- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

PRUNING PALS

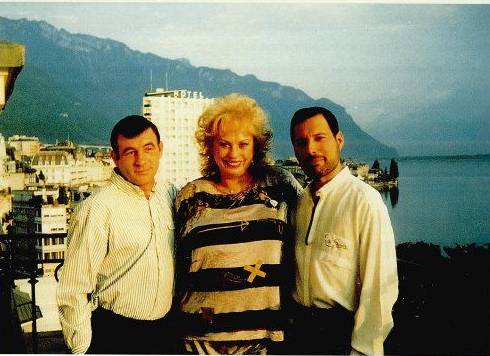

On a flying visit to Montreux in 1990, Freddie and I stayed at the Montreux Palace Hotel with Joe and Barbara Valentin. It was on that trip that he wrote his song ‘Delilah’, dedicated to his favourite cat.

The shops were still open when the four of us were walking back from the studio at the end of the day. Freddie was now on the look-out for beautiful linen, mostly tablecloths. Displayed in one shop window was something so camp we all burst out laughing. It was a Minnie and Mickey Mouse night outfit with shirt, shorts and a Wee Willie Winkie bobble hat. Barbara slipped back to buy it as a present for Freddie, which she gave him back at the hotel.

Later Joe and I turned in, but Freddie and Barbara didn’t. They were in the mood to talk all night.

I got up at seven in the morning and went into the sitting room where Freddie and Barbara were still wide awake and going strong. He looked a sight. He was wearing his new Minnie and Mickey outfit, including the Wee Willie Winkie hat.

‘Oh, it’s that time already, ’ he said. ‘Jim, I’ve written a new song. It’s about my Delilah. ’

He did sleep for a few hours that morning but, when he got up, he would spend his whole time tweaking his Delilah lyrics and trying out different lines on me. My favourite line was included in the final version: ‘You make me slightly mad when you pee all over my Chippendale suite. ’

For Joe’s birthday in 1990 Freddie despatched me to New Convent Garden market, in south London, with £ 500 to buy as many different blooms in as many different colours as possible. I bought so many I filled the Volvo completely. When I got back to the house, Freddie was waiting. Joe was out and we spent the next two hours arranging all the flowers. We filled every vase and jug we could find. The house had never seen so many arrangements at one time and when Joe got back he was bowled over.

‘Surprise! ’ Freddie said. ‘Happy birthday! ’

Later that night we all went out for a celebratory supper with the birthday boy. But Freddie and I didn’t stay long as he said he was feeling too tired.

That same month Joe told everyone in Garden Lodge that he had some bad news. He, too, was not well.

‘You mean you’re HIV? ’ I asked.

‘No, ’ he said. ‘I’ve actually got full-blown Aids. ’

What can you say? I’m sorry? Nothing of any use came into my mind. It would be another blow to contend with in Garden Lodge. We were all worried about what the press would make of it if they discovered that Joe was also ill. We had visions of the sick headlines and guessed our house would be dubbed ‘Aids Lodge’. It all made us more determined than ever to pull together and stay optimistic.

Despite putting a brave face on things for everyone else’s benefit at Garden Lodge, privately I began to get very anxious about my own health. I thought I could be HIV positive as well. The more I reluctantly thought about it, the more it seemed likely. So I decided to have an Aids test but to tell no one. I did it in total secrecy under a pseudonym. On the excuse of going to see a friend, I slipped out of Garden Lodge for a day and travelled to a hospital in Brighton.

Before the doctor would agree to take a blood sample for testing I had to undergo special counselling. The full implications of proving positive were explained honestly and compassionately. I told them I realised all the consequences and wanted to proceed.

That night back at Garden Lodge I found it impossible to sleep. I had told the hospital that I could handle the news if it was going to be bad. But I wasn’t so sure in my own mind that I really could. What would I do?

A few days later I rang for the results.

‘I’m very sorry, you’re positive, ’ said the doctor. But I didn’t have full-blown Aids.

I was dazed. I didn’t tell Freddie. He had enough to cope with; my news could only upset him. I buried myself in work in the garden and workshop and put thoughts of my own future out of my mind. But the thought of it kept coming back to me each night as I struggled to sleep and stop my mind from racing.

Freddie and I went out to Syon Park one day and bought bedding plants for the garden. As Terry was loading the plants into the car, a photographer from the Sun who had been following us took a picture. It appeared the next day, with a story claiming, incorrectly, that it was the first time Freddie had been out of Garden Lodge for two months.

Whenever Freddie saw the television commercial for cat-food featuring snowy-coated Arthur he said how much he’d like a white cat. Then he dismissed the idea because he thought it would be impossible to keep such a cat clean.

I went to the pet shop in Kensington High Street one morning and in the window there were five kittens from the same litter. Each was completely white save for a few marks which were hardly noticeable.

It was as much as I could do to stop myself buying one there and then for Freddie.

I went back to Garden Lodge, put on my waders and started cleaning out the isolation tank for the koi. Joe and Phoebe came through the back door.

