- Автоматизация

- Антропология

- Археология

- Архитектура

- Биология

- Ботаника

- Бухгалтерия

- Военная наука

- Генетика

- География

- Геология

- Демография

- Деревообработка

- Журналистика

- Зоология

- Изобретательство

- Информатика

- Искусство

- История

- Кинематография

- Компьютеризация

- Косметика

- Кулинария

- Культура

- Лексикология

- Лингвистика

- Литература

- Логика

- Маркетинг

- Математика

- Материаловедение

- Медицина

- Менеджмент

- Металлургия

- Метрология

- Механика

- Музыка

- Науковедение

- Образование

- Охрана Труда

- Педагогика

- Полиграфия

- Политология

- Право

- Предпринимательство

- Приборостроение

- Программирование

- Производство

- Промышленность

- Психология

- Радиосвязь

- Религия

- Риторика

- Социология

- Спорт

- Стандартизация

- Статистика

- Строительство

- Технологии

- Торговля

- Транспорт

- Фармакология

- Физика

- Физиология

- Философия

- Финансы

- Химия

- Хозяйство

- Черчение

- Экология

- Экономика

- Электроника

- Электротехника

- Энергетика

Chapter 5

It was an almost-too-perfect morning. Leaving the pub felt like stepping into one of those heavily retouched photos that come loaded as wallpaper on new computers: streets of artfully decrepit cottages stretched into the distance, giving way to green fields sewn together by meandering rock walls, the whole scene topped by scudding white clouds. But beyond all that, above the houses and fields and sheep doddering around like little puffs of cotton candy, I could see tongues of dense fog licking over the ridge in the distance, where this world ended and the next one began, cold, damp, and sunless.

I walked over the ridge and straight into a rain shower. True to form, I had forgotten my rubber boots, and the path was a rapidly deepening ribbon of mud. But getting a little wet seemed vastly preferable to climbing that hill twice in one morning, so I bent my head against the spitting rain and trudged onward. Soon I passed the shack, dim outlines of sheep huddled inside against the chill, and then the mist-shrouded bog, silent and ghostly. I thought about the twenty-seven-hundred-year-old resident of Cairnholm’s museum and wondered how many more like him these fields held, undiscovered, arrested in death; how many more had given up their lives here, looking for heaven.

By the time I reached the children’s home, what had begun as a drizzle was a full-on downpour. There was no time to dally in the house’s feral yard and reflect upon its malevolent shape—the way the doorless doorway seemed to swallow me as I dove through it, the way the hall’s rain-bloated floorboards gave a little beneath my shoes. I stood wringing water from my shirt and shaking out my hair, and when I was as dry as I was going to get—which was not very—I began to search. For what, I wasn’t sure. A box of letters? My grandfather’s name scribbled on a wall? It all seemed so unlikely.

I roved around peeling up mats of old newspaper and looking under chairs and tables. I imagined uncovering some horrible scene—a tangle of skeletons dressed in fire-blackened rags—but all I found were rooms that had become more outside than inside, character stripped away by moisture and wind and layers of dirt. The ground floor was hopeless. I went back to the staircase, knowing this time I would have to climb it. The only question was, up or down? One strike against going upstairs was its limited options for quick escape (from squatters or ghouls or whatever else my anxious mind could invent) other than hurling myself from an upper-story window. Downstairs had the same problem, and with the added detractor of being dark, and me without a flashlight. So upstairs it was.

The steps protested my weight with a symphony of shudders and creaks, but they held, and what I discovered upstairs—compared to the bombed-out ground floor, at least—was like a time capsule. Arranged along a hallway striped with peeling wallpaper, the rooms were in surprisingly good shape. Though one or two had been invaded by mold where a broken window had let in the rain, the rest were packed with things that seemed only a layer or two of dust away from new: a mildewed shirt tossed casually over the back of a chair, loose change skimming a nightstand. It was easy to believe that everything was just as the children had left it, as if time had stopped the night they died.

I went from room to room, examining their contents like an archaeologist. There were wooden toys moldering in a box; crayons on a windowsill, their colors dulled by the light of ten thousand afternoons; a dollhouse with dolls inside, lifers in an ornate prison. In a modest library, the creep of moisture had bowed the shelves into crooked smiles. I ran my finger along the balding spines, as if considering pulling one out to read. There were classics like Peter Pan and The Secret Garden, histories written by authors forgotten by history, textbooks of Latin and Greek. In the corner were corralled a few old desks. This had been their classroom, I realized, and Miss Peregrine, their teacher.

I tried to open a pair of heavy doors, twisting the handle, but they were swelled shut—so I took a running start and rammed them with my shoulder. They flew open with a rasping shriek and I fell face-first into the next room. As I picked myself up and looked around, I realized that it could only have belonged to Miss Peregrine. It was like a room in Sleeping Beauty’s castle, with cobwebbed candles mounted in wall sconces, a mirrored vanity table topped with crystal bottles, and a giant oak bed. I pictured the last time she’d been here, scrambling out from under the sheets in the middle of the night to the whine of an air-raid siren, rounding up the children, all groggy and grasping for coats on their way downstairs.

Were you scared? I wondered. Did you hear the planes coming?

I began to feel unusual. I imagined I was being watched; that the children were still here, preserved like the bog boy, inside the walls. I could feel them peering at me through cracks and knotholes.

I drifted into the next room. Weak light shone through a window. Petals of powder-blue wallpaper drooped toward a couple of small beds, still clad in dusty sheets. I knew, somehow, that this had been my grandfather’s room.

Why did you send me here? What was it you needed me to see?

Then I noticed something beneath one of the beds and knelt down to look. It was an old suitcase.

Was this yours? Is it what you carried onto the train the last time you saw your mother and father, as your first life was slipping away?

I pulled it out and fumbled with its tattered leather straps. It opened easily—but except for a family of dead beetles, it was empty.

I felt empty, too, and strangely heavy, like the planet was spinning too fast, heating up gravity, pulling me toward the floor. Suddenly exhausted, I sat on the bed—his bed, maybe —and for reasons I can’t quite explain, I stretched out on those filthy sheets and stared at the ceiling.

What did you think about, lying here at night? Did you have nightmares, too?

I began to cry.

When your parents died, did you know it? Could you feel them go?

I cried harder. I didn’t want to, but I couldn’t stop myself.

I couldn’t stop myself, so I thought about all the bad things and I fed it and fed it until I was crying so hard I had to gasp for breath between sobs. I thought about how my great-grandparents had starved to death. I thought about their wasted bodies being fed to incinerators because people they didn’t know hated them. I thought about how the children who lived in this house had been burned up and blown apart because a pilot who didn’t care pushed a button. I thought about how my grandfather’s family had been taken from him, and how because of that my dad grew up feeling like he didn’t have a dad, and now I had acute stress and nightmares and was sitting alone in a falling-down house and crying hot, stupid tears all over my shirt. All because of a seventy-year-old hurt that had somehow been passed down to me like some poisonous heirloom, and monsters I couldn’t fight because they were all dead, beyond killing or punishing or any kind of reckoning. At least my grandfather had been able to join the army and go fight them. What could I do?

