- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

A RARE DECEIT

February the 14th 1986 was our first Valentine’s Day together. I ordered two dozen red roses for ‘FM’ to be delivered to Garden Lodge in the morning while I was at work. But Freddie turned the romantic tables on me. The hotel’s florist came into the barber’s shop around noon with a beautiful bouquet of two dozen red roses.

Maria, my assistant, screamed out in delight: ‘Oh, they’re for me. ’ But hers wasn’t the only face which fell to the floor as the florist explained: ‘No, in actual fact they’re for Jim! ’ The customer in my chair looked on in amazement as I went bright scarlet with embarrassment. I opened the card and it simply read ‘F’.

Freddie’s friend Dave Clark, the drumming star of the sixties group the Dave Clark Five, was staging Time, a rock musical, at the Dominion Theatre, starring Cliff Richard and a hologram of Laurence Olivier. Dave asked Freddie to write two songs for the show, one of them the title song, ‘Time’.

The show was due to open on 9 April and Freddie was invited to the celebrity opening night. He wanted me to go with him. Weeks ahead of the night, Joe was asked to buy smart black dinner suits and shiny patent leather shoes for himself, Phoebe and me.

Ironically, the opening line of Freddie’s centrepiece song ‘Time’ was ‘Time waits for no man’. But time almost ran out between Freddie and me before we even got to that opening night. I discovered he was being unfaithful again. While I’d be at home most nights, content to watch television and get to bed early, Freddie continued going out alone until late. Some nights he went out and never came home at all. His excuse was that he’d stayed over at Stafford Terrace. I heard different. Friends whispered they’d seen Freddie openly playing the field.

I was aware that Joe always knew where Freddie was. I woke up one Sunday morning at about nine. Freddie had, as usual, stayed out the whole night. When Joe came down he made straight for the door, and I followed at a safe distance. He led me to Freddie, who was, exactly as he had said, in the flat in Stafford Terrace.

Joe went in through the front door and, about twenty minutes later, re-emerged with Freddie. But then I noticed a third person, a young guy, slipping out of the door and off down the road. I concluded that the gossip about Freddie was true.

I dashed back to Garden Lodge ahead of Joe and Freddie. When they arrived I said nothing. This needed a plan. I decided not to try curtailing Freddie’s activities, but to have some fun of my own. I asked Freddie if he’d mind if I went for a drink to my old haunt, the Market Tavern. He said it was fine and arranged for Terry Giddings, his new chauffeur, to drive me over there.

At the Tavern I had a few beers and got talking to a few old friends. They all said the same – I looked miserable.

‘Here, pop this into your mouth, ’ said one, passing me something.

‘What is it? ’ I asked.

‘Doesn’t matter what it is, ’ came the reply. ‘Just pop it into your mouth. It’ll cheer you up. ’ I could do with being cheered up, so without thinking I swallowed the pill. It was a tab of acid. Soon I was quite disorientated. The next thing I knew I’d left the Tavern with my friends and we were in Heaven.

No matter how much I had to drink, I never lost control of myself. But with acid I completely lost my bearings and turned into a zombie. At Heaven I met an old friend, Jay, whom I hadn’t seen for years.

‘What’s the matter, Jim? ’ he asked. ‘You look strange. ’

I told him what I could remember, about starting at the Tavern, having swallowed something and now being on another planet. Fortunately, Jay took me under his wing for the rest of the night and made sure I came to no harm.

‘You’re not going back to your home tonight, ’ he told me. ‘You’ll stay at my place where you can be looked after. ’

The next morning, waking up in Jay’s flat, I had a humdinger of a headache. I assumed that back at Garden Lodge Freddie would be furious with me, so I set off for Mary’s flat, where I figured I could explain what a ghastly time I’d had and why I’d stayed out all night. Mary told me that the previous night Freddie had been on the warpath for hours and stayed up all night, talking with Peter Straker, as he waited for me to come home.

Then the phone rang. It was Freddie.

‘Jim’s here, ’ she told him.

‘Well, ’ he said, ‘tell him to get back here, pack his bags and get out. He’s to be gone by the time I get back from the studio. ’ Then he rang off.

I was homeless again. I left Mary’s flat and stopped at a payphone to ring John Rowell to ask whether I could stay in his spare room again. He said I could, for as long as I wanted.

I returned to Garden Lodge, went to the bedroom and packed all my things. Then I went to John’s flat. I came to the conclusion that Freddie and I had fallen out for good. A few days later, on the day Time opened, I got home and the phone was ringing. It was Freddie.

‘Are you coming home? ’ he asked.

‘No, ’ I said.

‘But I want you to come to the opening night of Time with me, ’ he said softly.

‘Well, you can take your friend with you. The dinner suit will fit him just as well, ’ I said.

‘Come over, ’ he insisted. ‘Let’s chat about it. ’

So I took a cab over and was met by Joe.

