- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Richard lower

Federal State Budget Educational Establishment

Of Higher education “Penza state university”

Penza state university

Medical institute

Department of History

Course Paper

in History of Medicine

Richard lower

Student: Youssef Nasser

Group: 19LL10(a)

Check: Tatyana Gavrilova

Penza: 2019/2020

Richard lower

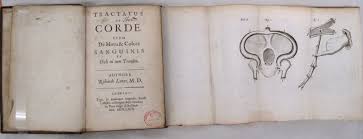

Lower was born in St Tudy, Cornwall and studied at Westminster School where he met John Locke, and Christ Church, Oxford where he met Thomas Willis. He followed Willis to London, where he carried out research, some in partnership with Robert Hooke. His major work, Tractatus de Corde (1669) was concerned with the workings of the heart and lungs, and he experimented with blood transfusion.

Lower formed part of an informal research team, performing laboratory experiments at the University of Oxford during the Interregnum. He was a pioneer of experimental physiology. He earned an M. D. degree in 1665. Lower was a medical student under Willis (Professor of Natural Philosophy from 1660 to 1675) and then collaborated with him to investigate the nervous system. He began his own research on the heart. He traced the circulation of blood as it passes through the lungs and learned that it changes when exposed to air. He was the first to observe the difference in arterial and venous blood.

Lower showed it was possible for blood to be transfused from animal to animal and from animal to man intravenously, a xenotransfusion. In November 1667, he worked with Edmund King, another student of Willis, to transfuse sheep's blood into a man who was mentally ill. Lower was interested in advancing science but also believed the man could be helped, either by the infusion of fresh blood or by the removal of old blood. It was difficult to find people who would agree to be transfused, but an eccentric scholar, Arthur Coga, consented and the procedure was carried out by Lower and King before the Royal Society on 23 November 1667. Transfusion gathered some popularity in France and Italy, but medical and theological debates arose, resulting in transfusion being prohibited in France.

Lower studied the arterial circle at the base of the brain, named the circle of Willis after his teacher. He wanted to see if blood would continue to flow through the head if three of the four arteries supplying blood to the head were tied.

Lower also investigated to see how cerebrospinal fluid was formed and how it circulated. These experiments led to a study of hydrocephalus, a disease in which fluid collects in the cavities of the brain. In Lower's time, it was thought that catarrh, an inflammation of the mucous membranes, might be caused by seepage of fluid from the brain to the nose. De Catarrhis, Lower's book, is of historical significance because it was the first scholarly attempt by an English physician to take a classical doctrine (the theory that nasal secretions are an overspill from the brain) and to disprove it by scientific experiment.

Lower wrote Diatribae T. Willisii de Febribus Vindicatio, an eight-volume defence of Dr. Willis and his doctrine of fevers. In keeping with his interest in the circulatory system, Lower went on to write Tractatus de Corde, which described the muscular fibres of the heart, a method of ligaturing veins to produce dropsy, blood coagulation in the heart, the motion of digestive fluids, and other physiologic topics. Lower presented his Tractatus de Corde to the Royal Society in 1669.

Willis died in 1675 and Lower became busy with the demands of his medical practice. He took care of Charles II during his final illness in 1685. When James II took the throne, Lower did not continue as court physician because of his anti-Catholic and Whiggish sentiments. However, he was consulted during pregnancy by the woman who would later become Queen Anne. [3]

Lower died in London from a fever.

References

1. 1691. " The People's Chronology. Ed. Jason M. Everett. Thomson Gale, 2006. eNotes. com. 2006. 26 May 2007

2. Tubbs, R Shane; Loukas Marios; Shoja Mohammadali M; Ardalan Mohammad R; Oakes W Jerry (August 2008). " Richard Lower (1631–1691) and his early contributions to cardiology"

3. Anne Somerset, Queen Anne: the Politics of Passion, London, 2012, p. 86

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|