When it was over, my head was pounding. I closed my eyes and pushed my knuckles in to stop them from hurting, if only for a moment, and when I finally released the pressure and opened them again, a miraculous change had come over the room: There was a single ray of sun shining through the window. I got up, went to the cracked glass, and saw that it was both raining and shining outside—a bit of meteorological weirdness whose name no one can seem to agree on. My mom, I kid you not, refers to it as “orphans’ tears. ” Then I remembered what Ricky says about it—“the Devil’s beatin’ his wife! ”—and I laughed and felt a little better.

Then, in the patch of quickly fading sun that fell across the room, I noticed something I hadn’t before. It was a trunk—or the edge of one, at least—poking out from under the second bed. I went over and peeled back the bed sheet that hid most of it from view.

It was a big old steamer trunk latched with a giant rusting padlock. It couldn’t possibly be empty, I thought. You don’t lock an empty trunk. Open me! it fairly seemed to cry out. I am full of secrets!

I grabbed it by the sides and pulled. It didn’t move. I pulled again, harder, but it wouldn’t give an inch. I wasn’t sure if it was just that heavy, or if generations of accumulated moisture and dust had somehow fused it to the floor. I stood up and kicked it a few times, which seemed to jar things loose, and then I managed to move it by pulling on one side at a time, shimmying it forward the way you might move a stove or a fridge, until it had come out all the way from under the bed, leaving a trail of parenthetical scars in the floor. I yanked on the padlock, but despite a thick encrustation of rust it seemed rock solid. I briefly considered searching for a key—it had to be here somewhere—but I could’ve wasted hours looking, and the lock was so decayed that I wondered if the key would even work anymore. My only option was to break it.

Looking around for something that might do the job, I found a busted chair in one of the other rooms. I pried off a leg and went to town on the lock, raising the leg over my head like an executioner and bringing it down as hard as I could, over and over, until the leg itself finally broke and I was left holding a splintered stump. I scanned the room for something stronger and quickly spotted a loose railing on the bed frame. After a few stomping kicks, it clattered to the floor. I wedged one end through the lock and pulled the other end backward. Nothing happened.

I hung on it with all my weight, lifting my feet off the floor like I was doing a pull-up with the rail. The trunk creaked a little, but that was it.

I started to get mad. I kicked the trunk and pulled on that rail with every bit of my strength, the veins bulging out of my neck, yelling, Open god damn you, open you stupid trunk! Finally my frustration and anger had an object: If I couldn’t make my dead grandfather give up his secrets, I would damn well pry the secrets out of this old trunk. And then the rail slipped and I crashed to the floor and got the wind knocked out of me.

I lay there and stared at the ceiling, catching my breath. The orphans’ tears had ended and now it was just plain old raining outside, harder than ever. I thought about going back to town for a sledgehammer or a hacksaw—but that would only raise questions I didn’t feel like answering.

Then I had a brilliant idea. If I could find a way to break the trunk, I wouldn’t have to worry about the lock at all. And what force would be stronger than me and my admittedly underdeveloped upper-body muscles wailing on the trunk with random tools? Gravity. I was, after all, on the second floor of the house, and while I didn’t think there was any way I could lift the trunk high enough to get it through a window, the rail along the top of the staircase landing had long ago collapsed. All I had to do was drag the trunk down the hall and push it over. Whether its contents would survive the impact was another issue—but at least I’d find out what was inside.

I hunkered down behind the trunk and began pushing it toward the hall. After a few inches its metal feet dug into the soft floor and it ground stubbornly to a halt. Undeterred, I moved around to the other side, gripped the padlock with both hands and pulled backward. To my great surprise it moved two or three feet in one go. It wasn’t a particularly dignified way of working—this squatting, butt-scooting motion I had to repeat over and over, each slide of the trunk accompanied by an ear-splitting metal-on-wood shriek—but before long I’d gotten it out of the room and was dragging it, foot by foot, doorway by doorway, toward the landing. I lost myself in the echoing rhythm of it, working up a manly lather of sweat in the process.

I finally made it to the landing and, with one final indelicate grunt, pulled the trunk onto it after me. It slid easily now, and after a few more shoves I had it teetering precariously on the edge; one last nudge would be enough to send it over. But I wanted to see it shatter—my reward for all this work—so I got up and carefully shuffled toward the edge until I could glimpse the floor of the gloomy chamber below. Then, holding my breath, I gave the trunk a little tap with my foot.

It hesitated for a moment, wobbling there on the edge of oblivion, and then pitched decisively forward and fell, tumbling end over end in beautiful balletic slow-motion. There came a tremendous echoing crash that seemed to rattle the whole house as a plume of dust shot up at me from below and I had to cover my face and retreat down the hall until it cleared. A minute later I came back and peeked again over the landing and saw not the pile of smashed wood that I had so fondly hoped for, but a jagged trunk-shaped hole in the floorboards. It had fallen straight through into the basement.

I raced downstairs and wriggled up to the edge of the buckled floor on my belly like you would a hole in thin ice. Fifteen feet below, through a haze of dust and darkness, I saw what remained of the trunk. It had shattered like a giant egg, its pieces all mixed up in a heap of debris and smashed floorboards. Scattered throughout were little pieces of paper. It looked like I’d found a box of letters, after all! But then, squinting, I could make out shapes on them—faces, bodies—and that’s when I realized they weren’t letters at all, but photographs. Dozens of them. I got excited—and then just as quickly went cold, because something dreadful occurred to me.

I have to go down there.

* * *

The basement was a meandering complex of rooms so lightless I may as well have explored them blindfolded. I descended the creaking stairs and stood at the bottom for a while, hoping my eyes would eventually adjust, but it was the kind of dark there was no adjusting to. I was also hoping I’d get used to the smell—a strange, acrid stink like the supply closet in a chemistry classroom—but no such luck. So I shuffled in, with my shirt collar pulled up over my nose and my hands held out in front of me, and hoped for the best.

I tripped and nearly fell. Something made of glass went skidding away across the floor. The smell only seemed to get worse. I began to imagine things lurking in the dark ahead of me. Forget monsters and ghosts—what if there was another hole in the floor? They’d never find my body.

Then I realized, in a minor stroke of genius, that by dialing up a menu screen on the cellphone I kept in my pocket (despite being ten miles from the nearest bar of reception), I could make a weak flashlight. I held it out, aiming the screen away from me. It barely penetrated the darkness, so I pointed it at the floor. Cracked flagstone and mouse turds. I aimed it to the side; a faint gleam reflected back.