‘He’s upstairs waiting for you, ’ he said. As I stepped into the bedroom Freddie threw his arms around me. Without saying a word we fell into bed and made love. The first thing Freddie said afterwards was: ‘Come on back home. ’ So I agreed. Then we got ready to go toTime. Freddie made it very plain it was only me he wanted by his side at the theatre that night, and after that things settled back into a happy routine.

During the interval at the show Freddie decided he wanted to sell ice creams. But things soon got out of hand and he started lobbing the ices randomly at members of the audience. Freddie was in equally high spirits at the after-show party held at the Hippodrome in Leicester Square where he introduced me to Cliff Richard as ‘My man Jim’. Cliff’s longevity in the music business was something Freddie told me he admired. Even though at the time he’d been in the business seventeen years himself, he still felt like a newcomer next to Cliff.

When Freddie told Dave Clark how much he admired Laurence Olivier, Dave arranged a private supper with Olivier and his wife Joan Plowright. Freddie told me that over supper the conversation got around to the critics and Freddie moaned about the scathing attacks he often suffered in the press. Olivier’s response had been sublime.

‘Fuck the critics! ’ he said.

When Freddie got home that night he was more star-struck than I had ever seen him.

‘I’ve met one of the greats, ’ he said, beaming like an excited child.

Another day I got home and Freddie told me he’d had the unlikeliest of visitors who had turned up at Garden Lodge for the unlikeliest of reasons. It was Dustin Hoffman, looking for interior design ideas for one of his own homes.

The American actor wanted to commission an interior designer whom Freddie had used to carry out some of his ideas at Garden Lodge. He rang to ask Freddie if he could show Dustin some of the rooms he had worked on in the house, and Freddie was delighted. For an hour or so Garden Lodge became a show-house to beat all show-houses.

Freddie said Dustin was much shorter than he’d expected, terribly polite and rather nervous. But Freddie soon put him at his ease and gave him a tour of his handiwork and they talked about interior design, theatre and rock music. Freddie said he’d been in seventh heaven.

During the first half of the year Freddie, Brian, Roger and John were in the studio again in London and Munich, putting the final touches to their album A Kind of Magic. They would start around noon and work through for the next twelve hours. Freddie would get home from work at the earliest some time after ten, but rarely later than one in the morning. He’d bounce in and play me a demo tape of his latest song, giving a running commentary about the bits he felt still needed honing or new effects yet to be added. Best of all, some days he came in and played his tape without saying a word – it was finished and he knew it was good.

The single ‘A Kind of Magic’ came out in March and the video to accompany it was made at the then dilapidated Playhouse Theatre in Northumberland Avenue. I turned up after work one day to watch Freddie and take a look at how the video was getting on. Before long we almost came to blows when Freddie showed his jealous side.

I got used to hanging around on the sets of the video shoots, and that evening sat alone somewhere towards the back of the stalls to watch Freddie. One of the band’s drivers came over and we got chatting; eventually we went off to have a drink. When I got back to the theatre Freddie was in his caravan, parked in the street near the stage door.

He looked very angry and I knew it was best not to hang around, so I kept out of his sight until it was time to go home. In the car on the way back to Garden Lodge Freddie turned to me and said: ‘I’m disgusted with you. Who told you to bring your boyfriend in to see the video? ’

I looked at him and burst out laughing.

‘That wasn’t a friend of mine, ’ I said, ‘It was one of your band’s bloody chauffeurs! ’

Freddie could also show his sense of humour. In 1986 I got a St Patrick’s Day card from Freddie. That evening I was told I wasn’t allowed into the kitchen. Joe or Phoebe passed a cup of coffee out to me to keep me quiet. Then Joe told me dinner was ready. I made for the kitchen, but my way was barred.

‘You’re in the dining room, ’ he said. ‘Freddie’s given me strict instructions to make a special dinner for you because it’s St Patrick’s Day. ’

In the dining room the table was fully laid for one, complete with lit candelabra. And on a plate was a large juicy steak surrounded by small bowls – spuds prepared in every conceivable way: roast, sauté ed, mashed, boiled, croquette, chips, Dauphinoise, baked, and so on.

‘Freddie told us to cook every type of potato we could think of, ’ Joe said. Freddie always thought that because I was Irish I had to love potatoes. I did. I sat down and ate the most delicious dinner I can remember.

A few times during the year Freddie took me out for romantic suppers. One night I got home from work and he hugged me as usual.

‘Go and get yourself ready. We’re going out, ’ he said.

Terry drove us to one of Freddie’s favourite places to eat, an Indian restaurant called Shazan’s. But we went alone and, unusually, there were none of Freddie’s friends waiting for him. He’d requested the most romantic table in the restaurant, which was in the basement.

All through dinner he kept touching me, perhaps to see if he could embarrass me in front of the other customers. He’d reach across the table and hold my hand. When the ice cream arrived he even spoon-fed me mouthfuls. His attitude to the looks of disdain from some of the people there was ‘Fuck them! ’ But it wasn’t mine. Though he was trying to be romantic, in front of all those strangers I felt very shy and turned bright scarlet.