‘We’ve got a favour to ask you, ’ said Joe.

‘Oh yes? ’ I replied.

‘I’ve just come from Kensington High Street and …’ he began.

‘And you passed the pet shop and saw the kittens? ’ I said.

‘Yes, ’ he said. ‘They’re only £ 25 each. Phoebe and I will give you the money. Will you get the whitest one for Freddie? ’

‘Why don’t you buy it? ’ I asked.

‘We decided to ask you, ’ Joe said, ‘because if you buy it then Freddie won’t scream and shout if he’s annoyed. ’

‘I’ll go, ’ I said. ‘But only on one condition: that if Freddie does start screaming and shouting, you’ll share the blame. ’

So I set off for the shop at once and hoped to get back to the house before Freddie got out of bed.

I drove to the shop in the Volvo. There were only three kittens left. I picked one out, drove back to Garden Lodge and slipped the kitten into my jacket as I walked in. Freddie was in the garden, so I walked slowly towards him, beaming. Freddie scowled at me.

‘You bastard! ’ he said. ‘You’ve got another cat, haven’t you? ’

‘How did you know? ’ I asked.

‘His tail is sticking out from under your jacket! ’ he said. I took the kitten from my jacket and put her on the ground. Freddie bent down, stroked her and couldn’t resist picking her up. Freddie quickly christened our sixth cat. ‘We’ll call her Lily! ’ he said. So Lily it was.

Although he adored the new kitten, he wondered whether her arrival would upset the other five cats. Oscar was a cat who preferred his own company, and the arrival of the latest kitten proved to be the final straw. Increasingly he would roam off to visit other homes in the area and adopted one neighbour especially. He even started sleeping out at night, but Freddie didn’t mind.

‘If Oscar’s happy, then that’s all that matters, ’ he would say.

Freddie’s health continued to deteriorate. He was now very thin and found it difficult to sleep, so I decided to move to my own room permanently. Some nights I would still sleep with him, but usually I just lay next to him on top of the bedclothes. He’d snuggle up next to me for comfort. Freddie nicknamed my new bedroom the Ice Box as I slept with the window wide open, even in the middle of winter.

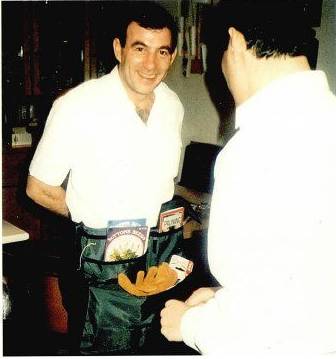

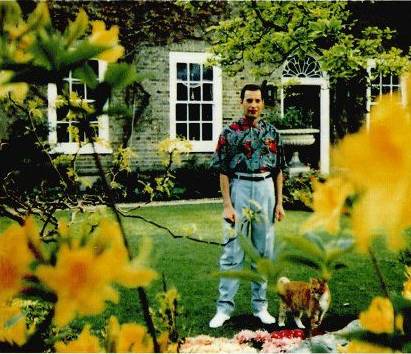

A typically comic birthday present – a gardener’s apron. Freddie was beside himself with laughter.

A typically comic birthday present – a gardener’s apron. Freddie was beside himself with laughter.

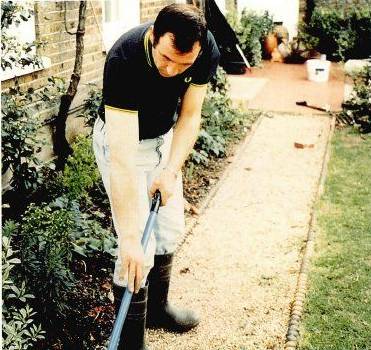

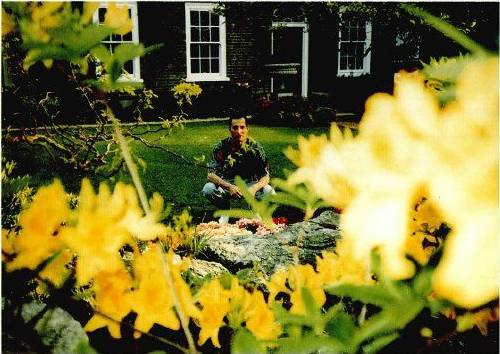

The gardener at work in Garden Lodge.

The gardener at work in Garden Lodge.

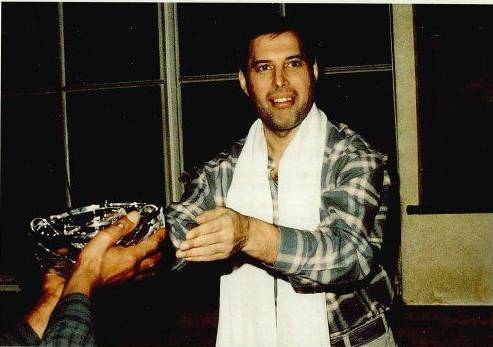

For Christmas 1989 I gave Freddie a silver cut-glass caviar bowl worth its weight in the stuff.