I took a step closer and swept my phone around. Out of the darkness emerged a wall of shelves lined with glass jars. They were all shapes and sizes, mottled with dust and filled with gelatinous-looking things suspended in cloudy fluid. I thought of the kitchen and the exploded jars of fruits and vegetables I’d found there. Maybe the temperature was more stable down here, and that’s why these had survived.

But then I got closer still, and looked a little harder, and realized they weren’t fruits and vegetables at all, but organs. Brains. Hearts. Lungs. Eyes. All pickled in some kind of home-brewed formaldehyde, which explained the terrific stench. I gagged and stumbled away from them into the dark, simultaneously grossed out and baffled. What kind of place was this? Those jars were something you might expect to find in the basement of a fly-by-night medical school, not a house full of children. If not for all the wonderful things Grandpa Portman had said about this place, I might’ve wondered if Miss Peregrine had rescued the children just to harvest their organs.

When I’d recovered a little, I looked up to see another gleam ahead of me—not a reflection of my phone, but a weak glimmer of daylight. It had to be coming from the hole I’d made. I soldiered on, breathing through my pulled-up shirt and keeping away from the walls and any other ghastly surprises they might’ve harbored.

The gleam led me around a corner and into a small room with part of the ceiling caved in. Daylight streamed through the hole onto a mound of splintered floorboards and broken glass from which rose coils of silty dust, pieces of torn carpet plastered here and there like scraps of desiccated meat. Beneath the debris I could hear the scrabble of tiny feet, some rodentine dark-dweller that had survived the implosion of its world. In the midst of it all lay the demolished trunk, photographs scattered around it like confetti.

I picked my way through the wreckage, high-stepping javelins of wood and planks studded with rusting nails. Kneeling, I began to salvage what I could from the pile. I felt like a rescue worker, plucking faces from the debris, brushing away glass and wood rot. And though part of me wanted to hurry—there was no telling if or when the rest of the floor might collapse on my head—I couldn’t stop myself from studying them.

At first glance, they looked like the kind of pictures you’d find in any old family album. There were shots of people cavorting on beaches and smiling on back porches, vistas from around the island, and lots of kids, posing in singles and pairs, informal snapshots and formal portraits taken in front of backdrops, their subjects clutching dead-eyed dolls, like they’d gone to Glamour Shots in some creepy turn-of-the-century shopping mall. But what I found really creepy wasn’t the zombie dolls or the children’s weird haircuts or how they never, ever seemed to smile, but that the more I studied the pictures, the more familiar they began to seem. They shared a certain nightmarish quality with my grandfather’s old photos, especially the ones he’d kept hidden in the bottom of his cigar box, as if somehow they’d all come from the same batch.

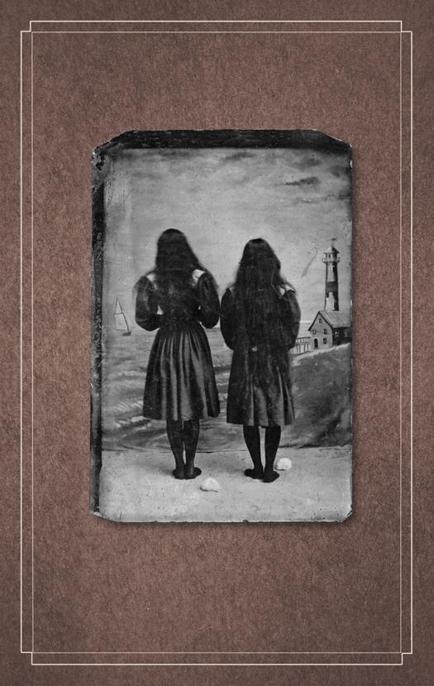

There was, for instance, a photo of two young women posed before a not-terribly-convincing painted backdrop of the ocean. Not so strange in and of itself; the unsettling thing was how they were posed. Both had their backs to the camera. Why would you go to all the trouble and expense of having your picture taken—portraits were pricey back then—and then turn your back on the camera? I half-expected to find another photo in the debris of the same girls facing forward, revealing grinning skulls for faces.

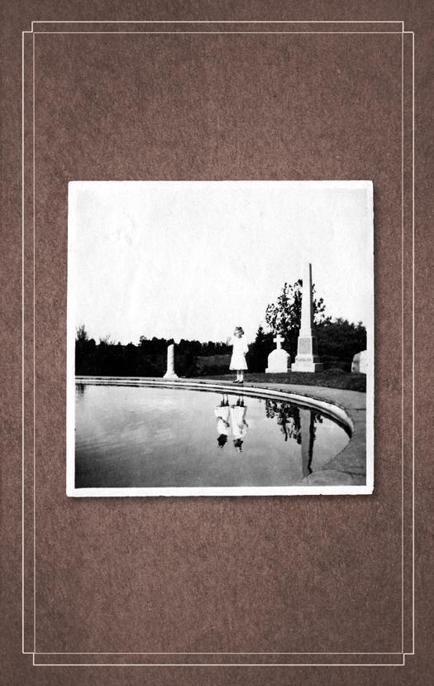

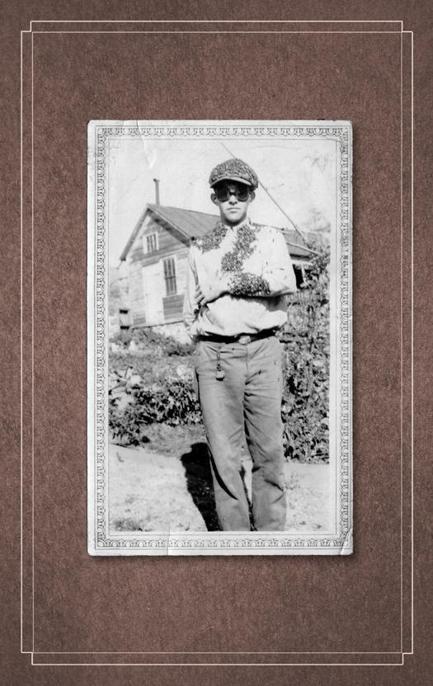

Other pictures seemed manipulated in much the same way as some of my grandfather’s had been. One was of a lone girl in a cemetery staring into a reflecting pool—but two girls were reflected back. It reminded me of Grandpa Portman’s photo of the girl “trapped” in a bottle, only whatever darkroom technique had been used wasn’t nearly as fake-looking. Another was of a disconcertingly calm young man whose upper body appeared to be swarming with bees. That would be easy enough to fake, right? Like my grandfather’s picture of the boy lifting what was certainly a boulder made from plaster. Fake rock—fake bees.

