- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Principles 6 страница

development model also features services, but focuses on growth and de-velopment by tapping into assets and strengths as it ‘‘meets young people where they are, ’’ building on individual competencies, emphasizing ‘‘pos-itive self identity, ’’ and supporting ‘‘youth/adult partnerships’’ (3). While youth leadership includes many components of youth development, it also ‘‘builds in authentic youth leadership opportunities within programming and organization. ’’ This approach entails young people’s participating in community projects, as they ‘‘deepen historical and cultural understanding of their experiences and community issues’’ and develop skills and capacities for decision-making and problem solving (3). Civic engagement moves youth further into collective empowerment by adding ‘‘political education and awareness, ’’ skills for ‘‘power analysis and action around issues, ’’ the de-velopment of ‘‘collective identity of young people as social change agents, ’’ and involvement in advocacy and negotiation (3). Finally, youth organizing emphasizes the need to build a ‘‘membership base, ’’ which ‘‘engages in di-rect action and mobilizing’’ and also works through alliances and coalitions with other groups. The organizing model includes ‘‘youth as part of [the] core staff and governing body’’ of a grassroots community organization that seeks to alter relations of power and bring about systemic change (3).

Those who subscribe to the youth-led approach, particularly those em-bracing community organizing, have separated themselves from the youth development field, which they consider too apolitical (Innovation Center for Community and Youth Development 2003, 72): ‘‘The reluctance of youth organizing groups to emphasize the youth development aspects of their approach belies the amount of time and resources they committed purely towards supporting the individual development of their core youth orga-nizers. ’’ Advocates of youth-led community organizing have referred to the relationship between this field and youth development as ‘‘two ships pass-ing in the night’’ (Wheeler 2003). These two ships meet on occasions but essentially are using different navigational systems and have different des-tinations. At first glance, they look the same; however, upon closer scrutiny, they are different vessels that sail the same ocean (community).

The Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change (Lawrence et al. 2004) identified the critical nature of structural racism and the need for youth development programs to both acknowledge and address this form of oppression when targeting youth of color. Such a perspective relies heavily on a social and economic justice perspective to help youth better contextualize their experiences. Achieving this goal requires interventions that do not exclusively focus on individual behavior. An asset-driven par-adigm, such as youth development centered on progress toward individual development and achievement outside of a broader community context can-not be expected to achieve lasting and significant change when youth of color and other marginalized young people are the focus of interventions.

A broader social context allows youth to better understand how this nation’s core values, policies, institutions, and practices severely limit youth

| COMMUNITY ORGANIZING AND YOUTH-LED FIELD | |

from achieving their potential, particularly low-income youth of color (Nygreen, Kwon, and Sanchez 2006). Further, a more comprehensive ap-proach enables participating youth to develop an in-depth understanding of how these forces shape their personal destinies, their communities, and the roles they can play in larger arenas. Youniss and colleagues (2002, 13) note:

Youth did not create the post-1989 global uncertainty nor the sprawling global economic structures that can easily breed a sense of impotence. Nonetheless, youth will be the critical participants in the processes that achieve stability, even out the widening gap between rich and poor, preserve the environment, forcibly quell ethnic enmities, and render a balance between globalization and cultural traditions.

The reader may well argue that an asset paradigm, even if focused on individual youth, still is promising. There certainly is an intrinsic value to this approach. However, when youth development programs target youth who confront a litany of social and economic injustices, without systemat-ically addressing those forces, injustices are perpetrated under the guise of helping youth develop their potential! Under such circumstances, youth cannot develop a more sophisticated understanding of the conditions that shape their individual development. Any results achieved and solutions found will fall far short of ultimate success when these larger dimensions are ignored.

Natural values such as personal responsibility, individuality, meritoc-racy, and equal opportunity have different operative meanings, depending on the social profile of the youth being served (Ginwright 2006). Addressing power inequalities is a natural response when injustice is experienced (Cohen 2006; Lawrence et al. 2004). Thus, the embrace of a change agenda for social and economic justice as a central goal or theme separates youth-led com-munity organizing from the more conventional forms of youth develop-ment that emphasize personal growth and positive change within the com-munity (Sherman 2002).

Change can focus on improving services, expanding access, and en-hancing other dimensions that affect the quality of life for youth and their families within existing power structures (Checkoway 2005; Knox et al. 2005). However, justice-based change goals also can seek to alter power relationships in a redistributive manner, even when this may not be the norm or be explicitly stated. Collective action for a safer environment, civic en-gagement, antiracism, gender equality, LGBT rights, peacemaking and con-flict resolution, electoral politics, and education reform all can be con-structed within a framework of youth-led economic and social justice.