For Christmas 1989 I gave Freddie a silver cut-glass caviar bowl worth its weight in the stuff.

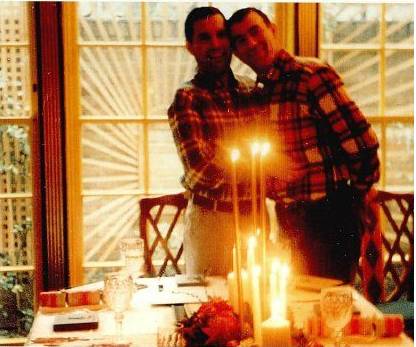

Boxing Day 1989 in the dining-room at Garden Lodge, wearing matching his-and-his shirts.

Boxing Day 1989 in the dining-room at Garden Lodge, wearing matching his-and-his shirts.

New Year at Graham Hamilton’s home. Left to right: Freddie struggling with a party-popper, Mary and our host.

New Year at Graham Hamilton’s home. Left to right: Freddie struggling with a party-popper, Mary and our host.

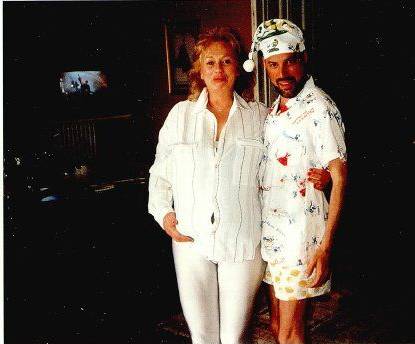

Barbara Valentin and Freddie the night he wrote the song ‘Delilah’, dedicated to his favourite cat.

Barbara Valentin and Freddie the night he wrote the song ‘Delilah’, dedicated to his favourite cat.

The two of us with Barbara Valentin in Switzerland, 1990.

The two of us with Barbara Valentin in Switzerland, 1990.

A break during filming for Breakthru in Cambridgeshire, Queen’s first ever outdoor video shoot.

A break during filming for Breakthru in Cambridgeshire, Queen’s first ever outdoor video shoot.

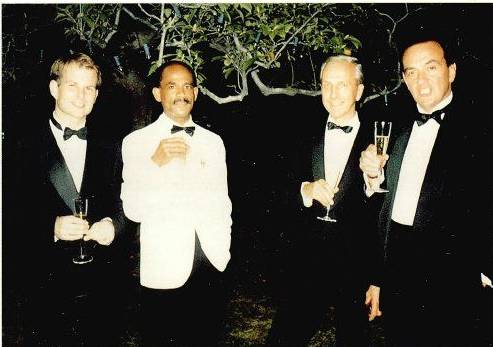

The last birthday Freddie ever celebrated was in September 1990 – a grand, dressy affair held at home.

The last birthday Freddie ever celebrated was in September 1990 – a grand, dressy affair held at home.

Left to right: Mary, Freddie and Barbara during his last lavish birthday supper. I sat opposite.

Left to right: Mary, Freddie and Barbara during his last lavish birthday supper. I sat opposite.

Freddie’s birthday, 1990. Left to right: Tony Evans (a friend of Joe’s), Trevor ‘B. B. ’ Clarke, Freddie’s doctor Gordon Atkinson and Graham Hamilton.

Freddie’s birthday, 1990. Left to right: Tony Evans (a friend of Joe’s), Trevor ‘B. B. ’ Clarke, Freddie’s doctor Gordon Atkinson and Graham Hamilton.

Freddie’s last Christmas, 1990, with Joe and his bird.

Freddie’s last Christmas, 1990, with Joe and his bird.

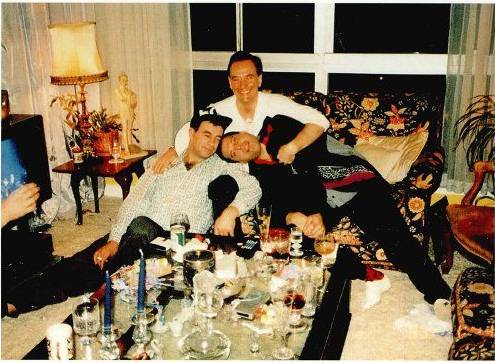

Collapsing at New Year’s Eve – the two of us with Graham Hamilton in 1989.

Collapsing at New Year’s Eve – the two of us with Graham Hamilton in 1989.

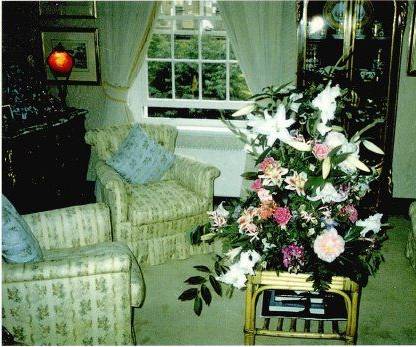

A typically lavish flower arrangement in Freddie’s bedroom. He’d call ‘cooee! ’ to me every morning from that window.