The hairs on the back of my neck stood up as I remembered something Grandpa Portman had said about a boy he’d known here in the children’s home—a boy with bees living inside him. Some would fly out every time he opened his mouth, he had said, but they never stung unless Hugh wanted them to.

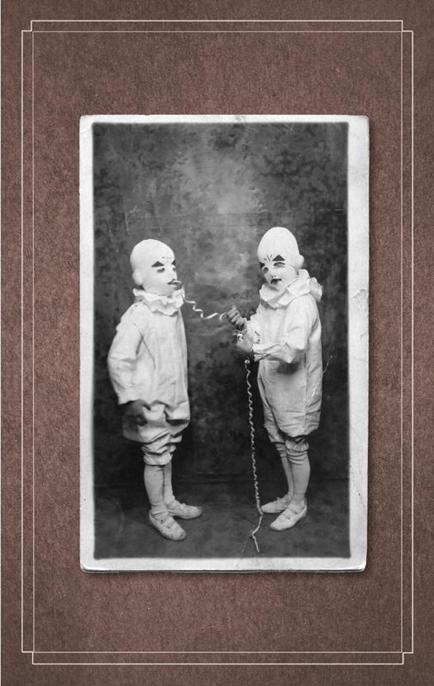

I could think of only one explanation. My grandfather’s pictures had come from the trunk that lay smashed before me. I wasn’t certain, though, until I found a picture of the freaks: two masked ruffle-collared kids who seemed to be feeding each other a coil of ribbon. I didn’t know what they were supposed to be, exactly—besides fuel for nightmares; what were they, sadomasochistic ballerinas? —but there was no doubt in my mind that Grandpa Portman had a picture of these same two boys. I’d seen it in his cigar box just a few months ago.

It couldn’t have been a coincidence, which meant that the photos my grandfather had shown me—that he’d sworn were of children he’d known in this house—had really come from this house. But could that mean, despite the doubts I’d harbored even as an eight-year-old, that the pictures were genuine? What about the fantastic stories that went along with them? That any of them could be true—literally true—seemed unthinkable. And yet, standing there in dusty half-light in that dead house that seemed so alive with ghosts, I thought, maybe …

Suddenly there came a loud crash from somewhere in the house above me, and I startled so badly that all the pictures slipped from my hands.

It’s just the house settling, I told myself—or caving in! But as I bent down to gather the photos, the crash came again, and in an instant what meager light had shone through the hole in the floor faded away, and I found myself squatting in inky darkness.

I heard footsteps, and then voices. I strained to make out what they were saying, but I couldn’t. I didn’t dare move, afraid that the slightest motion would set off a noisy avalanche of debris all around me. I knew that my fear was irrational—it was probably just those dumb rapper kids pulling another prank—but my heart was beating a hundred miles an hour, and some deep animal instinct commanded me to be silent.

My legs began to go numb. As quietly as I could, I shifted my weight from one leg to the other to get the blood flowing again. A tiny piece of something came loose from the pile and rolled away, making a sound that seemed huge in the silence. The voices went quiet. Then a floorboard creaked right over my head and a little shower of plaster dust sprinkled down. Whoever was up there, they knew exactly where I was.

I held my breath.

Then, I heard a girl’s voice say softly, “Abe? Is that you? ”

I thought I’d dreamed it. I waited for the girl to speak again, but for a long moment there was only the sound of rain banking off the roof, like a thousand fingers tapping way off somewhere. Then a lantern glowed to life above me, and I craned my neck to see a half dozen kids kneeling around the craggy jaws of broken floor, peering down.

I recognized them somehow, though I didn’t know where from. They seemed like faces from a half-remembered dream. Where had I seen them before—and how did they know my grandfather’s name?

Then it clicked. Their clothes, strange even for Wales. Their pale unsmiling faces. The pictures strewn before me, staring up at me just as the children stared down. Suddenly I understood.

I’d seen them in the photographs.

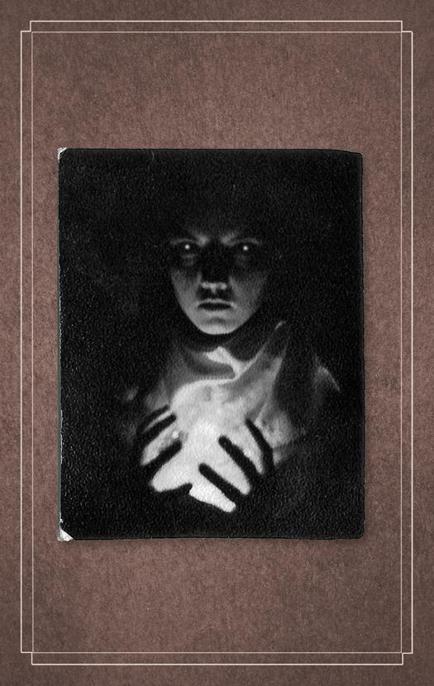

The girl who’d spoken stood up to get a better look at me. In her hands she held a flickering light, which wasn’t a lantern or a candle but seemed to be a ball of raw flame, attended by nothing more than her bare skin. I’d seen her picture not five minutes earlier, and in it she looked much the same as she did now, even cradling the same strange light between her hands.

I’m Jacob, I wanted to say. I’ve been looking for you. But my jaw had come unhinged, and all I could do was stare.

The girl’s expression soured. I was wretched looking, damp from rain and dust-covered and squatting in a mound of debris. Whatever she and the other children had been expecting to find inside this hole in the floor, I was not it.

A murmur passed among them, and they stood up and quickly scattered. Their sudden movement knocked something loose in me and I found my voice again and shouted for them to wait, but they were already pounding the floorboards toward the door. I tripped through the wreckage and stumbled blindly across the stinking basement to the stairs. But by the time I made it back to the ground floor, where the daylight they’d stolen had somehow returned, they had vanished from the house.

I bolted outside and down the crumbling brick steps into the grass, screaming, “Wait! Stop! ” But they were gone. I scanned the yard, the woods, breathing hard, cursing myself.

Something snapped beyond the trees. I wheeled around to look and, through a screen of branches, caught a flash of blurred movement—the hem of a white dress. It was her. I crashed into the woods, sprinting after. She took off running down the path.

I hurdled fallen logs and ducked low branches, chasing her until my lungs burned. She kept trying to lose me, cutting from the path into the trackless forest and back. Finally the woods fell away and we broke into open bogland. I saw my chance. Now she had nowhere to hide—to catch her I had only to pour on the speed—and with me in sneakers and jeans and her in a dress it would be no contest. Just as I started to catch up, though, she made a sudden turn and plunged straight into the bog. I had no choice but to follow.