Activism connected to themes of social and economic justice is without question one of the most vibrant areas of the youth-led movement, na-tionally and internationally (Brown et al. 2000; Terry and Woonteiler 2000). Social activism is undertaken within an extensive set of public arenas. Each of these arenas, in turn, easily can be subdivided depending upon the focus

52 SETTING THE CONTEXT

and goals of the campaigns. Mullahey, Susskind, and Checkoway (1999, 5) do a splendid job describing youth-led initiatives that have social change as a central focus:

Youth-based initiatives for social change are those in which young people define the issues that they work on and control the organizations through which they work and the strategies they use. In this form, youth employ a variety of strategies, including advocacy, social action, popular education, mass mobilization, and community and program development, to achieve their goals for social change.

According to the Applied Research Center’s survey of youth organizing (Weiss 2003), essentially there are four defined components of youth-led organizing: (1) political analyses and education; (2) arts and culture; (3) per-sonal development; and (4) interpersonal and coalition work. The reader may well argue that these components also can be found in adult-led or-ganizing; however, as will be discussed throughout this book, these com-ponents take on unique and quite prominent manifestations in youth-led community organizing because of historical and social forces.

Youth-led community organizing, unlike most definitions of youth de-velopment, seeks to accomplish a multitude of goals in addition to ad-dressing its primary end of social and economic justice within a community-societal context (Lafferty, Mahoney, and Thombs, 2003). The youth-led movement has managed to combine a variety of youth-focused goals that incorporate academic, social, cultural pride, and service learning objectives (Cervone 2002). This approach effectively embraces a holistic perspective on youth assets and needs, in a fashion similar to how the youth development field has incorporated cognitive, emotional, moral, physical, spiritual, and social core elements.

HoSang (2004, 2) highlights the importance of a holistic perspective in youth-led community organizing:

First, many youth organizing groups have developed an integrated ap-proach to social change, often combining issue-based organizing with leadership development programs, service learning activities, cultural en-richment programs, and even academic and personal support compo-nents. In comparison to adult-based community organizing groups that typically focus on policy outcomes and the organizing skills of its con-stituents, youth groups have crafted a more holistic approach to social change that addresses the many issues young members face.

The use of a community-based service-learning perspective is one prom-ising mechanism for helping youth organizers integrate individual goals with community-focused goals (Camino 2005; Cervone and Cushman 2002; Eyler and Giles 1999). Wheeler (2003) identifies the integration of youth leadership development as an influential step in tying individual youth development to community development in general, with a corresponding

| COMMUNITY ORGANIZING AND YOUTH-LED FIELD | |

validation of the importance of this connection within philanthropic and academic circles.

This holistic perspective opens avenues for rewards, but also raises chal-lenges in creating a ‘‘proper’’ mix of personal and community-focused goals. The ability of youth-led community organizers to achieve both social and individual change will be a key factor in the success of their efforts, in both the short and long term. HoSang (2004) goes on to note that this holistic perspective takes on greater meaning with youth organizers, because social-action campaigns can take a great deal of time before success is achieved. Deriving a series of instrumental and expressive benefits along the way helps ensure that youth reap concrete benefits that can help with immediate needs. Unlike their adult counterparts, youth-led organizing campaigns rarely are affiliated with national organizations or support networks. Con-sequently, they do not enjoy the benefits of training, consultation, and tech-nical support from national organizations, necessitating that their efforts basically create everything from scratch.

Further, these organizing efforts have the advantage of crafting their campaigns with specific local issues in mind and do not have to exert energy and resources responding to national directives. However, lacking the ad-vantages of an infrastructure supported by an external body, youth-led organizing groups invariably have to create local solutions that would benefit from the experiences of other youth-led groups across the nation (HoSang 2004). Youth-led organizing victories, not surprisingly, are re-stricted to small-scale reforms focused on single issues. Lack of collabora-tion across groups, adult as well as youth-led, has precluded focus on broader social issues with national policy implications.

