- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Chapter 36

Darling girl, Francis had scribbled hastily on Foreign Office stationery,

I can’t get away from the office until this evening. Pop in on your family, then come back to my rooms and make yourself at home. I shall see when I can get out—hopefully not so late I cannot pin you to my exceedingly narrow bed and do a number of ungodly things to you which I have been daydreaming about, most inappropriately, during work hours. —F

Mab repressed a violent urge to curse. She would undoubtedly shock her husband’s grandmotherly landlady, who had passed the letter over and now stood in the shabby-elegant corridor looking sympathetic. “He sent the note round an hour ago, dearie. Asked me to give his lovely wife the key to his room if she wanted to wait for him. ”

I don’t want to wait, Mab wanted to shout. I want him here! Already gone May, and she had barely seen her husband at all since the Lake District. They simply hadn’t had any luck when it came to timing. First Francis had been sent to Scotland for nearly five weeks, completely out of reach, then when he came back and they had managed to line up another weekend—Mab hoarding her days off, working twelve days straight so she’d have forty-eight hours’ leave—that had been scuppered by Wren Stevens, who begged, crying, for Mab to take her shift. “Jimmy’s shipping out to Ceylon, it’s my last chance to see him! ” What was Mab supposed to say? Well, she could have said no, if she was as much of a hard-boiled egg as some seemed to think, but she didn’t have the heart. Francis wasn’t shipping out somewhere dangerous; they’d have all the time in the world once the war was done—who knew if poor weepy Stevens’s fiancé would come back alive?

So the only time together Mab and Francis had managed in the last few months had been tea in a railway café between London and Bletchley, surrounded by irritable waitresses and squalling children. They could barely hear each other over the din; conversation died utterly after a few feeble fits and starts. All they could do was hold hands over the rickety table, smiling in silent rueful acknowledgment of their situation, Mab unable to ask in the middle of the noisy café, What did you think of my letter?

Her husband had answered that spilling of her soul with a short letter of his own: I think you are brave and beautiful, Mab. And I shan’t ever bring the matter or the man—though he doesn’t deserve the word—up again, unless you wish to discuss it. Mab had grown weak-kneed with relief, reading those words, but she’d still wondered if something would change in the way Francis looked at her. She didn’t think anything had, but how could you tell from twenty-five minutes in a crowded café?

Now they were supposed to have an entire afternoon and night and morning before Mab returned to Bletchley, and Francis was stuck at the office. Mab unloaded every East End curse she knew in a silent scream.

The landlady was still chattering. “. . . pleased as punch to see Mr. Francis marry! Such a fine man, one of my best guests. Do you wish to wait upstairs, dear? ”

“I’ll pop out to see my family first. ”

Lucy greeted Mab’s arrival in Shoreditch with a shout. “I drew a picture! C’n I show you? Mum’s making tea, she’s too busy to look—”

“Beautiful, ” Mab said over the sound of clanking dishes, admiring Lucy’s latest sketch on the back of an old envelope—a horse with a green mane and yellow hooves. Lucy still wanted a pony more than life. “I can’t get you a pony, Luce, but I brought you mounds of paper. You’ll be sketching ponies for months. ”

Lucy gave her a careless kiss and began sorting through the scrap paper Mab had hoarded from Bletchley Park. Lucy was six years old now, lively as a monkey, hair exploding in uncontrollable dark curls. Mab frowned, calling to the kitchen. “Mum, Lucy shouldn’t be running around in skivvies. ” The flat was too stuffy even on a rainy May day to be chilly, but Mab wanted to see Lucy in something better than a grubby vest and knickers.

“You ran around like that till you were eight. ” Mab’s mother came in with the tea mugs, cigarette dangling from the corner of her mouth. “And look how you turned out, Miss Fine and Fancy. ”

Mrs. Churt couldn’t keep a slightly adversarial awe out of her voice whenever she addressed Mab now. Being chauffeured to a fancy London hotel by a Greek prince, getting kitted out in a borrowed silk dress, and watching her Hartnell-clad daughter recite her vows to a gentleman in a Savile Row suit had knocked Mrs. Churt for a loop. “Why couldn’t my other girls turn out like Mabel? ” Mab had heard her mother saying to one of the neighbors. “They settle for dockworkers and factory men, when she nabs herself a dyed-in-the-wool gentleman easy as taking candy from a baby! ”

“Don’t suppose you could spare a few quid? ” she asked now as Mab handed over all her extra clothing coupons for Lucy.