Running became impossible. The ground couldn’t be trusted: It kept giving way, tripping me into knee-deep bog holes that soaked my pants and sucked at my legs. The girl, though, seemed to know just where to step, and she pulled farther and farther away, finally disappearing into the mist so that I had only her footprints to follow.

After she’d lost me, I kept expecting her prints to veer back toward the path, but they plowed ever-deeper into the bog. Then the mist closed behind me and I couldn’t see the path anymore, and I began to wonder if I’d ever find my way out. I tried calling to her—My name is Jacob Portman! I’m Abe’s grandson! I won’t hurt you! —but the fog and the mud seemed to swallow my voice.

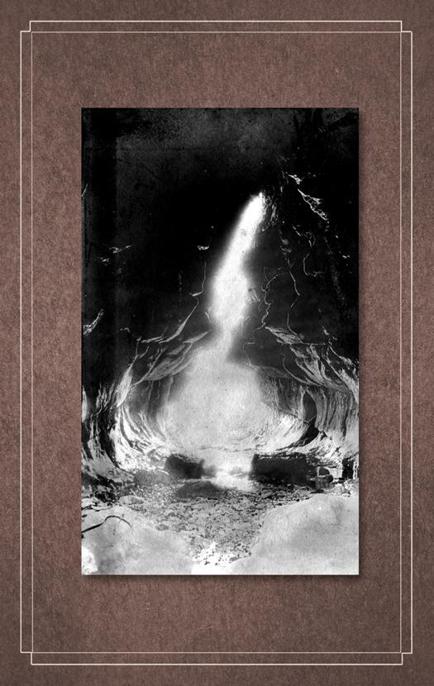

Her footprints led to a mound of stones. It looked like a big gray igloo, but it was a cairn—one of the Neolithic tombs after which Cairnholm was named.

The cairn was a little taller than me, long and narrow with a rectangular opening in one end, like a door, and it rose from the mud on a tussock of grass. Climbing out of the mire onto the relatively solid ground that ringed it, I saw that the opening was the entrance to a tunnel that burrowed deep inside. Intricate loops and spirals had been carved on either side, ancient hieroglyphs the meaning of which had been lost to the ages. Here lies bog boy, I thought. Or, more likely, Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.

But enter I did, because that’s where the girl’s footprints led. Inside, the cairn tunnel was damp and narrow and profoundly dark, so cramped that I could only move forward in a kind of hunchbacked crab-walk. Luckily, enclosed spaces were not one of the many things that scared the hell out of me.

Imagining the girl frightened and trembling somewhere up ahead, I talked to her as I went along, doing my best to reassure her that I meant no harm. My words came slapping back at me in a disorienting echo. Just as my thighs were starting to ache from the bizarre posture I’d been forced to adopt, the tunnel widened into a chamber, pitch black but big enough that I could stand and stretch my arms to either side without touching a wall.

I pulled out my phone and once more pressed it into service as a makeshift flashlight. It didn’t take long to size up the place. It was a simple stone-walled chamber about as large as my bedroom—and it was completely empty. There was no girl to be found.

I was standing there trying to figure out how the hell she’d managed to slip by when something occurred to me—something so obvious that I felt like a fool for having taken this long to realize it. There never was any girl. I’d imagined her, and the rest of them, too. My brain had conjured them up at the very moment I was looking at their pictures. And the sudden, strange darkness that had preceded their arrival? A blackout.

It was impossible, anyway; those kids had all died a lifetime ago. Even if they hadn’t, it was ridiculous to believe they would still look exactly as they had when the photos were taken. Everything had happened so quickly, though, I never had a chance to stop and wonder if I might be chasing a hallucination.

I could already predict Dr. Golan’s explanation: That house is such an emotionally loaded place for you, just being inside was enough to trigger a stress reaction. Yeah, he was a psychobabble-spewing prick. But that didn’t make him wrong.

I turned back, humiliated. Rather than crab-walking, I let go of the last of my dignity and just crawled on my hands and knees toward the gauzy light coming from the mouth of the tunnel. Looking up, I realized I’d seen this view before: in a photograph in Martin’s museum of the place where they’d discovered the bog boy. It was baffling to think that people had once believed this foul-smelling wasteland was a gateway to heaven—and believed it with such conviction that a kid my age was willing to give up his life to get there. What a sad, stupid waste.

I decided then that I wanted to go home. I didn’t care about the photos in the basement, and I was sick of riddles and mysteries and last words. Indulging my grandfather’s obsession with them had made me worse, not better. It was time to let go.

I unfolded myself from the cramped cairn tunnel and stepped outside only to be blinded by light. Shielding my eyes, I squinted through split fingers at a world I hardly recognized. It was the same bog and the same path and the same everything as before, but for the first time since my arrival it was bathed in cheery yellow sunlight, the sky a candy blue, no trace of the twisting fog that, for me, had come to define this part of the island. It was warm, too, more like the dog days of summer than the breezy beginnings of it. God, the weather changes fast around here, I thought.

I slogged back to the path, trying to ignore the skin-crawly feeling of bog-mud gooshing into my socks, and headed for town. Strangely, the path wasn’t muddy at all—as if it had dried out in just a few minutes—but it had been carpet-bombed with so many grapefruit-size animal turds that I couldn’t walk in a straight line. How had I not noticed this earlier? Had I been in some kind of psychotic haze all morning? Was I in one now?

I didn’t look up from the turdy checkerboard that stretched out before me until I’d crossed the ridge and was coming back into town, which is when I realized where all the mess had come from. Where this morning a battalion of tractors had plied the gravel paths, hauling carts loaded with fish and peat-bricks up and down from the harbor, now those carts were being pulled by horses and mules. The clip-clop of hooves had replaced the growl of engines.

Missing, too, was the ever-present buzz of diesel generators. Had the island run out of gas in the few hours I’d been gone? And where had the townspeople been hiding all these big animals?

Also, why was everyone looking at me? Every person I passed stared at me goggle-eyed, stopping whatever they were doing to rubberneck as I walked by. I must look as crazy as I feel, I thought, glancing down to see that I was covered in mud from the waist down and plaster from the waist up, so I ducked my head and walked as fast as I could toward the pub, where at least I could hide in the anonymous gloom until Dad came back for lunch. I decided that when he did, I would tell him straight out that I wanted to go home as soon as possible. If he hesitated, I would admit that I’d been hallucinating, and we’d be on the next ferry, guaranteed.

Inside the Hole were the usual collection of inebriated men bent over foamy pint glasses and the battered tables and dingy decor I’d come to know as my home away from home. But as I headed for the staircase I heard an unfamiliar voice bark, “Where d’ya think yer going? ”

I turned, one foot on the bottom step, to see the bartender looking me up and down. Only it wasn’t Kev, but a scowling bullet-headed man I didn’t recognize. He wore a bartender’s apron and had a bushy unibrow and a caterpillar mustache that made his face look striped.