Youth-led community organizing easily can incorporate the elements and goals of decision making, leadership development, skills building, re-lationship building, community service, and identity development, to list a few goals usually associated with youth development (YouthAction 1998). This flexibility, or as critics would say, ‘‘looseness, ’’ allows sponsoring or-ganizations and youth organizers to select a wide range of projects and individual goals for youth organizers. Thus, youth-led community orga-nizing and youth development conceptually can co-exist without severely compromising each other. Youth development is the overarching paradigm, with organizing being the preferred mode or method for achieving the lofty goals inherent in this approach. Nevertheless, as will be discussed later in this book, advocates of youth-led community organizing who embrace a so-cial and economic justice change agenda take issue with this point of view.

Gainwright and James (2002) and other advocates highlight the centrality of political empowerment within a social–political–ecological approach, which effectively transforms youth and their communities. Burgess (2002) grounds youth leadership development within a social-change agenda that ties in youth development, community development, and youth organizing. The emphasis on creating ‘‘social consciousness’’ as an integral part of youth

54 SETTING THE CONTEXT

development leads to a natural tendency for youth to engage in activism as a means of achieving positive individual and community change (LISTEN, Inc., 2003). Mohamed and Wheeler (2001) stress the importance of leader-ship as a vehicle for youth to acquire a range of competencies that will result in their becoming ‘‘engaging’’ citizens. These competencies can entail critical thinking, public speaking, written communication skills, and group facili-tation. As a result, outcomes must encompass both individual and com-munity change to maximize the benefits of youth organizing and youth development for this form of social intervention.

Mokwena and colleagues (1999) advocate the position that youth devel-opment and social change must address two goals: (1) youth participation is a critical segment of positive development; and (2) youth participation ulti-mately must contribute to the development of community and society. The nexus of these two goals helps shape the evolution of youth-led organizing as a vital part of the youth development field. This phenomenon is destined to increase in importance as more youth organizing projects are funded and more scholarship on the subject emerges. Nevertheless, the emergence of an agenda driven by social and economic justice promises to cause consider-able tension in the field of youth development by necessitating a balance between goals for individual growth and those for social change.

Historical Overview of Youth-Led

Community Organizing

As noted above, it would be a serious mistake to ignore the contribution of youth to a number of important organizing efforts in U. S. history (Cohen 2006). In fact, youth activism is as old as this country, having played an influential role in gaining America’s independence, ending slavery, and improving working conditions, as well as gaining civil rights for all (Hoose 1993). Unfortunately, most history books have totally ignored its role in these and other important national events. While the legacy of youth in com-munity organizing can be traced back well over two hundred years, it re-mains largely unappreciated in both organizing and nonorganizing circles. Sadly, this invisibility of youth’s contributions is not restricted to any one era or social campaign, and is due primarily to the inability or unwillingness of adults to recognize assets that youth possess. Furthermore, when history is written, adults invariably are the authors and they tend to view signifi-cant events and circumstances through a narrow, adult-centric lens, failing to recognize the important roles played by young people (HoSang 2005).

Nevertheless, writers such as Hoose (1993) and Gross and Gross (1977) have made an important contribution by highlighting historical examples in which youth took action to help shape their own and others’ destinies. These authors do a wonderful job giving voice to this nation’s youth and

| COMMUNITY ORGANIZING AND YOUTH-LED FIELD | |

explaining their role in creating a better society for all, including its youn-gest members. They have made significant strides toward correcting a pic-ture of history that essentially omitted the significant parts played by youth in creating positive social change.

It is instructive to examine the role and influence of youth in this nation’s civil rights movement, as a case in point. The importance of the civil rights movement in this country is well understood, and social work, probably more than any other profession, owes much to this movement for popu-larizing the practice of community organizing. As already noted, historians have largely ignored the role of youth in this field, even though the birth of the civil rights movement is arguably a watershed in youth organizing (McElroy 2001). Large numbers of youth participated in lunch-counter sit-ins across the South, and college students played an active and influential role in helping to integrate many other segregated settings.

One demonstration had children, primarily elementary-age, march out of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church onto the streets of Birmingham, Ala-bama, on May 2, 1963. So many African-American adults had been arrested that it was difficult for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to replenish their num-bers. Until that point, large numbers of children had not participated in the demonstrations. But children began joining the ranks with adults to help maintain the large size of the protests. Eventually, over six hundred children were arrested. In fact, scenes of children being arrested, being blasted by water from firehoses, and being chased by attack dogs played a crucial role in changing public opinion.