A typically lavish flower arrangement in Freddie’s bedroom. He’d call ‘cooee! ’ to me every morning from that window.

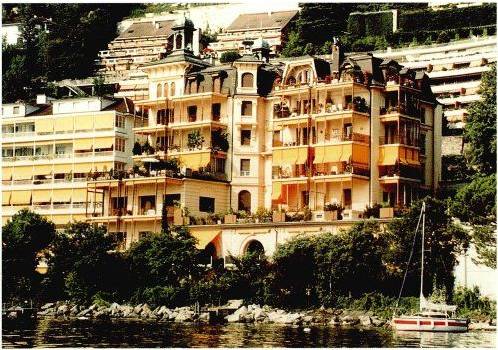

Freddie’s flat in Switzerland (the top floor of the building on the right). The last trip we made was in October 1991 and I know that’s when he decided his battle against AIDS was over.

Freddie’s flat in Switzerland (the top floor of the building on the right). The last trip we made was in October 1991 and I know that’s when he decided his battle against AIDS was over.

Freddie in the spring of 1991, looking frail and thin. This was the last time he posed for a photograph.

Freddie in the spring of 1991, looking frail and thin. This was the last time he posed for a photograph.

Freddie Mercury – my man!

Freddie Mercury – my man!

One Sunday he got up and went downstairs to discover I hadn’t got out of bed. I had the flu. He came to see me, got into bed with me and cuddled up. He kissed me.

‘Oh, you poor thing, ’ he said.

He certainly didn’t seem worried about catching flu from me. We were all conscious of his need to avoid any infection and especially colds and flu as they might prove fatal, but that day he didn’t worry about himself at all. He didn’t catch the flu from me and remained resilient.

It was while he was nursing me through my flu that Freddie decided it was time he did something about my room. He settled on the idea of commissioning contemporary Biedermeier-style furniture to be made for me by a company in Chelsea. He would design a coffee table, then a bed surround, himself. He flicked through books on Biedermeier to get ideas and started outlining his thoughts for the coffee table on a sketch pad. It looked wonderful. It was round and two-tiered. The legs were round ebonised wood balls decorated with little gold stars. The bed surround looked great, but Freddie felt it needed a few of his finishing touches. He returned with his bag of ormolu fittings and found a few large ones to decorate it. Freddie also bought me a new looking glass and three antique Biedermeier chests of drawers. A few weeks later he reserved more pieces of furniture from the supplier.

When he sent Terry to pay and collect them he proved he’d learnt at least something from me.

‘Don’t forget to ask for a discount! ’ he said.

When I moved into my own room permanently I left all the pictures on my side of Freddie’s bed because I didn’t want him to feel that I had moved out for good. The only thing I took with me was a little Cartier alarm clock. As time went on, Freddie started moving some of the photographs into my room one by one.

That move into the Pink Room also marked the point from which almost all normal sexual relations ended between us. It was clear that sex was no longer a pleasure for him but an exhausting ordeal instead. So we settled for the next best thing: gentle kissing and heart-felt cuddles. Those cuddling sessions would be as rewarding in their way as any sex we ever had.

Freddie’s medication for Aids took a new turn when he was fitted with a small catheter on his chest below his left shoulder. It had a small rubber stopper and the whole thing was so small it was barely noticeable. It certainly never interfered when we cuddled up to each other. The catheter made it simpler for Freddie to be given medicine intravenously. More importantly, it allowed him to keep on the go. By slipping the medication in his pocket and hiding the tube leading to the catheter, he could walk around and even go out.

Previously I had helped Joe and Phoebe give Freddie some of his medication. He had to take a white powder mixed with water, so I’d fix those for him or get out his pills. But once he went on to intravenous medication and had the catheter fitted, everything became much more complicated.

It was suggested that I might like to help administer the medicine intravenously, but I asked to be excused. I didn’t want to take on the responsibility. And there was also a risk of infection. My job entailed working outside, often up to my arms in muck in the flower beds or up to my waist in filthy water in the koi pool. The garden was a breeding ground for all kinds of germs. If I was to give Freddie his medication every few hours, I would have to be forever scrubbing up. Even Joe, clean as he was since he was working in the kitchen all day long, spent half an hour each time sterilising his hands and arms. I was worried that I might not scrub up thoroughly enough. It was an unnecessary risk.

Freddie understood entirely and didn’t seem at all put out by my decision.

As Freddie’s health continued to deteriorate, I used to have a quiet word with Mary. I reassured her time and again that I would always be there for her. If there was ever anything she needed she had only to ask.

In the summer, quite out of the blue, Freddie increased my wages from £ 600 to £ 1000 per month. Sadly, my wage rise was the reason for an argument between Freddie and Mary.