When Freddie and I were in private he could be particularly romantic. We never once broached the subject of how long we’d be together. We just accepted that we were and would be. Occasionally he’d ask me what I wanted out of life.

‘Contentment and to be loved, ’ I’d reply. It seemed like I’d found both in Freddie.

Another thing he’d often tell me, right up until the night he died, was: ‘I love you. ’ And it was never an ‘I love you’ which just rolled off the tongue; he always meant it.

I didn’t find it so easy to show emotion. I’d lived on the London gay scene for many years and had come to realise you can get hurt very easily when relationships end. Each finished relationship builds up a new barrier and they become difficult to break down. But, in time, Freddie tore them all down.

I think we both shared a fear of the same thing – loneliness. You can have all the friends in the world around you, yet still feel agonisingly lonely, as Freddie said time and again. We were both acutely aware that many of our gay friends were haunted by the prospect of living out their lives alone, unwanted and unloved.

Freddie’s next solo release was ‘Time’ in May. The same month Queen headlined the annual Golden Rose rock festival in Montreux. I went with Freddie on the trip and the concert was followed by a party for the band on a boat.

When Freddie arrived he was asked to pose for the photographers, and I soon realised that he actually did have some power over the press. The photo session went very well and after five or ten minutes, when they’d got plenty of pictures, Freddie thanked them, said he’d finished and it was time for the celebrations to start.

He sat down at a table and started chatting intently to singer Belouis Some, who was always changing his name and seeking Freddie’s advice on the subject. A few minutes later a sneaky freelance photographer crept up on them to try for more candid shots of Freddie. But he’d barely fired off three shots before five of the other photographers pounced on him. They dragged him away and a bit of a scuffle followed.

‘I bet you won’t see that photo in the press tomorrow, ’ shrieked Freddie gleefully. He was right. It’s also just as well that no photographs were taken during the party; what happened on the boat that night doesn’t bear thinking about. It was a riot.

The Sun did later print a photograph of Freddie taken while he was performing at the festival, which he didn’t appreciate. It showed off “Flabulous Freddie” with a slight paunch, wickedly describing it as his “midriff bulge”. When he saw the picture he looked at me and shook his head in despair.

‘It’s typical, ’ he said. ‘If I’m slim the papers say I’m too thin and if I put on a little bit of a belly they say I’m too fat. It’s a no-win situation. ’

Freddie joined the band to rehearse for their forthcoming ‘Magic’ Tour of Europe. It was to begin at the Rasunda Fotboll Stadion in Stockholm on 7 June, then continue until August, finishing with the most fantastic of flourishes before Queen’s biggest-ever British audience of 120, 000 at Knebworth Park, Hertfordshire.

As they left Britain in June, the album A Kind of Magic was released, along with the single ‘Friends Will Be Friends’; ‘Seven Seas of Rye’, Queen’s second single from 1974, which had given them their first taste of chart success, was on the B-side. The album rose to the top of the charts in Britain and over thirty other countries.

When the Magic Tour reached Paris I decided to make a surprise visit to see Freddie. It was a gamble. Although Freddie loved springing surprises on others, he hated being caught off-guard himself.

After work I went home and changed, filled a holdall and set out for Heathrow. I flew to Paris and made my way to the Royal Monceau Hotel. I asked if they had anyone staying in the name of Freddie Mercury or Queen and the receptionists just gave me a blank look. I knew I had the right hotel and guessed that the band were checked in under aliases to avoid the press and fans. (I later discovered that Freddie always booked under the name A. Mason. )

Happily, I bumped into one of the crew in the lobby and he confirmed that Freddie was indeed staying there. He and the band had gone to the Hippodrome de Vincennes for a sound-check. So I sat and waited. When Freddie returned he looked at me and said casually: ‘Oh, hello. ’

He didn’t seem surprised to see me; if anything he looked angry. Later he had a go at Joe for not telling him I was arriving; he did need to be in control of events.

The next morning Diana Moseley arrived at our hotel suite. She was the costume designer for the Magic Tour and was delivering for the first time Freddie’s campest costume, a deep red cloak trimmed in fake ermine and a jewelled crown fit for royalty. It was extraordinary to watch him as he threw the cloak over his white towelling robe, put on his crown and strutted around the room.

Freddie sashayed around regally but said something was missing. Then he grabbed a banana and used it as a microphone. He flounced about, trying to work out the way the cloak fell as he moved. He loved it. And so did all the fans that night.

As the crowds cheered, I thought: ‘That’s my man! ’

The following Saturday, 21 June, Queen played the Maimaritgelä nde, in Mannheim, Germany. At about four on the Sunday morning I was at Garden Lodge when the phone rang. It was Freddie, screaming that he’d been locked in his room and couldn’t get out. He was depressed and wanted me to fly out immediately to be with him. When I got to the hotel Freddie seemed fine, if slightly exhausted. It was nice to feel wanted.