“That’s near a week’s wages, Mum—”

“What, that husband of yours doesn’t give you pin money? ”

Francis had offered, but it seemed greedy when her billet and meals were covered. Mab didn’t want him thinking she was the kind of woman who always had her hand out. “I don’t keep house for him yet, so it’s not necessary. ” Mab pushed a couple of pound notes across the table, then bundled Lucy into her clothes and took her to the park. “Do you want to live in Coventry after the war, Luce? It’s in the very middle of England, and there’s a house there that will be mine, and you could learn to ride. ”

“I don’t want to learn to ride later. I want to learn now. ”

“I don’t blame you. ” Mab took her hand as they crossed Rotten Row. “There are a lot of things I want now, too. But there’s a war on. ”

“Why does everyone say that? ” Lucy said crossly. She probably didn’t remember when there hadn’t been a war on.

Mab headed back to Francis’s digs at twilight, hoping. . . but the landlady shook her head. “He’s not back yet, dearie. Would you like to wait in his room? Normally I’d insist on seeing a marriage certificate before letting any young lady into a gentleman’s quarters under my roof, but Mr. Francis is such a perfect gentleman. . . ”

Not so perfect as that, Mab thought with a certain grin, mounting the carpeted stairs. Francis could, in his quiet way, pen an absolutely indecent letter. Something else she’d learned about him, since the Lake District.

I’m sitting at my desk in my shirtsleeves under a hideous gaslight, smudged in pencil, dreaming of the long map of your body unscrolled across my unmade bed. A map I’ve nowhere near finished charting, though I know a few landmarks well enough to dream on. Your hills and vales, your valleys and mounds, your wicked eyes. You’re an endless serpentine ladder to paradise, and I wish I could coil your hair in my hands and climb you like that great mountain in Nepal where countless explorers have died in ecstasy searching for the peak. I am mixing my metaphors horribly, but longing does that to a man, and you already knew I was a terrible poet. I’d fall back on a better one and pass his work off as my own, except you read far too widely for that to work. “License my roving hands, and let them go, before, behind, between, above, below. . . ” O my Mab, my newfound land! Is John Donne on your list of classic literature? He is probably considered too indecent for females. Certainly he’s no help to a gentleman’s peace of mind either, especially when dreaming of you, my lovely map, my unclimbed ladder. . .

Francis’s room was at the top of the house. Mab let herself in, realizing she had no idea how he lived—for all his letters, he had never once described this place. She looked around the neat, anonymous bedroom, not seeing Francis at all; it was cluttered with the Victorian landlady’s crocheted antimacassars and silk flowers. Nothing here smelled like him, his hair tonic or his shirts or his soap.

Make yourself at home, his note had said. She didn’t want to pry, but she was desperately curious. His bedcovers were pulled taut enough to bounce a shilling—clearly he’d never lost the army habits from the last war. The desk was bare except for pen and blotter and stationery. One photograph in a much-handled frame, facedown on the desk. . . turning it over, Mab saw four young men in uniform. With a stab to her gut like a bayonet thrust, she realized the shortest was Francis, his uniform so big it puddled at his ankles. He stood clutching his weapon with a huge grin, as if he had joined the greatest adventure in the world. The three men around him looked grimmer, their smiles more cynical, or was she reading too much into those blurred, unknown faces? The scribbled date in the corner read April 1918.

“You poor bugger, ” she said softly, touching her husband’s young face. She’d never once seen Francis smile that wide—she wondered if he ever had, since April 1918. There were no names written under any of the men around him. They didn’t live, Mab thought, replacing the picture where she’d found it. I’d stake my life on it.