The accountants were on holiday, so Freddie had to sign the monthly pay cheques. I had never questioned how much I was paid. I knew that Joe and Phoebe were paid more, but they were on duty twenty-four hours a day. I never wanted to know exactly what they were paid; it was none of my business. I was just the boyfriend. I was happy with my lot. I would have tended Freddie’s garden whether or not I was paid. I loved to watch the simple pleasure it gave him.

The day Freddie signed the cheques, I was in the koi pool in my waders. He called me into the house and I went to the front door where I tried to kick off the waders.

‘Oh, leave the bloody things on, ’ he said. ‘Come on over here. I want you to give me a big cuddle. I’ve got some news for you. ’

Sostill in my waders, I walked over to him and we hugged.

He said: ‘You won’t get it this month, but you’ll get it next. You’re getting a pay rise. ’

Then Freddie said something which would prove very important to me in the months ahead. It was always understood that ownership of the house once he had died would technically pass to Mary. However, he said he hoped I would stay living there as long as I liked and reiterated that it was my home as much as his. He added that, if I wanted to move out, he had made Mary promise that I could have whatever I wanted from Garden Lodge.

I was very relieved, but I didn’t like talking about such things so coldly.

‘I don’t want to hear about you dying, ’ I said. ‘And if you want those wishes carried out, write them down. ’

During the year Freddie gave me several things for our retreat in Ireland, which was now finished and ready for decorating. Furniture deemed to be surplus to requirements was stored in the attic at Garden Lodge.

‘If there’s anything you want for our home in Ireland, then help yourself, ’ he said. Then he came with me to look. Among other things, we sent back to Ireland his old double bed from Stafford Terrace and two Victorian bedside tables.

Freddie kept many possessions he didn’t have space for in storage. So he decided that summer that it was time to get everything back to Garden Lodge to share out among the family.

When the storage chests arrived at Garden Lodge I was away in Ireland for a few days. They had been spread out on the lawn and Freddie dived into them, deciding who should get what. Joe, Phoebe, Mary and the two maids shared most of the contents, mostly knick-knacks and old designer clothes.

When I got home Freddie told me some of the things he’d come across.

‘I haven’t left you out, ’ he said. ‘There’s another trunk which no one has touched. That’s yours. ’

When I later opened up the trunk there were hats and ornaments. Then I found the original lyrics for his most famous song: ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. They were handwritten by Freddie on a sheet of A4 lined paper. I left everything in the trunk, including the lyrics, and stored it in the workshop for safe-keeping.

I was in the workshop one afternoon trying to mend an antique silver photograph frame treasured by Freddie’s parents when I had an accident with an electric plane. I took a chunk out of my finger and there was blood everywhere. I made for the kitchen where I found Phoebe and Joe. Joe was always squeamish at the sight of blood.

‘Have you got any big plasters, Joe? ’ I said.

‘What have you done? ’ Joe asked.

When I showed him my finger he gulped. This would need more than a sticking plaster.

‘You’d better go to hospital to have that stitched, ’ he said.

I dismissed it as a scratch and Freddie came in.

‘What’s all the noise about? ’ he asked.

Joe said: ‘Jim has cut himself badly but doesn’t want to go to the hospital. ’

Freddie looked at the wound and agreed with Joe and Phoebe that it needed hospital treatment. When I said it was a fuss over nothing he got annoyed.

‘All right, please yourself then, ’ he said. But to save argument I went to the hospital, and ended up having two stitches. It was much more serious than I had thought.

In the end I did finally fix the frame for Freddie’s parents. Around that time I was making another of my tables as a present from Freddie and me to chauffeur Graham Hamilton and his friend Gordon. So Freddie blamed them for my accident!

That summer Freddie and I nearly parted company after a nasty argument about nothing. For some reason I upset Freddie and we had a fight. These things would usually blow over in a day or so, but this time it dragged on for days.

I went to work, as usual, in the garden and during the morning Mary and Freddie came out into the garden and sat talking near the pool. Later, when I went back in the house, the air was decidedly frosty. Freddie kept his distance.

The next day things were no better. I was in the garden and Joe, looking most uncomfortable, told me the news.

‘Freddie thinks it would be a good idea if you left, ’ he said.

I was flabbergasted. I still didn’t know exactly how we had come to fall out, but Freddie had the drawbridge up and the portcullis firmly down.

‘Fine, ’ I said. I sounded calm but I was really quite distraught. ‘If that’s the way he feels, well, OK, ’ I said. ‘But I need time to find myself a place to live. ’

The next day I got another message, this time from Mary, that when I’d found myself alternative accommodation I would still be welcome to work six days a week as the gardener at Garden Lodge. She told me I could not have the use of the Volvo Freddie had given me for my birthday. I’d be permitted only an hour for lunch and my hours would be 9am – 6pm.

The only thing I could think about was whether I could afford somewhere to live, so I said: ‘When I find my own place, I want my wages reviewed. Gardeners in central London are getting an average of £ 12. 50 an hour. ’ I was on about £ 3.