After Berlin we went on to Munich. No sooner had we arrived at the hotel than Freddie flounced out. He’d been given a very plain, drab suite and it was not to his liking. We settled into our hotel rooms, then joined the rest of the band for dinner in a tiny café. We had a raucous meal and all got terribly drunk. I remember talking a lot to Roger Taylor’s roadie, Chris ‘Crystal’ Taylor, and Brian’s assistant Jobby. The party continued through most of the night back at the hotel.

From Munich the band went on to Zurich, but I headed back to London. On 5 July they played Dublin, where they had the only poor reception of the tour. Several drunken gate-crashers got in and started throwing things at Freddie and the others. After that night Freddie vowed that the band would never return to Ireland again. Nor did they.

Finally the band played Newcastle before returning to London for a few very special days.

Friday, 11 July and Saturday, 12 July were milestones in Queen’s career – two sell-out concerts at Wembley Stadium. It was the band’s first time back on the massive stage since their incredible show-stealing Live Aid set a year earlier, and over the two nights 150, 000 people would see them.

Freddie had recurring problems with nodules on his vocal cords, the price he paid for being a singer. That meant he toured with a small machine, a steam inhaler in which he firmly believed. He also sucked Strepsils throat lozenges all the time. On the first night of Wembley Freddie had some throat problems, but dismissed them as not drastic enough to stop the show. As always, I watched from all over Wembley on both nights.

The after-show party on Saturday was held at the Roof Gardens Club in Kensington and, because the press would be there, Freddie wanted Mary on his arm. It was a rare deceit that he was not in love with me, and he apologised for it. ‘It’s got to be this way because of the press, ’ he said.

I understood completely, and followed at a safe distance a few paces behind them.

The party was a characteristically lavish Queen affair. Hundred of bottles of champagne were emptied, and the final bill was over £ 80, 000.

The five hundred or so guests were greeted in the lifts by girls dressed in nothing more than body paintings by German artist Bernd Bauer. Plenty of famous names turned up: Jeff Beck, Nick Rhodes from Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet, Paul King, Limahl, Cliff Richard, Gary Glitter, Mel Smith, Griff Rhys Jones, Janet Street Porter and Fish from Marillion, someone I really took to.

At one point Queen took to the stage to belt out rock and roll numbers and Freddie stole the show with an unlikely partner, Page Three model Samantha Fox. He hauled Sam on to the stage and they tore into ‘Tutti Frutti’ and ‘Sweet Little Rock and Roller’. When I met her afterwards she was still shaking with excitement.

Next stop on the Magic Tour was Manchester’s Maine Road football stadium on Wednesday, 16 July, and I flew up north with Freddie and the band. For the show Mary, Phoebe and I wanted to sit in the audience. A steward escorted us to three seats. About ten minutes later three people turned up and claimed the seats were theirs. Mary flew into a rage and tried pulling rank, telling them she was Freddie Mercury’s girlfriend. It wasn’t a clever move; her remark didn’t cut any ice. In fact, she found herself at the receiving end of an unpleasant tirade from an obnoxious man. (I was later told he was Peter Moores, heir to the Littlewood’s Pools empire. ) In the end we gave up the seats and watched the rest of the show from backstage.

After the concert we were escorted through the cheering crowds of fans. At one point there was a serious risk that the band would be mobbed, so we resorted to a double-decker bus with a difference – instead of ordinary doors you got in through a custom-built ‘tunnel’. To make a quick getaway, Mary and I and some others from the team were waiting on the coach ahead of the band. When they ran on we all hurried upstairs to see the sea of cheering faces stretching back in every direction. What a send-off!

We pulled off with a police escort, sirens blazing and the night sky lit up with flashing blue lights. We had a clear run out of the city and our escort went on for miles past the city boundary. During that journey back to London I pondered the scenes I’d just witnessed. They reminded me of the newsreel footage of the Beatles being mobbed by fans in the sixties. For the first time I fully appreciated how frightening it could sometimes be for Queen, and why they needed such elaborate security arrangements to escape a mob of tens of thousands of thrilled but over-excited fans.

After the Manchester concert Freddie left with Joe for the next leg of the tour – Cologne and Vienna. Queen were playing Budapest on Sunday, 27 July, making history as the first major Western rock band to perform in an open-air stadium behind the Iron Curtain. The band decided to take a river cruise down the Danube for a few days before arriving in Budapest in great style on President Gorbachev’s personal hydrofoil.

Mary rarely accompanied Freddie on tours, but on this trip he wanted to give her a short holiday, so he invited her to Vienna to join him for the cruise. Mary was very worried about leaving Jerry, the cat she’d inherited from Freddie, so I volunteered to stay in her flat for a few days to keep an eye on him.

But I wasn’t planning on missing ‘The Hungarian Experience’, as it had been dubbed. The Queen office in London arranged for me to fly to Budapest a few days early, on the Friday. Terry and Joe were waiting for me at the airport with a chauffeur-driven car; we went directly to the hotel, where Freddie had claimed the Presidential Suite. It was magnificent, with a vast balcony, and was crowded with people including Mary, Freddie and Queen’s manager Jim Beach, Brian May, John Deacon, Roger Taylor, who was having his neck muscles worked on by the band’s physiotherapist, and paparazzo Richard Young.