Hoose (1993) argues that young people’s conscience, energy, and cour-age helped shaped American history. Davis (2004), when chronicling the early civil rights movement in Mississippi, notes the central role played by youth (junior and senior high school students) in moving forward a social justice agenda in that state. Civil rights organizer Ed King commented ap-preciatively in 1963 on the contributions of youth to this movement (Davis 2004, 1): ‘‘When nobody else is moving and the students are moving, they are the leadership for everybody. ’’

The experience of one youth activist during Mississippi’s civil rights ac-tions also helps illustrate the point that childhood activism can have a lifelong impact (Open Society Institute 1997, 1–2):

Leroy Johnson wasn’t even in elementary school when his education as an organizer began. Growing up in rural Trouble Grove, Mississippi, his early memories include sitting on his father’s lap at meetings of the Stu-dent Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—SNCC. ‘‘In 1963, I was five years old, and my dad decided that it was time, for me—as the oldest child—to be involved in what was going on in my community. I didn’t understand everything, but the singing, the energy and the spirit in those meetings was the thing that I took with me. ’’ His childhood role as a ‘‘lap activist’’ was the beginning of a lifetime commitment to community organizing. Today, as the Executive Director of Southern Echo, Johnson

56 SETTING THE CONTEXT

integrates young people in all the organizing efforts led by Echo’s mem-bership.

McElroy (2001, 1) makes similar observations and adds another impor-tant perspective:

In history, black leadership positions often have been undertaken by the youngest of society. In these instances, the leadership positions are as-sumed by the children, by those who have not yet been conditioned to feel uncomfortable with second-class citizenship. The youth organizers of past generations have become the adults of this one. Now these leaders are 40 to 50 (years old) and are still forced to undertake the leadership respon-sibilities. The torch must be passed. . . . The key to developing strength in black leadership is to give young people a very strong sense of their own power. The surest path by which to achieve this goal is through education, both conventional and totally unconventional.

Clearly, the involvement of youth by adults in the civil rights movement had immediate and long-term consequences by creating a cadre of future social activists. In fact, the 1960s were an influential period for youth ac-tivism throughout the country. For many, this era represented a critical turn-ing point for youth engagement in political issues across a wide age spec-trum. It should come as no great surprise that some of the leading exponents of youth civil rights, as well as social and economic justice for this group, were heavily involved in social actions during this decade. Spann (2003) and Kreider (2002) describe the many contributions made by youth during this period and show how these acts of civil disobedience changed society.

Hefner (1998) identifies the significance of the 1960s U. S. Supreme Court rulings concerning due process ( juvenile courts) and student rights to wear black armbands to protest the Vietnam War. HoSang (2003) also acknowl-edges the important role youth played in the civil rights movement, and he goes on to examine youth leadership in antiracist movements through such groups as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and the Brown Berets. The term student power emerged to signify the presence of youth as a viable constituency and age group for achieving social change (Kreider 2002). Unfortunately, the faces and voices of youth in these and other social movements have gone largely unnoticed by historians.

Thus, some would argue that youth as a political identity did not emerge until the 1980s and 1990s. Not coincidentally, this period witnessed tre-mendous advances in the use of the media and telecommunications, effec-tively enabling youth to access and create information of particular value and relevance to their lives. It is during this time that the youth-led para-digm clearly began to be incorporated into community organizing that here-tofore had been restricted to including youth to varying degrees. Indeed, this new model put youth in charge. The mission, goals, priorities, agendas, recruitment methodology, leadership, organizational culture, decision-

| COMMUNITY ORGANIZING AND YOUTH-LED FIELD | |

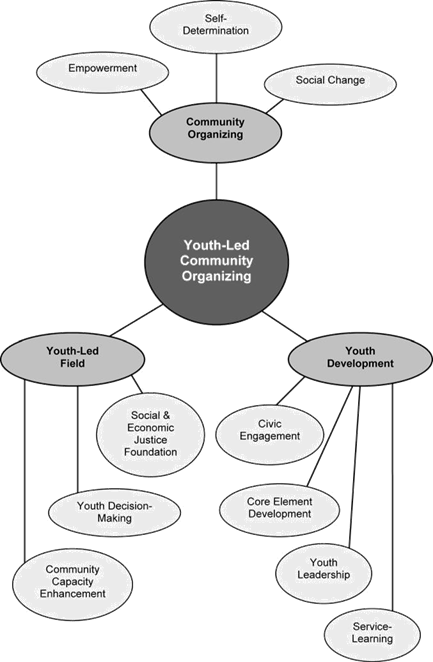

making processes, selection of strategies and tactics, and actions undertaken were all youth-driven and youth-defined. Most important, heavy emphasis was placed on leadership development, which drew on principles of both traditional community organizing and the youth development field. Youth leadership was now at the center of this organizing—which is of, by, for, and about youth, their culture, and their concerns. Figure 3. 1 provides a visual representation of several prominent streams of influence on youth-led community organizing.