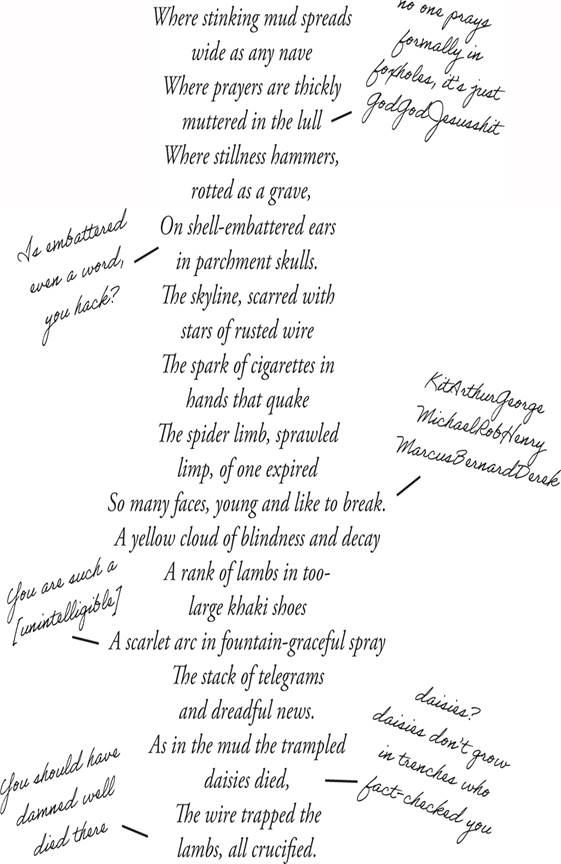

No other photographs, not of his parents, not of Mab. She didn’t have a single picture of herself to send him—she’d have to do something about that—and they hadn’t snapped any wedding photographs. Osla hadn’t been able to find a camera on short notice. Mab went to the bookshelf—no poets, mostly treatises on distant history, long-ago Chinese dynasties and Roman emperors. He seemed to like his reading to take him as far from the twentieth century as possible. At the very back of the shelf, wedged almost out of sight, she found a copy of Mired: Battlefield Verses by Francis Gray, with a copyright page from 1919—it must have been from the first printing run. The spine cracked as if it hadn’t been opened in years, but there were angry scribbles all over the pages, almost every poem marked up. From “Altar, ” his most well-known poem:

Mab laid the book aside, feeling stripped to the core. All the letters he’d written and never a word about any of this. But why would he? No one talked about their war when it was over. If the day ever came that Hitler was defeated and Bletchley Park closed for good, Mab suddenly knew down to her bones that she and everyone else wouldn’t need the Official Secrets Act to tell them to scorch it from their minds. They’d do it anyway. That was what Francis and his surviving friends had done after the last war; it was probably what the Roman and Chinese soldiers in his history books had done after their wars long ago.

In the top drawer of his desk, she found a packet of her letters. She leafed through them, every one clearly much handled, all the way back to the very first note she’d written him after they became engaged—just a few lines suggesting a date he could meet her family. Underneath her signature, he’d scribbled in pencil:

The girl with the hat!

A knock sounded, and Mab jumped out of her skin. Still holding the bunch of letters, she rose to answer.

“Mr. Gray telephoned, dearie. He won’t be able to get away at all tonight—possibly by tomorrow morning. He’s very sorry—some line of questioning he can’t get free of. ”

Mab’s heart sank.

“Would you like some supper? Just mock duck and turnip-top salad, but no one goes away from my table hungry, even with a war on. ”

Mab demurred politely, then shut the door and looked around the little room. It might not have looked like Francis, smelled like him, or carried the shape of him in its shadows, but at that moment she swore she could almost feel him breathing at her shoulder. Before she could lose the feeling, she sat down at his chair and helped herself to his pen and paper.

Dear Francis—sitting in your room without you in it fills me with questions. I know the direction you slant your hat when you cram it over your hair with one hand. I know you take your tea without sugar, even when sugar isn’t rationed. I know you have a ticklish spot at your waist, and I know the song you hum while shaving (“I’m Always Chasing Rainbows”). But sometimes I don’t feel I know you at all. . . and you seem to know me so well.

I wish I had known the boy I saw in the photograph on your desk, the one with a smile that nearly runs round the back of his head. I wish I knew who his friends were. I wish I knew why you called me “the girl in the hat. ”

I wish you were here. —M

Darling Mab—I missed you by eight bloody minutes this morning. I ran all the way home, shamelessly shoving small children into ditches and old ladies into oncoming traffic. Your scent was still lingering when I wrenched the door open. I said a good many words then of which my landlady did not approve. Damn my job, damn the Foreign Office, damn the war.

Don’t regret never getting to know the boy in that photograph. He was an idiot. He’d have been utterly tongue-tied in your presence, and you’d have spent all night talking to his three friends, who would have charmed you. They were all far better men than Private F. C. Gray. (C stands for Charles. Did you know that? It’s entirely possible I never told you. )

As for the girl in the hat, she’s you. Or rather, she’s become you.