After making a sound-check we all headed out for a huge Hungarian feast, with every damn thing tasting of paprika. When we returned to the hotel, I sloped off for a quiet stroll around the streets of this enchanting city before finally turning in for the night.

It was difficult enough in Hungary to buy records and cassettes, so heaven knows how impossible it would have been to buy any of the eighty thousand tickets for the concert. For most of the inhabitants of Budapest, the tickets were too expensive – they cost the equivalent of a month’s wages.

As a special treat for his audience, Freddie decided to thank Queen’s dedicated followers by singing ‘Tavaszi Szel’, a moving and traditional Hungarian song. He was only given the lyrics late on the afternoon of the show, so he spent all his time striding around the suite or balcony frantically trying to teach himself the words. They didn’t come very easily.

Queen’s presence in Budapest had set the place buzzing, and when we left for the stadium our police escort brought the city to a complete standstill. We made the twenty-minute journey at breakneck speed in the first of a fleet of limousines flanked by scores of police outriders. We screeched around corners, jumped lights and seemed to fly through the city. Terry, Joe and I were nervous about the speed, but Freddie was quite oblivious to being tossed around so roughly. He was still trying to remember the words of the Hungarian song, humming to himself and repeating the lyrics beneath his breath.

The concert that night was sensational. There were police everywhere at the Nepstadion to control the massive crowd. I watched the first half of the set from the wings; but after the interval I went out front and spent the rest of the evening lost among the ecstatic crowd. I watched my man, spellbound, from all points in the stadium. The stage was massive and Freddie used it all, exhaustively working the audience. Above the stage were vast torches belching flames, and the whole thing looked spectacular.

When Freddie came to sing the folk song, he was astounding. He had scribbled the lyrics on his hand and resorted to them openly, but it didn’t matter. As soon as the first words sprang from his mouth, the whole audience of Hungarians went wild, stunned that a foreigner had braved their most famous and difficult song. At the end the crowd erupted and, even though he was no more than a dot on the horizon, I could tell that Freddie was relieved to have got through it. Towards the end of the concert, Freddie strode out in his ermine cape and crown and the stadium exploded into total euphoria. For hours after that show Freddie was on an unstoppable high.

Next morning Joe had a slight drama. He wore contact lenses but had forgotten to bring their small cases on tour, so instead he placed them to soak in two glasses of water. He was not in his room when the chambermaid called and she emptied the glasses into the sink, flushing his lenses away.

‘Hopeless fool! ’ said Freddie. I wasn’t sure if he was referring to the chambermaid or Joe.

When I got back to Britain I read a feature by David Wigg in the Daily Express. He reported Freddie’s response to Mary’s desire to have a baby by him: he would sooner have another cat. David also reported that Freddie was unattached. Freddie always felt that keeping to this line made things simpler for the two of us, and he was right. However, he did say in the article: ‘For the first time I’ve found a contentment within myself. ’ He told me he was referring to our relationship.

Freddie felt Mary had long since become a public part of his life in the papers and knew she could deal with it easily enough. But he always tried to shield me from the press. He looked on fame as a double-edged sword.

After work on Friday, 1 August I flew to Barcelona to join Freddie. He told me he’d been interviewed by Spanish television and declared cheekily that the main reason he was in Spain was in the hope of meeting their great opera diva, Montserrat Caballé. Phoebe had converted Freddie to opera. He had a large collection of opera CDs and probably everything Montserrat Caballé had ever recorded. Freddie would spend hours listening to them and asking Phoebe to explain the characters, plots and sub-plots.

After the Barcelona concert we all went out to a fabulous fish restaurant. At one point I asked Roger Taylor how the tour was going.

‘Well, Freddie’s different this year, ’ he said. ‘What have you done to him? ’

He told me Freddie was a decidedly changed man. He’d stopped trawling the gay venues while the others went back to their hotel, and he’d stopped burning the candle at both ends.

Roger’s comment spoke volumes. I took it as a reassuring nod of approval which was very much appreciated. Coming from one of Freddie’s closest friends, and one of the band, I saw it as a vote of confidence in our affair. To me it said: ‘There has to be something serious going on here, Jim. ’

From the restaurant we went on to a stylish nightclub co-owned by a stunning-looking woman in a rather revealing dress. She decided she wanted to join our party and made a bee-line for Freddie, forcing herself between Freddie and me. Her right buttock was precariously perched on half of his chair and her left on half of mine. She then crossed her legs and, every so often, her hand slipped to her side as she yanked her hemline a little higher up her tanned legs.

‘Have you got a girlfriend? ’ she asked Freddie.

‘No, I haven’t, ’ he replied.

‘Have you got a wife? ’ she asked.

He leaned across her, put his hand on my knee and said: ‘Yes. This is the wife! ’

With that the poor woman almost died! She babbled hurried excuses and ran off into the crowd to hide.