I found myself a flat, a short six-month lease in Hammersmith Grove, which had been advertised in Loot with the unusual tag ‘To share with Sir Charles’ – a cat. The owners needed references, so I asked Mary whether she would mind speaking for me. That afternoon I was in the conservatory and got word from my new landlord that my references were fine and that I could move in immediately.

Freddie came up to me.

‘You don’t want to go, do you? ’ he said. ‘I don’t want you to go. ’

‘But I was under the impression you did want me to go, ’ I said. I was puzzled.

‘I was just angry over something, ’ he said. As we talked it over it became clear that even he didn’t remember how the argument had started and nor did anyone else. What I was so sad about was how my friends at Garden Lodge had seemed quite happy to see me go.

That night in the bedroom, lying next to Freddie, I asked him about the others. ‘Well, whose advice did you take? ’ I said. ‘I know they’ve all been giving you advice over the last few days. Who did you listen to? ’ I was determined to find out who it was who had been making trouble for me at Garden Lodge.

‘I took my own advice, ’ he said and he wrinkled his face as if to say ‘subject closed’. I asked him why he’d let it get so out of control, but he wouldn’t answer. He asked me to forget the whole thing. It wasn’t easy. I was extremely hurt and depressed by what had happened. I couldn’t imagine who would get him so worked up over nothing.

Elton John and Freddie had fallen out with each other years ago, but by Live Aid they were back on good speaking terms. That summer Elton started coming to the house and he became one of Freddie’s few regular, trusted visitors until the very end.

The first time Elton came for Sunday lunch was a day to remember. As we were laying the table Joe told me I was sitting at the end of the table with Freddie on my left and Elton on my right.

‘So don’t put salt on your food! ’ he said.

‘Why ever not? ’ I asked.

‘You’ll see, Elton will do it for you! ’ he said.

Elton wore a tracksuit and baseball cap, which stayed on his head for the entire visit. He was fairly rotund then, but on a strict diet. He didn’t have any meat, just vegetables. Nor would he drink anything but water. When we started eating I soon discovered what Joe had meant. Elton liked his seasoning and he shook the salt so vigorously over his plate that he saved me the trouble of putting it on mine.

In the autumn Freddie told Joe his right leg was playing him up. This was the same leg that had the painful open wound at the side of the calf. It had always been troublesome to him. Before we met he’d broken the same leg larking around in a Munich gay club. Joe went weight-training and suggested some exercises for Freddie to try. I turned on my heel and went off to order Freddie a top-of-the-range exercise cycle. When the bike arrived two weeks later Freddie was still having problems with his leg. Freddie loved it at first, but sessions on it were to be no more than a passing fad. Joe and I struggled to carry it to the minstrels’ gallery, and from time to time Freddie would do five or ten minutes on it under Joe’s supervision.

Freddie’s birthday in September 1990 was a lavish, dressy affair, an haute cuisine dinner party held at Garden Lodge. It was attended by some twenty guests, mostly couples. Mary was there with Piers, Dr Gordon Atkinson with his friend Roger, chauffeurs Graham Hamilton and Gordon, Jim Beach and his wife Claudia, Terry and his wife Sharon, Mike and Linda Moran, record engineer Dave Richards with his wife Colette, Dave Clark, Trevor Clarke, Barbara Valentin, Peter Straker, Joe and his friends Tony Evans, Phoebe and me.

This night was to be the last year Freddie celebrated his birthday with any kind of bang. To ensure it was a night that everyone would remember, Freddie gave each of us a memento of the occasion from Tiffany and Co, a present left on each place setting.

When Freddie penned the song ‘I’m Going Slightly Mad’ it was after another through-the-night session with Peter Straker. Freddie explained he had the phrase ‘I’m Going Slightly Mad’ on his brain and told Peter what sort of thing he wanted to say in the song. The inspiration for it was the master of camp one-liners, Noel Coward.

Freddie set about with Peter trying to come up with a succession of goofy lyrics, each funnier than the last. He screamed when they came up with things like ‘I’m knitting with only one needle’ and ‘I’m driving on only three wheels these days’. But the master-stroke was: ‘I think I’m a banana tree’. Once that came out there was no stopping Freddie and Straker – they were then in full flow. I went to bed to fall asleep listening to their laughter wafting upstairs.

It was while I was away in Ireland for a few days that Freddie and Peter Straker fell out and the rift was never to be mended. Peter was noticeable by his absence, particularly at weekends when before he would invariably come round for a drink or a meal. I asked Freddie why we hadn’t seen anything of him.

‘He upset me at Joe’s Café one day, ’ he said, but refused to say what had happened. So I asked Joe and Phoebe.

Apparently, Freddie had arranged to meet Peter for lunch at Joe’s Café in Knightsbridge. When he arrived, a little late, he appeared to be drunk. The restaurant wasn’t a regular haunt of Freddie’s and he felt that Peter had shown him up in public. Freddie decided he didn’t want to be associated with him again.