I was sixteen, and I’d been in the trenches four months, quite long enough to lose every ideal I’d had. You’ve read the wretched poetry, I won’t repeat anything trite about barbed wire or flying bullets. I had forty-eight hours’ leave coming with my friend Kit—in the photograph, he’s the towhead on the end. The other two had already died, Arthur two weeks before of peritonitis, George three weeks before that of a scrape gone septic. It was just Kit and me left, and he was hauling me to Paris on our next leave. Only he was killed six hours beforehand, gut-shot in a pointless skirmish. I listened to him scream for an hour before a sniper on our own side finally finished him. So I went to Paris on my own.

The Eiffel Tower, the Sacré Coeur. . . I wandered round in an utter daze, looking at all the things we said we’d see, and I don’t remember any of it. A sort of veil had dropped over the whole world, and I stumbled along behind it, peering through the fog. The world had simply gone gray.

There was a hat shop on the Rue de la Paix, and for some reason I stopped in front of it. I wasn’t looking at the hats in the window, I wasn’t looking at anything. I wasn’t thinking anything. But slowly I became aware there was a girl inside, trying on hats.

I don’t remember what she looked like. I know she was tall, and had a pale blue dress. For the Rue de la Paix she looked rather shabby. She’d clearly saved up to buy a hat at this very expensive shop, and by God, she wasn’t going to be sniffed at by any of those coiffed vendeuses. She was scrutinizing those hats like Napolé on inspecting his artillery. Clearly the perfect hat was going to seal her fate in some way, and she was determined to find it. I stood there dumbly, staring through the window as she tried on one after the other, until she found The One. I remember it was pale straw, with a cornflower-blue ribbon round the crown and some wafty sort of netting. She stood before the mirror, smiling, and I realized I was seeing her as if in a bright light—as if she’d stepped out from behind that veil that was bleaching all the color out of the world. A pretty girl in a pretty hat in the middle of an ugly war. I nearly wept. Instead I stood transfixed. I could have watched her forever.

She bought the blue-ribboned hat and came out, swinging her hatbox happily. I didn’t follow her. It wasn’t about trying to find out her name or where she lived. It wasn’t about falling in love with her, whoever she was. It was one bright, beautiful moment in the middle of a hideous world, and when I went back to the trenches, I pulled that moment up and slept on it every night until the war was over. The girl in the hat, in the moment of her joy.

The veil mostly dropped back over me, Mab—it hasn’t ever really gone away. I haven’t seen the world in full color since I was sixteen years old and buried in mud at the front. I came back from that terrible place with all my limbs and most of my sanity, but I can’t say I entirely rejoined the human race. I’ve never been able to shake the feeling of standing in the wings of a play, separated from it by a curtain.

Only sometimes, every now and then, the curtain sweeps back and I see things in full color—I get yanked onto the stage, blinking and dazzled, and I feel.

There was a moment at Bletchley Park during the prime minister’s visit, where you put on your new hat and sang a little song about how a smart hat was a woman’ s cri de coeur. In that moment you became the Girl in the Hat.

I’d enjoyed your company before then, because you were lovely and entertaining. A pleasant companion on a night out, for a man who periodically tries to remind himself that the world has civilized things to offer and not just horrors. But there on the lawn, you dazzled me. You want things so fiercely—you’re so determined to wrest your fate out of the world, horrors be damned, and the odds never seem to daunt you. You will simply put on a smart hat, and conquer the world. And in that moment, I loved you.

I can’t say the veil over my eyes has disappeared simply because you have come into my life. Mostly it’s still there, making it hard for me to reach you. I have spent decades not really trying to reach anyone. But it’s beginning to part more often than it did. When you lift an eyebrow skeptically. When I sink into you and feel you arch against me. When I see you straighten your hat.

Darling Mab, you are and always will be the Girl in the Hat. The girl who makes life worth living.

—F

Mab brought the letter to her evening shift, reading it at the checking machine as she waited for Aggie to halt. She read it three times, then she put it away, hands trembling. Francis didn’t even have to be in the same bed, or the same room, or the same city to give her that feeling of being unshelled, naked as a chick peeled from its egg. She wanted to cry and she wanted to smile, she wanted to dance and she wanted to blush.

Her well-ordered plan for life had always included being married, but had nothing at all about being loved. Because love was for novels, not real life.

And yet. . .

She smiled and read the letter again.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|