The next date of the tour was a Sunday night in Madrid. Before we left Barcelona I arranged for some flowers to be delivered to Freddie’s hotel room in Madrid ahead of our arrival. The message on them was to read: ‘From the wife! ’

When we got to Madrid there was no sign of the flowers anywhere. They turned up several hours later and looked to be in a sorry state: a scruffy little bunch of half-dead roses. Worse still, the message said something about a ‘Whiff’. Freddie spent most of the day trying to fathom out what ‘Whiff’ meant, so in the end I put him out of his misery and told him of my intentions which had gone wrong. He burst out laughing.

Back in Britain, Queen were due to play Knebworth Park, in Stevenage, Hertfordshire, on Saturday, 9 August. It was the last concert Queen ever played. That was a corker of a day and the whole event was a great way for any rock legend to bow out from live performances. I flew up with Freddie, Brian, Roger and John in a helicopter from the helipad in Battersea. There were said to be 120, 000 at Knebworth that day, and some sources reckoned it was as many as 200, 000. The traffic jams brought the whole of the surrounding countryside to a halt. Still some miles from Knebworth, I looked out of the helicopter window on to the endless ribbons of tiny cars, sitting bumper to bumper.

‘Are we causing all this? ’ Freddie asked.

‘Yes, ’ I replied.

‘Oh, ’ he said softly, grinning.

When the helicopter landed, cars were standing by to ferry the band directly to their dressing rooms. I followed in another car and met Freddie in his room. He was always nervous before a show. In the minutes before it was time to go on he seemed to have too much nervous energy in him and would become terribly on edge. This restlessness lasted right up until the very second he hit the ramp to the stage; but once he’d seen the heads of the fans, he was fine. He was theirs.

At the other concerts I’d often go into the audience and head for the sound tower to clamber up for a perfect view. At Knebworth I couldn’t even get to the tower through the dense crowd. I milled around on the edge for most of the night. Towards the end of the concert, a familiar face approached me. It belonged to a guy I’d met in Budapest who told me he’d been granted special permission to fly from Hungary to attend the Queen night at Knebworth. I was so touched that I took him backstage to meet Freddie, and the Hungarian was overjoyed.

As always, the concert was followed by a legendary Queen party, though Freddie and the band couldn’t stay all night because the helicopter was standing by to fly us back to London. During that flight we heard a rumour that a fan had died, the victim of a stabbing. Because of the sheer numbers of fans it had not been possible to get him to an ambulance in time to save his life. When Freddie heard about this he was very upset.

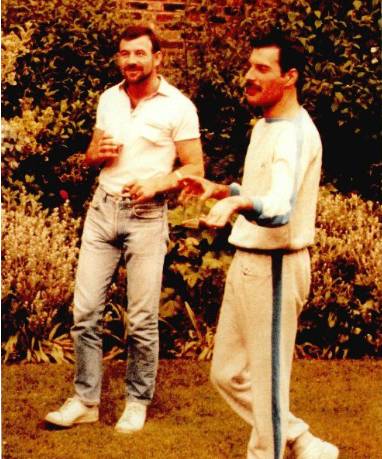

With Freddie in the grounds of Garden Lodge in 1985, the very first time he took me to see the place.

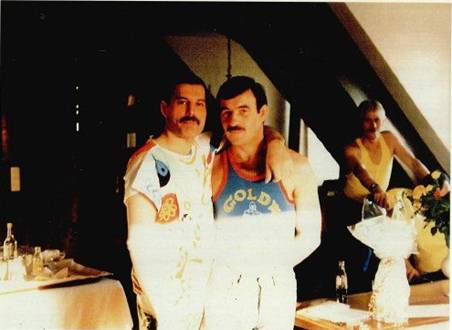

With Freddie in Munich, 1985.

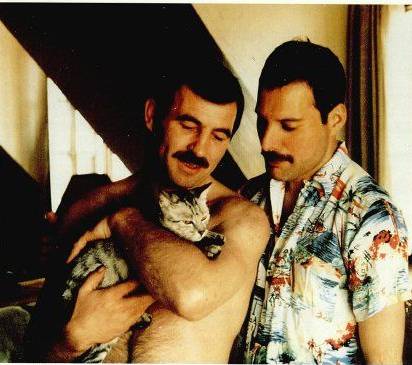

With Freddie and feline visitor Dorothy in Munich, 1985.

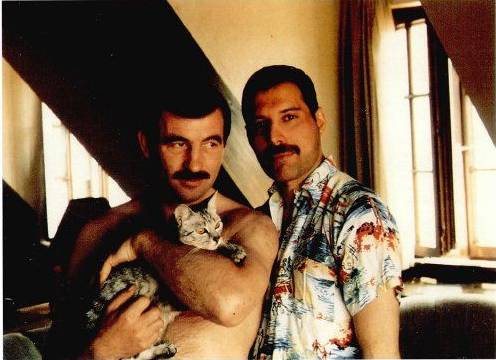

With Freddie and Dorothy.