I might’ve said, I’m going upstairs to pack my suitcase, and if my dad still won’t take me home I’m going to fake a seizure, but instead I answered, “Just up to my room, ” which came out sounding more like a question than a statement of fact.

“That so? ” he said, clapping down the glass he’d been filling. “This look like a hotel to you? ”

Wooden creaks as patrons swiveled around in their stools to get a look at me. I quickly scanned their faces. Not one of them was familiar.

I’m having a psychotic episode, I thought. Right now. This is what a psychotic episode feels like. Only it didn’t feel like anything. I wasn’t seeing lightning bolts or having palm sweats. It was more like the world was going crazy, not me.

I told the bartender that there had obviously been some mistake. “My dad and I have the upstairs rooms, ” I said. “Look, I’ve got the key, ” and I produced it from my pocket as evidence.

“Lemme see that, ” he said, leaning over the counter to snatch it out of my hand. He held it up to the dingy light, eyeing it like a jeweler. “This ain’t our key, ” he growled, then slipped it into his own pocket. “Now tell me what you really want up there—and this time, don’t lie! ”

I felt my face go hot. I’d never been called a liar by a nonrelative adult before. “I told you already. We rented those rooms! Just ask Kev if you don’t believe me! ”

“I don’t know no Kev, and I don’t fancy bein’ fed stories, ” he said coolly. “There ain’t any rooms to let around here, and the only one lives upstairs is me! ”

I looked around, expecting someone to crack a smile, to let me in on the joke. But the men’s faces were like stone.

“He’s American, ” observed a man sporting a prodigious beard. “Army, could be. ”

“Bollocks, ” another one growled. “Look at ’im. He’s practically a fetus! ”

“His mack, though, ” the bearded one said, reaching out to pinch the sleeve of my jacket. “You’d have a helluva time finding that in a shop. Army—gotta be. ”

“Look, ” I said, “I’m not in the army, and I’m not trying to pull anything on you, I swear! I just want to find my dad, get my stuff, and—”

“American, my arse! ” bellowed a fat man. He peeled his considerable girth off a stool to stand between me and the door, toward which I’d been slowly backing. “His accent sounds rubbish to me. I’ll wager he’s a Jerry spy! ”

“I’m not a spy, ” I said weakly. “Just lost. ”

“Got that right, ” he said with a laugh. “I say we get the truth out of ’im the old-fashioned way. With a rope! ”

Drunken shouts of assent. I couldn’t tell if they were being serious or just “taking a piss, ” but I didn’t much care to stick around and find out. One undiluted instinct coursed through the anxious muddle in my brain: Run. It would be a lot easier to figure out what the hell was going on without a roomful of drunks threatening to lynch me. Of course, running away would only convince them of my guilt, but I didn’t care.

I tried to step around the fat man.

He made a grab for me, but slow and drunk is no match for fast and scared shitless. I faked left and then dodged around him to the right. He howled with rage as the rest unglued themselves from barstools to lunge at me, but I slipped through their fingers and ran out the door and into the bright afternoon.

* * *

I charged down the street, my feet pounding divots into the gravel, the angry voices gradually fading behind me. At the first corner I made a skidding turn to escape their line of sight, cutting through a muddy yard, where squawking chickens dove out of my way, and then an open lot, where a line of women stood waiting to pump water from an old well, their heads turning as I flew past. A thought I had no time to entertain flitted through my head—Hey, where’d the Waiting Woman go? —but then I came to a low wall and had to concentrate on vaulting it—plant the hand, lift the feet, swing over. I landed in a busy path where I was nearly run down by a speeding cart. The driver yelled something derogatory about my mother as his horse’s flank brushed my chest, leaving hoof prints and a wheel track just inches from my toes.

I had no idea what was happening. I understood only two things: that I was quite possibly in the midst of losing my mind, and that I needed to get away from people until I could figure out whether or not I actually was. To that end, I dashed into an alley behind two rows of cottages, where it seemed there would be lots of hiding places, and made for the edge of town. I slowed to a fast walk, hoping that a muddy and bedraggled American boy who was not running would attract somewhat less attention than one who was.

My attempt to act normal was not helped by the fact that every little noise or fleeting movement made me jump. I nodded and waved to a woman hanging laundry, but like everyone else she just stared at me. I walked faster.

I heard a strange noise behind me and ducked into an outhouse. As I waited there, hunkering behind the half-closed door, my eyes scanned the graffitied walls.

Dooleys a buggerloving arsehumper.

Wot, no sugar?

Finally, a dog slinked by, trailed by a litter of yapping puppies. I let out my breath and began to relax a little. Collecting my nerves, I stepped back into the alley.

Something grabbed me by the hair. Before I’d even had a chance to cry out, a hand whipped around from behind and pressed something sharp to my throat.

“Scream and I’ll cut you, ” came a voice.

Keeping the blade to my neck, my assailant pushed me against the outhouse wall and stepped around to face me. To my great surprise, it wasn’t one of the men from the pub. It was the girl. She wore a simple white dress and a hard expression, her face strikingly pretty even though she appeared to be giving serious thought to gouging out my windpipe.

“What are you? ” she hissed.

“An—uh—I’m an American, ” I stammered, not quite sure what she was asking. “I’m Jacob. ”

She pressed the knife harder against my throat, her hand shaking. She was scared—which meant she was dangerous. “What were you doing in the house? ” she demanded. “Why are you chasing me? ”

“I just wanted to talk to you! Don’t kill me! ”

She fixed me with a scowl. “Talk to me about what? ”

“About the house—about the people who lived there. ”

“Who sent you here? ”

“My grandfather. His name was Abraham Portman. ”

Her mouth fell open. “That’s a lie! ” she cried, her eyes flashing. “You think I don’t know what you are? I wasn’t born yesterday! Open your eyes—let me see your eyes! ”

“I am! They are! ” I opened my eyes as wide as I could. She stood on tiptoes and stared into them, then stamped her foot and shouted, “No, your real eyes! Those fakes don’t fool me any more than your ridiculous lie about Abe! ”

“It’s not a lie—and these are my eyes! ” She was pushing so hard against my windpipe that it was difficult to breathe. I was glad the knife was dull or she surely would’ve cut me. “Look, I’m not whatever it is you think I am, ” I croaked. “I can prove it! ”

Her hand relaxed a little. “Then prove it, or I’ll water the grass with your blood! ”

“I have something right here. ” I reached into my jacket.

She leapt back and shouted at me to stop, raising her blade so that it hung quivering in the air just between my eyes.

