical News by Osler's colleague Theophilus Parvin.[36] Davis, a prolific writer of letters to medical societies, purported to be a retired U.S. Army surgeon living in Caughnawaga, Quebec (now Kahnawake), author of a controversial paper on the obstetrical habits of Native American tribes that was suppressed and unpublished. Osler would enhance Davis's myth by signing Davis's name to hotel registers and medical conference attendance lists; Davis was eventually reported drowned in the Lachine Rapids in 1884.[36]

Throughout his life, Osler was a great admirer of the 17th century physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne.

He died at the age of 70, on December 29, 1919, in Oxford, during the Spanish influenza epidemic, most likely of complications from undiagnosed bronchiectasis.[37] His wife, Grace, lived another nine years but succumbed to a series of strokes. Sir William and Lady Osler's ashes now rest in a niche in the Osler Library at McGill University. They had two sons, one of whom died shortly after birth. The other, Edward Revere Osler, was mortally wounded in combat in World War I at the age of 21, during the 3rd battle of Ypres (also known as the battle of Passchendaele). At the time of his death in August 1917, he was a second lieutenant in the (British) Royal Field Artillery;[38] Lt. Osler's grave is in the Dozinghem Military Cemetery in West Flanders, Belgium.[39] According to one biographer, Osler was emotionally crushed by the loss; he was particularly anguished by the fact that his influence had been used to procure a military commission for his son, who had mediocre eyesight.[40] Lady Osler (Grace Revere) was born in Boston in 1854; her paternal great-grandfather was Paul Revere.[41] In 1876, she married Samuel W. Gross, chairman of surgery at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. Gross died in 1889 and in 1892 she married William Osler who was then professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

Osler was a founding donor of the American Anthropometric Society, a group of academics who pledged to donate their brains for scientific study. Osler's brain was taken to the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia to join the Wistar Brain Collection. In April 1987 it was taken to the Mütter Museum, on 22nd Street near Chestnut in Philadelphia where it was displayed during the annual meeting of the American Osler Society.[42][43]

In 1925, a biography of William Osler was written by Harvey Cushing,[44] who received the 1926 Pulitzer Prize for the work. A later biography by Michael Bliss was published in 1999.[40] In 1994 Osler was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame.[45]

Eponyms[edit]

Osler lent his name to a number of diseases, signs and symptoms, as well as to a number of buildings that have been named for him.[46][47]

Conditions[edit]

Osler's sign is an artificially high systolic blood pressure reading due to the calcification of atherosclerotic arteries

Osler's nodes are raised tender nodules on the pulps of fingertips or toes, suggestive of subacute bacterial endocarditis. Osler described them as "ephemeral spots of a painful nodular erythema, chiefly in the skin of the hands and feet." Osler nodes are usually painful, as opposed to Janeway lesions which are due to emboli and are painless.

Osler–Weber–Rendu disease (also known as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia) is a syndrome of multiple vascular malformations on the skin, in the nasal and oral mucosa, in the lungs and elsewhere.

Osler–Vaquez disease (also known as Polycythemia vera)

Osler–Libman–Sacks syndrome is an atypical, verrucous, nonbacterial, valvular and mural endocarditis. Final stage of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Osler's manoeuvre: in pseudohypertension, the blood pressure as measured by the sphygmomanometer is artificially high because of arterial wall calcification. Osler's manoeuvre takes a patient who has a palpable, although pulseless, radial artery while the blood pressure cuff is inflated above systolic pressure; thus they are considered to have "Osler's sign."[citation needed]

Osler's rule: States that a neurological defect has to be related to a specific lesion, in contrast to Hickam's dictum, which states that the neurological defect can be due to several lesions.[citation needed]

Osler's syndrome is a syndrome of recurrent episodes of colic pain, with typical radiation to back, cold shiverings and fever; due to the presence in Vater's diverticulum of a free-moving gallstone which is larger than the orifice.[citation needed]

Osler's triad (also known as Austrian Syndrome): association of pneumonia, endocarditis, and meningitis.[48][49]

Sphryanura osleri is a trematode worm found in the gills of a newt.[citation needed]

Oslerus osleri is a metastrongyloid nematode lungworm parasite of wild and domestic canids. Osler discovered the parasite while teaching comparative pathology at McGill.[citation needed]

Buildings

Osler Building at The Johns Hopkins Hospital currently The Johns Hopkins Hospital Human Resources. Until 2012 the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU) was located on the 7th floor.

Sir William Osler Elementary School – Elementary School in Vancouver, British Columbia

Ecole Sir William Osler School –Elementary School Winnipeg, Manitoba

Sir William Osler Elementary School – HWDSB Elementary School in Dundas, Ontario.

Sir William Osler High School,[50] Toronto, Ontario

Sir William Osler Public School[51] Simcoe County District School Board Elementary School in Bradford West Gwillimbury, Ontario and 3 kilometres away from his birthplace, Bond Head, Ontario.

Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal. Osler left his 8000 volume collection of books on the history of medicine to his alma mater. The library now holds over 100,000 volumes and is Canada's de facto 'national library of the history of medicine'.

Promenade Sir-William-Osler (Formerly the upper section of rue Drummond.) adjacent to the campus of McGill University in Montreal, Quebec and leading to the McIntyre Medical Sciences Building, which houses the Osler Library of the History of Medicine.

William Osler Health System 1998 near Brampton, Ontario

Osler House is the student mess for clinical medical students of Oxford University and is found at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford.

Osler House is also the name of the old Observer's House, next to the Radcliffe Observatory in Green Templeton College, Oxford, a Grade I listed building.[52]

Osler House is one of the two undergraduate hostels of the JIPMER medical school in Puducherry, India.

Osler Textbook Room 1999 at Johns Hopkins Hospital[53] in the room in the Billings Building where Osler wrote "Principles and Practice of Medicine". It houses a collection of Osler memorabilia.

Osler Center for Clinical Excellence 2002[54] devoted to teaching "the basic elements of a sound doctor patient relationship".

Osler Hall is Dining Hall at Trinity College School, Port Hope, Ontario.

Osler Hall is Main Hall of "Med Chi" or Medical and Chirurgical Faculty, the Maryland State Medical Society,[55] located on Cathedral Street in Baltimore. The Med Chi House of Delegates meets and deliberates in Osler Hall wherein hang numerous portraits of famous Maryland physicians including a large portrait of Osler.

Osler House (a medical residence) in Townsville, Queensland, Australia is believed to be named after him [56]

Osler was known to say, “He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all.”

Awards[edit]

American Association for the History of medicine, William Osler Medal.[57][58]

Osler Library, McGill University

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|