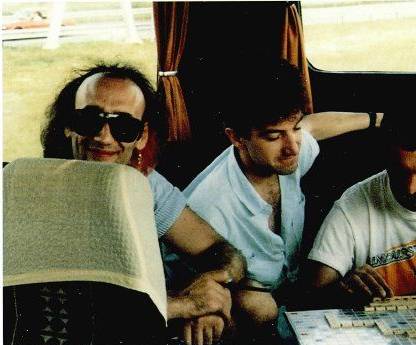

Left to right: Roger Taylor’s assistant, Chris ‘Crystal’ Taylor, with John Deacon and Freddie playing Scrabble on the tour-bus, 1986.

Banana in hand for a pretend microphone, Freddie swanned around excitedly trying out his new regalia the moment it arrived for the 1986 tour.

Freddie’s jubilant costume designer, Diana Mosely.

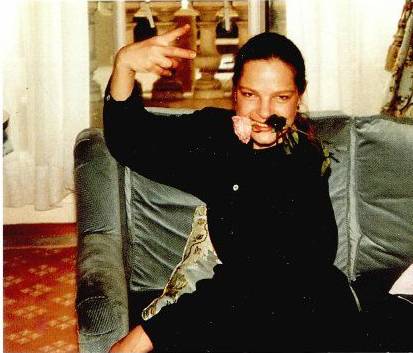

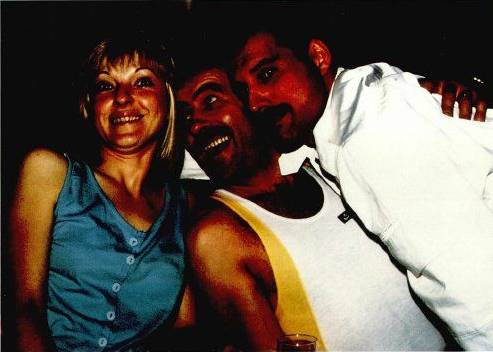

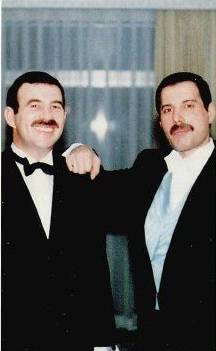

Just as Mary Austin and I posed for this picture, taken during the Magic tour, Freddie leapt on top of me.

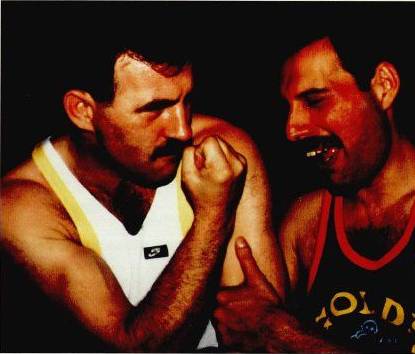

Sparring partners – Freddie and me during the Magic tour.

With Freddie in Japan for our £ million ‘holiday of a lifetime’.

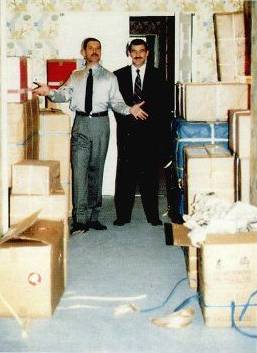

Freddie and me with just one day’s Tokyo shopping – probably worth around £ 250, 000.

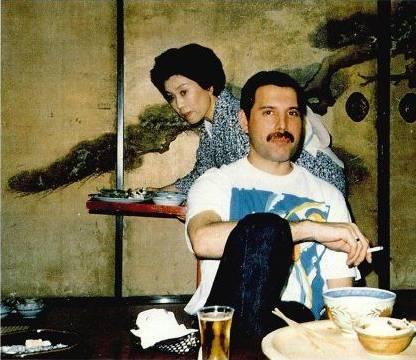

Misa Watanabe, our Japanese hostess, with Freddie.

Where’s my dinner? Freddie hungry for his supper.

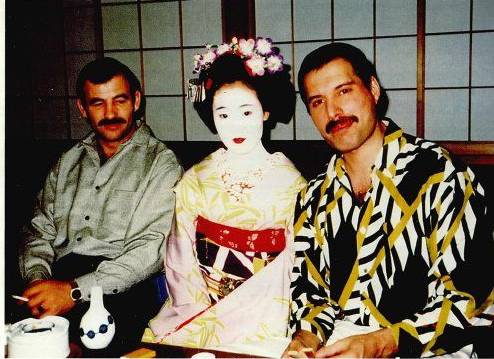

At the Geisha school with Freddie. The make-up fascinated him, so did the kimonos.

Freddie at the Geisha school.

The next morning Joe confirmed Freddie’s worst fears; it was now official. A fan had died after a knife attack. Freddie seemed very subdued but appeared to cheer up once friends arrived for Sunday lunch. When I went out for the Sunday papers I was expecting the worst from the tabloids, dreading what they would have to say about Queen’s farewell concert. To my amazement I couldn’t find a single bad word about them, despite the fan’s tragic death. The good coverage in the press cheered Freddie up a little, but the death continued to prey on his mind. He only ever wanted his music to bring happiness.