“It’s only a letter! Calm down! ”

She lowered the blade back to my throat, and I slowly drew Miss Peregrine’s letter and photo from my jacket, holding it for her to see. “The letter’s part of the reason I came here. My grandfather gave it to me. It’s from the Bird. That’s what you call your headmistress, isn’t it? ”

“This doesn’t prove anything! ” she said, though she’d hardly glanced at it. “And how do you know so bloody much about us? ”

“I told you, my grandfather—”

She slapped the letter out of my hands. “I don’t want to hear another word of that rubbish! ” Apparently, I’d touched a nerve. She went quiet for a moment, face pinched with frustration, as if she were deciding how best to dispose of my body once she’d followed through on her threats. Before she could decide, though, shouts erupted from the other end of the alley. We turned to see the men from the pub running toward us, armed with wooden clubs and farm implements.

“What this? What’ve you done? ”

“You’re not the only person who wants to kill me! ”

She took the knife from my throat and held it at my side instead, then grabbed me by the collar. “You are now my prisoner. Do exactly as I say or you’ll regret it! ”

I made no argument. I didn’t know if my chances were any better in the hands of this unbalanced girl than with that slavering mob of club-wielding drunks, but at least with her I figured I had a shot at getting some answers.

She shoved me and we were off and running down a connecting alley. Halfway to the end she darted to one side and pulled me after her, both of us ducking under a line of sheets and hopping a chicken-wire fence into the yard of a little cottage.

“In here, ” she whispered and, looking around to make sure we hadn’t been seen, pushed me through a door into a cramped hovel that reeked of peat smoke.

There was no one inside save an old dog asleep on a sofa. He opened one eye to look at us, didn’t think much of what he saw, and went back to sleep. We darted to a window that looked out on the street and flattened ourselves against the wall next to it. We stood there listening, the girl careful to keep a hand on my arm and her knife at my side.

A minute passed. The men’s voices seemed to fade and then return; it was hard to tell where they were. My eyes drifted around the little room. It seemed excessively rustic, even for Cairnholm. Tilting in a corner was a stack of hand-woven baskets. A chair upholstered in burlap stood before a giant coal-fired cooking range cast from iron. Hung on the wall opposite us was a calendar, and though it was too dim to read from where we stood, just looking at it sparked a bizarre thought.

“What year is it? ”

The girl told me to shut up.

“I’m serious, ” I whispered.

She regarded me strangely for a moment. “I don’t know what you’re playing at, but go have a look for yourself, ” she said, pushing me toward the calendar.

The top half was a black-and-white photo of a tropical scene, full-bodied girls with enormous bangs and vintage-looking swimsuits smiling on a beach. Printed above the seam was “September 1940. ” The first and second days of the month had been crossed out.

A detached numbness spread over me. I considered all the strange things I’d seen that morning: the bizarre and sudden change in the weather; the island I thought I’d known, now populated by strangers; how the style of everything around me looked old but the things themselves were new. It could all be explained by the calendar on the wall.

September 3, 1940. But how?

And then one of the last things my grandfather said came to me. On the other side of the old man’s grave. It was something I’d never been able to figure out. There was a time I’d wondered if he’d meant ghosts—that since all the children he’d known here were dead, I’d have to go to the other side of the grave to find them—but that was too poetic. My grandfather was literal minded, not a man who traded in metaphor or suggestion. He’d given me straightforward directions that he simply hadn’t had time to explain: “The Old Man, ” I realized, was what the locals called the bog boy, and his grave was the cairn. And earlier today I had gone inside it and come out someplace else: September third, 1940.

All this occurred to me in the time it took for the room to turn upside down and my knees to go out from under me, and for everything to fade into pulsing, velvety black.

* * *

I awoke on the floor with my hands tied to the cooking range. The girl was pacing nervously and appeared to be having an animated conversation with herself. I kept my eyes most of the way shut and listened.

“He must be a wight, ” she was saying. “Why else would he have been snooping around the old house like a burglar? ”

“I haven’t the slightest idea, ” someone else said, “but neither, it seems, does he. ” So she wasn’t talking to herself, after all—though from where I was lying, I couldn’t see the young man who’d spoken. “You say he didn’t even realize he was in a loop? ”

“See for yourself, ” she said, gesturing toward me. “Can you imagine any relative of Abe’s being so perfectly clueless? ”

“Can you imagine a wight? ” said the young man. I turned my head slightly, scanning the room, but still I didn’t see him.

“I can imagine a wight faking it, ” the girl replied.

The dog, awake now, trotted over and began to lick my face. I squeezed my eyes shut and tried to ignore it, but the tongue bath he gave me was so slobbery and gross that I finally had to sit up just to rescue myself.

“Well, look who’s up! ” the girl said. She clapped her hands, giving me a sarcastic round of applause. “That was quite the performance you gave earlier. I particularly enjoyed the fainting. I’m sure the theater lost a fine actor when you chose to devote yourself instead to murder and cannibalism. ”

I opened my mouth to protest my innocence—and stopped when I noticed a cup floating toward me.

“Have some water, ” the young man said. “Can’t have you dying before we get you back to the headmistress, now can we? ”

His voice seemed to come from the empty air. I reached for the cup, and as my pinky brushed an unseen hand, I nearly dropped it.

“He’s clumsy, ” the young man said.

“You’re invisible, ” I replied dumbly.

“Indeed. Millard Nullings, at your service. ”

“Don’t tell him your name! ” the girl cried.

“And this is Emma, ” he continued. “She’s a bit paranoid, as I’m sure you’ve gathered. ”

Emma glared at him—or at the space I imagined him to occupy—but said nothing. The cup shook in my hand. I began another fumbling attempt to explain myself but was interrupted by angry voices from outside the window.

“Quiet! ” Emma hissed. Millard’s footsteps moved to the window, and the blinds parted an inch.

“What’s happening? ” asked Emma.

“They’re searching the houses, ” he replied. “We can’t stay here much longer. ”

“Well, we can’t very well go out there! ”

“I think perhaps we can, ” he said. “Just to be certain, though, let me consult my book. ” The blinds fell closed again and I saw a small leather-bound notebook rise from a table and crack open in midair. Millard hummed as he flipped the pages. A minute later he snapped the book shut.

“As I suspected! ” he said. “We have only to wait a minute or so and then we can walk straight out the front door. ”

“Are you mad? ” Emma said. “We’ll have every one of those knuckle-draggers on us with brick bats! ”

“Not if we’re less interesting than what’s about to happen, ” he replied. “I assure you, this is the best opportunity we’ll have for hours. ”

I was untied from the range and led to the door, where we crouched, waiting. Then came a noise from outside even louder than the men’s shouting: engines. Dozens, by the sound of it.

“Oh! Millard, that’s brilliant! ” cried Emma.