YouthAction, based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, is an organization that has a distinguished history of sponsoring youth-led community organizing. This group has identified seven concepts and initiatives that often are in-corporated in youth organizing, but in fact cannot be substituted for youth-led community organizing: (1) leadership development; (2) community services; (3) youth entrepreneurism; (4) civic participation; (5) service to youth; (6) cultural work; and (7) spontaneous high-school walkouts. Each of these forms, although means of achieving worthy goals, lacks a political anal-ysis of social and economic justice and therefore cannot bring about signif-icant changes in power distribution and relationships in this society. Youth-led community organizing enables youth to view their circumstances beyond their local boundaries and helps them better understand and appreciate the magnitude of the social forces that create inequality in the larger society.

For example, issues related to classism, racism, and sexism are quite openly addressed in youth-led community organizing initiatives, because youth bring the consequences of these oppressive forces to their worldview, as well as to the organizations in which they participate (Ginwright 2006; Quiroz-Martinez, HoSang, and Villarosa 2004). Acknowledging and inte-grating these themes into a campaign help ensure that the group’s actions are relevant to larger social conditions. Certainly, there is a natural and strong connection between youth-led community organizing and recogni-tion of neighborhood issues, city and state electoral processes, and national politics (Building Nations 2001). The leap from community building to na-tion building is one of the positive consequences of youth engagement in community organizing and other forms of civic activism and participation. Data from one national youth initiative reinforced the use of community organizing as a method for engaging youth and achieving positive com-munity change (Mohamed and Wheeler 2001).

Youniss and colleagues’ (2002) assessment of youth participation in po-litical and civic arenas led them to conclude that the ‘‘general picture’’ was one of apathy toward conventional politics but active interest in ‘‘non-mainstream’’ civic involvement that leads to mobilization, social action, and youth’s synthesizing of social and economic justice material, individually and collectively. Gauthier (2003) concurs with Youniss and colleagues (2002), and suggests that the concept of political participation be expanded to include involvement in social action and social movements such as anti-globalization demonstrations.

Figure 3. 1. Fields influencing youth-led community organizing.

| COMMUNITY ORGANIZING AND YOUTH-LED FIELD | |

The call for civic action on the part of youth has not been viewed without skepticism and some resistance on the part of youth, for very good reason. This type of activity should not be confused with decision making and social action. Mendel (2004, 31), in quoting Jean Baldwin Grossman, notes:

Grossman, a Princeton University youth scholar, warns that civic action programs are ‘‘harder to pull off than one might think, because often— and the kids smell it really quickly—it’s a pretend. There’s no real cause that’s being served. ‘We’re gonna clean up this park. We’re gonna help this organization by stuffing envelopes. ’. . . The kids know they’re being used. If it was to have a sit-down strike in the mayor’s office, they’d be there with you in a minute. But there’s sort of a backlash amongst a lot of kids against that kind of Mickey Mouse community service. ’’

Grossman’s assessment of the challenges that organizations face in re-cruiting youth highlights the difference when discussing youth as decision makers in community organizing campaigns. Youth-led community orga-nizing, unlike more conventional programs where youth may share deci-sion making with adults and the programming is more on community de-velopment, relies on themes of social and economic justice and strategies oriented toward social change as prime recruiting mechanisms. Youth-led community organizing has continued to broaden its appeal well into the new millennium, as evidenced by the increasing amount of funding and schol-arly literature, as well as the increasing number of workshops and confer-ences highlighting this method (Fletcher 2004; Funders’ Collaboration on Youth Organizing 2003; Pintado-Vertner 2004; Price and Diehl 2004). Youth organizing rightly has taken its place at the nexus of youth-related fields and emerged as a field in its own right. It has provided a viable alternative to youth development programs and activities that focus almost exclusively on individual growth without addressing social justice for all.

This area of practice will continue to inform the fields of youth devel-opment, youth-led, community development, civic engagement, and com-munity organizing while engendering a new generation of youth workers known as youth organizers (Sullivan 2001). The specific designation of youth-led organizing as a field unto itself bodes well for its future. Such catego-rization helps attract the requisite attention (policymakers, academia, and local stakeholders) needed to move the field forward.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|