While the rest of us took the remainder of the day very slowly, Freddie had his mind on the future. Even though he’d just notched up his biggest-ever triumph in Britain, he immediately had his mind on his next project. He wanted to get back into the studio.

First, though, over the next few weeks Freddie planned to relax and do some serious socialising. He wanted to throw a fortieth birthday party for himself at Garden Lodge. Then he and I, accompanied by Joe, would go off to Japan for what Freddie promised me would be ‘the holiday of a lifetime’.

Freddie spent a great deal of time planning his birthday. He decided on a Mad Hat party and sent out over two hundred invitations for the afternoon of Sunday, 7 September. Some guests were so keen that two of Freddie’s friends from the Royal Ballet turned up a week early, complete with outrageous headgear.

I wanted to give Freddie something very special for a very special birthday: a gold wedding ring. It was to be a secret, so to discover his ring size I tried on an old battered one which Winnie had given him but was now relegated to the bottom of a bedroom drawer. It fitted my little finger perfectly, and on that basis I went off and bought Freddie a plain, flat gold band. I mentioned I was buying it to Mary, who thought it a lovely idea.

During the week leading up to the party the weather was consistently overcast. Freddie wanted his guests to have the full run of the house and garden, so we prayed hard for good weather and even considered sun-dancing. The days immediately before the party were largely spent stocking up with provisions and decking Garden Lodge from top to toe with flowers. Freddie was so meticulous that he personally oversaw every detail. Joe, Phoebe and I simply did our master’s bidding.

The garden was something of a mess, because Freddie was having a pool so that he could keep Japanese koi fish. There was still a huge hole in the middle of the garden and Freddie was concerned about guests falling in and seriously hurting themselves.

On Thursday, the night before Freddie’s birthday, several people were at the house. Peter Straker was there, which meant he and Freddie

would be up all night. Just before I went to bed, I called Freddie into the dining room. ‘I wanted you to have this first thing in the morning when you got up, ’ I said, passing him the box with the ring in it. He opened it up and tried on the ring at once. It fitted a treat. Then he kissed me and we cuddled for a minute or two.

He was never a jewellery queen, wearing little chains and twee bracelets. But he always wore the ring around the house. However, if he went out in public he’d usually slip it off. Gay or straight, a ring on your wedding finger tells the world that you’re attached. He wanted to give nothing away.

On the Saturday I was out shopping and came up with the answer to the problem of the garden hole. I bought hundreds of barbecue candles and night lights to mark out the dangerous area.

When we woke up on Sunday morning the clear blue skies promised sunshine all day. In the morning, as I placed my candles around the edge of the pit in the garden, Freddie was looking out from the window, confounded and bemused. When I came in he asked me what I’d been doing. I wanted the candles to be a surprise, so I said, ‘You’ll see this evening. ’

The party got going by early afternoon amid colourful scenes to rival any Easter bonnet parade. Every guest turned out in a hat, ranging from the conservative to the crazy. Diana Moseley had laid on several hats for Freddie, made by different designers, but in the end he settled mostly for just one, a ‘bongo’ hat sending up the fad of wobbly things bouncing around on the end of two wires. I wore a big floppy hat, made from foam and covered with flower ribbons pinched from the birthday bouquets which had been arriving all week for Freddie.

Joe’s hat was good enough to eat – a box of chocolates with real chocolates on top. And Phoebe sported one which was a tribute to Miss Piggy. Mary wore a matador’s hat speared with a sword. All the band were there with their respective partners. I remember Jim Beach, Peter Straker, Trevor Clarke, Dave Clark, Tim Rice, Elaine Paige and Susannah York all having a good time. (Wayne Sleep was also there, but it was a doomed friendship; Freddie complained that once he had had a drink too many he became ‘a right pain’ and left him off the guest list for future parties. )

I, too, had a few friends there, including John Rowell who came in a hat boasting a tiny laid-up table complete with miniature cups and saucers.

The party lasted well into the early hours but, as I had to go to work the next day, I slipped up to the bedroom and got into bed. Just as I was dozing off, I heard the door open. It was Freddie showing friends around the house. ‘Sshh, ’ he whispered, ‘my husband’s asleep. Don’t wake him. ’ A little later I heard loud screams of laughter from downstairs and knew that Freddie and Straker were in party mood. I drifted off, never believing that I would be able to sleep through the din.

When I woke up, in bed alone, I could hear voices coming from downstairs. Freddie and Straker had talked through the night and were still in a strange mood. I got up and dressed for work in my suit with a white shirt and a tie. I popped in to say hello and goodbye to them, then went into the hall to put on my overcoat. As I crossed the double door to the lounge, I overheard Freddie asking Peter Straker: ‘Who was that? ’

‘It’s your husband, darling. ’

Freddie screamed.

I still don’t think Freddie had recognised me in a suit. Even though he’d bought me two suits for my birthday, he never paid much attention to what I was wearing.

When I got home from work that night he said as much. He told me that that was the first time he’d noticed me in a suit. I took it as his way of telling me he thought I looked smart.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|