He sniffed. “And you said my studies were a waste of time. ”

Emma put her hand on the doorknob and then turned to me. “Take my arm. Don’t run. Act like nothing’s the matter. ” She put away her knife but assured me that if I tried to escape I’d see it again—just before she killed me with it.

“How do I know you won’t anyway? ”

She thought for a moment. “You don’t. ” And then she pushed open the door.

* * *

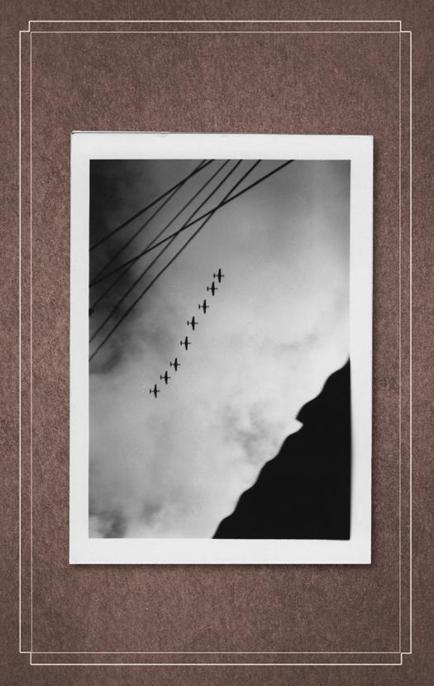

The street outside was thronged with people, not only the men from the pub, whom I spotted immediately just down the block, but grim-faced shopkeepers and women and cart drivers who’d stopped what they were doing to stand in the middle of the road and crane their heads toward the sky. There, not far overhead, a squadron of Nazi fighter planes was roaring by in perfect formation. I’d seen photos of planes like these at Martin’s museum, in a display titled “Cairnholm under Siege. ” How strange it must be, I thought, to find yourself, in the midst of an otherwise unremarkable afternoon, suddenly in the shadow of enemy death machines that could rain fire down upon you at a moment’s notice.

We crossed the street as casually as possible, Emma clutching my arm in a death grip. We nearly made it to the alley on the other side before someone finally noticed us. I heard a shout and we turned to see the men start after us.

We ran. The alley was narrow and lined with stables. We’d covered half its length when I heard Millard say, “I’ll hang back and trip them up! Meet me behind the pub in precisely five and a half minutes! ”

His footsteps fell away behind us, and when we’d reached the end of the alley Emma stopped me. We looked back to see a length of rope uncoil itself and float across the gravel at ankle height. It pulled taut just as the mob reached it, and they went sprawling over it and into the mud, a tangled heap of flailing limbs. Emma let out a cheer, and I was almost certain I could hear Millard laughing.

We ran on. I didn’t know why Emma had agreed to meet Millard at the Priest Hole, since it was in the direction of the harbor, not the house. But since I also couldn’t explain how Millard had known exactly when those planes were going to fly over, I didn’t bother asking. I was even more baffled when, instead of sneaking around the back, any hope of our passing undetected was dashed by Emma pushing me right through the front door.

There was no one inside but the bartender. I turned and hid my face.

“Barman! ” Emma said. “When’s the tap open round here? I’m thirsty as a bloody mermaid! ”

He laughed. “I ain’t in the custom of servin’ little girls. ”

“Never mind that! ” she cried, slapping her hand on the bar. “Pour me a quadruple dram of your finest cask-strength whiskey. And none of that frightful watered-down piss you generally serve! ”

I began to get the feeling she was just messing around—taking the piss, I should say—trying to one-up Millard and his rope-across-the-alley trick.

The bartender leaned across the bar. “So it’s the hard stuff yer wantin’, is it? ” he said, grinning lecherously. “Just don’t let your mum and dad hear, or I’ll have the priest and constable after me both. ” He fetched a bottle of something dark and evil looking and began pouring her a tumbler full. “What about your friend, here? Drunk as a deacon already, I suppose? ”

I pretended to study the fireplace.

“Shy one, ain’t he? ” said the barman. “Where’s he from? ”

“Says he’s from the future, ” Emma replied. “I say he’s mad as a box of weasels. ”

A strange look came over the bartender’s face. “Says he’s what? ” he asked. And then he must’ve recognized me because he gave a shout, slammed down the whiskey bottle, and began to scramble toward me.

I was poised to run, but before the bartender could even get out from behind the bar Emma had upended the drink he’d poured her, spilling brown liquor everywhere. Then she did something amazing. She held her hand palm-side down just above the alcohol-soaked bar, and a moment later a wall of foot-high flames erupted.

The bartender howled and began beating at the wall of fire with his towel.

“This way, prisoner! ” Emma announced, and, hooking my arm, she pulled me toward the fireplace. “Now give me a hand! Pry and lift! ”

She knelt and wedged her fingers into a crack that ran along the floor. I jammed my fingers in beside hers, and together we lifted a small section, revealing a hole about the width of my shoulders: the priest hole. As smoke filled the room and the bartender struggled to put out the flames, we lowered ourselves down one after another and disappeared.

The priest hole was little more than a shaft that dropped about four feet to a crawl space. It was pure black down there, but the next thing I knew it was filled with soft orange light. Emma had made a torch of her hand, a tiny ball of flame that seemed to hover just above her palm. I gaped at it, all else forgotten.

“Move it! ” she barked, giving me a shove. “There’s a door up ahead. ”

I shuffled forward until the crawl space came to a dead end. Then Emma pushed past me, sat down on her butt, and kicked the wall with both heels. It fell open into daylight.

“There you are, ” I heard Millard say as we crawled into an alley. “Can’t resist a spectacle, can you? ”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, ” replied Emma, though I could tell she was pleased with herself.

Millard led us to a horse-drawn wagon that seemed to be waiting just for us. We crawled into the back, stowing away beneath a tarpaulin. In what seemed like no time, a man walked up and climbed onto the horse, flicked its reins, and we lurched into juddering motion.

We rode in silence for a while. I could tell from the changing noises around us that we were headed out of town.

I worked up the courage to ask a question. “How’d you know about the wagon? And the planes? Are you psychic or something? ”

Emma snickered. “Hardly. ”

“Because it all happened yesterday, ” Millard answered, “and the day before that. Isn’t that how things go in your loop? ”

“My what? ”

“He isn’t from any loop, ” Emma said, keeping her voice low. “I keep telling you—he’s a damned wight. ”

“I think not. A wight never would’ve let you take him alive. ”

“See, ” I whispered. “I’m not a whatever-you-said. I’m Jacob. ”

“We’ll just see about that. Now keep quiet. ” And she reached up and peeled back the tarpaulin a little, revealing a blue stripe of shifting sky.

|

|

|

© helpiks.su При использовании или копировании материалов прямая ссылка на сайт обязательна.

|