But looking back on it, Peter shouldn’t feel too awful about what happened. Freddie’s behaviour at the time was increasingly guided by his failing health. He may even have been a little jealous of Peter, who could still treat life as one long party just as Freddie had once done. It wasn’t only Peter who got the cold shoulder at that time. Barbara Valentin also drifted out of sight, as did Graham Hamilton and Gordon.

Relations cooled between Freddie and Gordon because Gordon couldn’t hold his tongue. Freddie expected total loyalty and discretion from those around him. When Graham or Gordon drove Freddie, they’d drop the names of the other VIPs they had had in the back of their car. Freddie believed that they must also talk freely to their other passengers about him.

The final straw came when I went out for a drink one night to Champions, a gay pub in Notting Hill Gate. Gordon was in the pub and came over to say hello, introducing me to a young friend drinking with him. A little later I left and walked to the nearby Gate Club, a gay club.

After I’d been there about half an hour, the young man Gordon had introduced me to arrived and made a beeline for me.

‘I know everything about you, ’ he said. ‘I know you’re Freddie Mercury’s boyfriend. ’ He went on to tell me bits and pieces of gossip he’d learnt from Gordon.

I was speechless. He was a total stranger and he knew some very private things about us.

‘Who told you all this? ’ I asked, though the answer was obvious. I left the club at once and got home about midnight. Freddie was wide awake in bed.

‘You look livid. What’s wrong? ’ he asked. I told him what had happened and he shook his head.

‘Right, ’ he said. And we didn’t see much of Graham and Gordon after that.

In November Queen signed a new multi-million-pound record deal which Jim Beach had negotiated in America with Hollywood Records, owned by the giant Walt Disney Corporation. It placed the band in the enviable position of having Disney’s finest animators, using state-of-the-art techniques, at their disposal to help make their videos.

The same month Freddie tried to ban the Sun from Garden Lodge after the headline ‘It’s Official! Freddie Is Seriously Ill’ appeared. The paper reported Brian May’s remarks that Freddie was sick. ‘I never want to see the Sun in here again, ’ he said. But the ban didn’t last. I was the one who bought the newspapers and flicked through them to take out anything I thought would upset Freddie. I’d tell him the newsagent had run out of that particular paper and leave it at that.

The staff party for everyone at the Queen office in 1990 turned out to be the last. The band never showed the staff their videos ahead of their release, but this year they made an exception and showed the extraordinary ‘Innuendo’ video, which had been made with all the latest Disney animation techniques.

The video was the creation of the Torpedo Twins, Rudy and Hans, and the animation had been painstaking and slow. The results were remarkable. It was later deemed too controversial for America, because this was the time of the Gulf War and the record company was sensitive about the song’s pacifist theme. Every day new edits of the video would keep arriving for Freddie to view. Eventually it was re-edited, omitting letters from words in the Koran, the sacred book of Islam.

For Christmas I bought Freddie some antique coloured glass goblets, but I almost blew the surprise. In a shop window I spotted six glasses with clear stems which, when I took a closer look, turned out to be a deep red colour. When I got them back to Garden Lodge I bumped into Freddie. He asked why I looked so pleased with myself and I stupidly showed him. ‘This is your Christmas present. Have a look, ’ I said. Then I put them away in a cupboard.

Around noon on Christmas Eve I set off to buy myself a pair of denim jeans in Earl’s Court. I felt furious with myself for having shown Freddie his present. As I passed the little antique shop, the owner was just unlocking and noticed me.

‘Those glasses you bought, ’ he said.

‘Yes? ’ I answered.

‘I meant to say when you bought them, I’ve got another half dozen inside, ’ he said. ‘They’re part of a set of twelve. ’

‘How much? ’ I asked. He offered a slight discount, and I bought them. I raced back to Garden Lodge, kept well away from Freddie, wrapped them up and placed them under the tree.

On Christmas morning I woke up with excruciating toothache. It was so bad I had to find an emergency dentist and he took my tooth out.

Like me, Freddie loathed dentists. He went for a check-up once a year. He was in both agony and ecstasy when being worked on by the hygienist, because he loved her aggressiveness when she was at the job. He would come out afterwards and say: ‘She really gets at them! ’

Freddie’s teeth protruded because other teeth had grown behind his front ones. They should have been taken out when he was a child, but it hadn’t happened. After he became successful he said he’d have them fixed, but the truth is he wasn’t vain enough to bother about them. And he knew his teeth were his trademark – the one thing that caricatures of him always made a point of.

Although his teeth were so prominent, I think he had a lovely smile. He became self-conscious and embarrassed only when he was having a really hearty laugh – when he guffawed like a donkey and showed all his teeth off. Then his hand would fly to hide the lower part of his face.

After Christmas lunch we went to open our presents. I took my present for Freddie from underneath the tree and handed it to him. As he tore the paper off and spied the dark red goblets beneath, he looked up at me.

‘These are in the cupboard! ’ he said.

‘No, they’re not, ’ I told him. ‘These are another six. ’

They were given pride of place in a display cabinet.

