- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Chapter 48

Last time Mab had taken this walk, it had been with Francis. We’ll bring Lucy, she’d thought at the time, head against his shoulder as they looked out at the lake. She let herself sink into that dream now: Francis pointing out the flowers she couldn’t identify; Lucy running after butterflies; Mab following in a summer straw hat. Francis would have carried Lucy over the steep bits of the climb—Lucy would have allowed that. At the very end in Coventry, she’d let him pick her up. She’d been learning to trust him. She would have let him carry her all the way to the top of the lookout here.

Only now she never would.

Why. The word had been echoing through Mab’s brain for three weeks now, about everything. Why. Why. WHY.

Why didn’t you marry him at once, instead of waiting until you were sure he was a good prospect?

Why didn’t you quit working at Bletchley Park and make a home right away for him and Lucy?

Why were you so careful not to conceive a child?

Why and if. The two most painful words in existence. If she’d married Francis Gray the week he proposed, they’d have had three more months of married life. If she’d resigned from BP, she would have had her family together every night when Lucy came home from school and Francis came home from work, not spread out and waiting because war work had somehow seemed more important. If she hadn’t been so careful to avoid conception, she might have had something of Francis besides a packet of love letters.

You have more than that, she reminded herself bitterly. You have everything you ever dreamed of, Mab Gray. She’d wanted to ditch the name Churt and remake herself as a lady of means, with no whiff of scandal that she’d ever been a cheap East End slut who gave birth out of wedlock. Well, she was Mrs. Gray now, and she was certainly a lady of means: Francis’s will named her sole inheritor of his modest royalties and not-so-modest accounts. She could afford all the fine hats and leather-bound books she wanted, and no one would ever know she’d given birth out of wedlock because her child was dead.

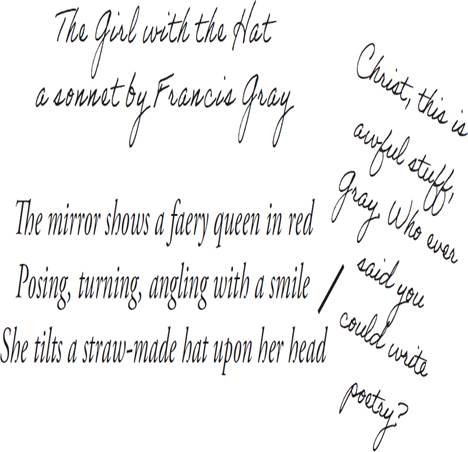

She realized that she was ripping her blue-ribboned hat to pieces and flinging them off the lookout. The ribbon went drifting down the hillside, as blue as the surface of Derwentwater, then the straw brim, then the wafty netting. In Francis’s wallet, returned to her with his effects, she had found a folded sheet of paper with a few scribbled lines in his writing:

But there were more lines, reworked and crossed out and reworked again, and at the very bottom he’d squeezed in a note: Work Lucy into the metaphor? Titania’s sprite Peaseblossom? Or is Luce more of a Mustardseed. . .

The pain clawed Mab like some hungry beast, doubling her over. It never hit when she expected it to—she’d stood entirely numb through Lucy’s funeral in London, through Francis’s here. Sometimes it crept up on her at night, leaving her sobbing, or it overcame her when she was pouring a brandy and wondering if she’d sleep if she drank an entire bottle. She never knew when it was coming, only that it would never stop. She was twenty-four years old; she’d been a mother for six years and a wife for less than one, and the pain was never going to stop.

Then she turned and saw Osla and Beth coming up the path onto the lookout.

Mab didn’t wait for either of them to speak. She pulled her head back and spat at Osla, hitting Osla’s black cashmere coat hem. “How dare you show up at his funeral, Osla Kendall. How dare you. ”

“I came for you, ” Osla whispered. “I’m your friend. ”

“You killed them, ” Mab rasped. “You let go of Lucy—you let her go, and Francis went tearing off after her—”

“Yes. ” Osla stood chalk white and shaking, but she didn’t flinch from the accusation. “It’s my fault. ”

“All you had to do was hold on to her, and you let her go. ” Mab heard her voice scaling up and choked it off. She would kill Osla and Beth right here and now if she cried in front of them. “We—if we’d got to a damned air-raid shelter—”

“You can’t blame Osla, ” Beth whispered.

“Yes, I can. ” Mab felt herself smiling mirthlessly. The smile hurt. She welcomed the pain, dug into it, ate it raw and sopping red. “I can blame everyone. ” The Luftwaffe, for bombing Coventry. Herself, for insisting Francis take them there. Francis, for stepping left instead of right to get out of the garden. “But all Osla had to do was hang on to Lucy’s hand, and she fucking let her go. ”

“I did. ” Osla’s eyes overflowed, tears streaking sooty and black down her cheeks.

“She was my daughter, ” Mab whispered. “You killed my daughter. ”

“She was your sis—” Beth began automatically, literal as ever, and then even Beth stopped dead, her eyes huge and horrified.

Osla trembled. “Oh, Mab—”

“Shut up. ” Mab was shaking, too, now. “Don’t you say a goddamned word to me ever again, Osla Kendall. Don’t you dare. ”

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|