Freddie was now beginning to become very frail, but 1991 started terrifically for him in musical terms. The release of the single ‘Innuendo’ in the middle of January took him and Queen right back to the place they deserved, the top of the charts. The album came out in February and also shot straight to the top.

On Valentine’s Day Freddie was out of the house recording the video to ‘I’m Going Slightly Mad’, which would be their next single release. But that didn’t stop Freddie playing a joke on me. The cats and I had Garden Lodge to ourselves, as Phoebe was out and Joe and Terry were with Freddie at the shoot. The phone rang. It was Terry, asking if Phoebe had ‘got what Freddie wanted’. Just then Phoebe came in and I passed the phone across. Freddie came on the line and I heard Phoebe tell him: ‘I’ve only got one of them. ’

When Freddie got home, at about 8pm, I was sitting in an armchair alone in the lounge, with the hallway door closed. When he arrived there were whispers in the hall, then a flurry of activity. He came in carrying a large package wrapped in brown paper.

‘Surprise! ’ he said, handing me the large, heavy, oblong shape.

‘What is it? ’ I asked.

‘It’s a surprise! ’ said Freddie, bright-eyed. I then unwrapped a beautiful gilt-framed Victorian oil painting that I’d noticed a day or so earlier in a Sotheby’s auction catalogue. Its subject was two small kittens playing with a snail on a garden path and it was titled Surprise.

‘I know exactly where we’re going to put it, as well, ’ added Freddie.

‘Where? ’ I asked.

‘You can shift that picture there, ’ he said, pointing to a part of the wall which could be seen from all angles. It stayed there for a while, but Freddie had really bought it with the Irish retreat in mind.

Freddie also bought a second picture. It was massive, and the only picture of a man that he bought. It was of a young boy looking radiant and strong as he stood on life’s threshold. It was sent off immediately for essential restoration work, and we didn’t see it for some months.

Freddie was very weak for the filming of the video for ‘I’m Going Slightly Mad’. He had to be caked in make-up and wore a thick black wig.

Because he looked so different, when I turned up one day to take a look I didn’t recognise him. There were also some penguins there for the shoot and in quiet moments Freddie took himself off to be with them and give them water. Under studio lights they were baking and, ill as he was, he was only concerned for their welfare.

‘It’s far too hot for them, ’ he complained. It was really a distraction to keep his mind off his own problems.

Freddie decided he wanted to buy a place in Montreux. He took some of us to the Duck House for a holiday – including Mary and baby Richard and Terry and his family. One day we all went off to look at a serene fifties’ chalet-style lake-house with its own moorings and, what I fancied, a garden. But it wasn’t suitable; because of the security we really needed a flat. And we wouldn’t be living there for most of the time.

Then Jim Beach found a three-bedroomed penthouse flat in an exquisite building called La Tourelle. We flew over to see it. It was parquet-floored throughout with a spacious sitting room, large windows and a balcony looking across the lake and city. There was also a second, smaller, cosier sitting room, and at the back a kitchen and three bedrooms – for Joe, Freddie and me.

When I got back to London I received an urgent phone call from my sister Patricia. She said that for months the Daily Mirror had been trying to track down the location of our Irish hideaway. They had offered £ 1000 to the man who had transported several pieces of furniture over for us to give them the address. The paper was under the impression that they had a hot exclusive: Freddie Mercury had secretly moved to Ireland to hide from the world. Instead they settled for ‘revealing’ to my family that I was gay. My family already knew and couldn’t care less. The press were quickly sent packing.

One time when I got home from another flying visit to Ireland I sat in the kitchen with Freddie, showing him the latest photographs of the bungalow’s progress. It was turning out to be monstrous, the kind of thing Prince Charles might call a carbuncle. But Freddie was pleased with the way it looked, and he said how much he would like to see it for himself.

‘Well, why don’t you? ’ I said. ‘We can get an early morning flight out of Heathrow. We’ll be in Dublin by ten and it’ll take another couple of hours. ’

‘Will I have to meet all your family? ’ he asked.

That’s how shy he was.

‘No, you won’t have to meet the family, ’ I told him. ‘The only one you might meet is my mother. ’

Freddie knew that that wouldn’t be a problem. He thought for a moment and got very interested in the idea. He suggested that perhaps we could hire a helicopter to get us there even more quickly, and I made some enquiries.

But a few days later Freddie’s enthusiasm fizzled out. Ireland was unknown territory to him and he would find that hard going. And his illness was making him weaker and more tired than he was letting on. He wasn’t strong enough for a six-hour round trip anywhere. It was enough just to find the will to carry on.

He never did set foot in the bungalow, but it feels like he’s been there. He followed its progress so closely at all stages that I see and feel him in every room.

Around April 1991 Joe became depressed about his Aids. He poured out his heart to Freddie, and said that he worried that when Freddie died he wouldn’t have a home any more. Freddie’s compassion kicked in at once.

‘Well, ’ he said. ‘You find a house and I’ll buy it for you. ’

A few weeks later Joe found a small house in Chiswick which Freddie bought for him.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|